CONTENTS

LINKING THE NETWORK INTO THE WIDER LOCAL COMMUNITY

LACEWEB AND FUNCTIONAL MATRICES

THE LACEWEB AS A SOCIAL MOVEMENT

COMPARING LACEWEB AND NEW LATIN AMERICAN SOCIAL

MOVEMENTS

A MODEL FOR A 200 YEAR TRANSITION TO A HUMANE CARING EPOCH

WRITING BY OTHERS ABOUT WORLD ORDER TRANSITIONS

EXAMPLES OF RECENT LACEWEB ACTION

INDIGENOUS GLOBAL HUMANE DISCOURSE AND CONSCIOUSNESS RAISING

DIAGRAMS

Diagram 1 The Growth Curve of any System

PHOTOS

Photo 1 Tailings from Bougainville’s Panguna Mine

fills the valley with toxic sludge.

Photo 2 Spontaneous Dance as Change Process

SOCIOGRAMS

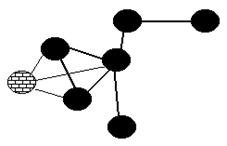

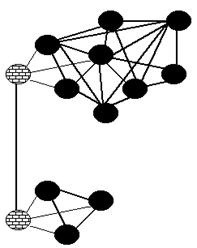

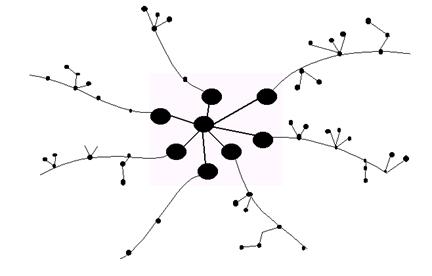

Sociogram 26

- Integrated network (above) Dispersed network (below)

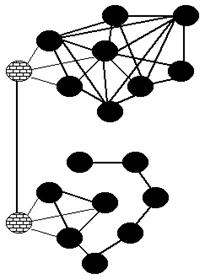

Sociogram 32 - Rumors network linking very small

healing groups at different

locations

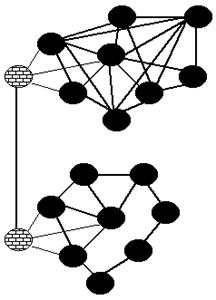

Sociogram 33 - A dispersed network with a nodal

link person in the middle

ORIENTING

This, the

final Chapter commences with a sociogram based discussion of some of the

structures and processes associated with evolving, enabling, and supporting

Laceweb networks and the passing on of nurturing ways. A big picture overview

is then made including a comparison between Laceweb and new forms of Latin

American Social Movements. The Chapter then explores more of Neville’s own

writings about his macro-framework for the next 200 years. The Chapter

concludes with evolving action and future possibilities for the Laceweb Social

Movement.

FIGURES DEPICTING THE EVOLVING OF

INDIGENOUS/SMALL MINORITY HEALING NETWORKS IN SE ASIA OCEANIA AUSTRALASIA

REGION

This section uses qualitative

sociogram based research to map and encapsulate the transfer of

micro-experiences, understandings and healings within Laceweb networks. This

sociogram research draws upon my prolonged deep interviews with Neville along

with my action research (some of it jointly with Neville) in Laceweb contexts

from 1988 onwards. When I showed Neville that I was using sociograms in my

mapping and modeling of Laceweb process in 1993, Neville was delighted and drew

my attention to the Fraser House sociogram research into the friendship patterns among staff and patients in Fraser

house (Clark and Yeomans 1969).

As stated in other parts of this

Thesis, the processes outlined below are pervasively tentative. In much of

mainstream Western service based action, predictability and certainty is deemed

a requirement (Davis and Meyer 1999; Pascale,

Millemann et al. 2000). Laceweb tentativeness re-cognizes

the natural self-organizing nature of local action. Everything depends on local

healers. Nothing may happen unless

local healers want it. This is why

tentative language is used in describing linkings and exchange. Even in giving

examples it is understood that everything is cast as possibilities. Typically,

wellbeing enablers and natural nurturers are present among local Indigenous and

small minority communities. Both

Laceweb enablers or local Indigenous, small minority and other

intercultural people may identify local wellbeing nurturers and local enablers.

Locals seeking well-being support tend to use these local nurturers. Typically,

these local nurturers are ‘self starters’. The black disk symbol Sociogram 1 is

used to depict a local Indigenous, small minority or intercultural wellbeing

nurturer.

It is understood that these nurturers

are always living among other locals depicted as in sociograms 2

![]()

The crosshatched disk symbol

(Sociogram 3) is used to depict a non-local Laceweb enabler. Enablers, as their

name implies, enable others to help themselves towards wellbeing. Enablers may

share micro-experiences of healing ways and peacehealing that other Indigenous,

small minority or intercultural nurturers have found to work. Learning is

typically by personally experiencing using the healing way on self and others –

embodying.

The darker crosshatched disk symbol

(Sociogram.4) is used to depict a local Laceweb enabler

Typically, co-learning takes place. That is, as a person shares embodying

healing ways with others, the sharer also

receives insights and understandings back from these recipients; hence,

lines in the sociograms (as in Sociogram 5) represent a two-way flow of healing sharings. Typically what flows between

people are rumors – rumors of what works. Typically the ‘author’ of the rumor

is not disclosed. It does not matter.

The darker line between two locals in

Sociogram 5 represents a two-way flow

of healing sharings and that these sharings have been adapted to local healing ways. That is, non-local

enablers may share with locals many of the micro-experiences that they have

received from other places and cultures. The local may adapt these

micro-experiences to the local healing ways. They may then pass these

‘localized’ healings on to other locals.

Sociogram 6 depicts a non-local

enabler sharing healing ways with three local natural nurturers. The lighter line

depicts transfer between cultures. In this example, let’s assume

different micro-experiences are passed on to each of the three local natural

nurturers.

Let us say the three locals in

Sociogram 6 each receive 3 healing ways from the enabler. They then adapt them

to local healing ways. Sociogram 7

depicts these three locals then passing these micro-experiences on to each

other.

In this example, each local receives

six healing ways via other locals - that is, three from each of the other two

locals. They each receive three healing ways directly from the enabler. That

is, they are receiving more from locals

than from the enabler. Of course, each of these ways was first passed on by the

enabler. This process means that locals are receiving twice as much via other

locals and these other sharings are adapted to local way. Locals become the primary source for shared ways. The

enabler is in the background.

The

Sharing of Micro-experiences Among Locals - a Summary

The following Figure 1 lists Cultural

Keyline aspects of Laceweb action:

·

Locals

adapt micro-experiences to local nurturing ways.

·

Locals

pass on their new skills to each other.

·

In

this way locals become a resource to each other.

·

No

local becomes a ‘font of all wisdom’.

·

Locals

may begin to take on the enabler role.

·

Enablers

are not seen as the ‘font of all wisdom’ either.

·

As

the local healing network strengthens, the enabler becomes even more invisible.

·

Locals

take on or extend their local enabler roles

·

Locals

use naturalistic inquiry and iterative action research

·

Nurturing

takes place as people go about their everyday life

·

The

sharings are self-organizing

·

No

one is ‘in charge’, although everyone has a say

·

Shared

accountability for unfolding action

·

Global

multidirectional communicating and co-learning.

·

Sharing

micro-experiences and the healing/nurturing role

·

Nurturing

is an intrinsic aspect of cultural locality

·

Enacting

of local wisdoms about ‘what works’.

·

What

‘fits’ may be repeated, shared and consensually validated

·

Healing

actions are resonant with traditional Indigenous ways

·

The

use of organic processes - the survival of the fitting

·

Knowing

includes the ever tentative unfolding action

·

Organic

roles - orchestrating, enabling and the like

·

Healing

actions that work may be passed on as rumors that may be validated by action

Figure 1 Cultural Keyline Aspects of Laceweb

Action

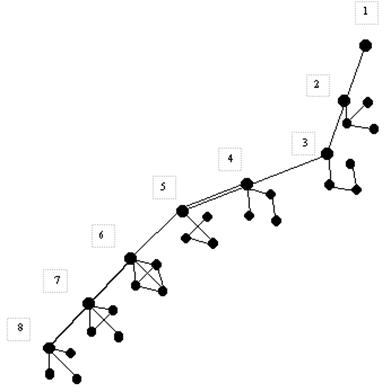

Sociogram 8 depicts one of the three

locals linking and sharing with two other local natural nurturers.

Sociograms 9, 10 and 11 depict the

progressive building up of a chain of linked people with sharings going back

and forth along the chain. This is isomorphic with what Neville was doing in

Mackay and Townsville, and in a more sustained form in the Atherton Tablelands

Region inland from Cairns as well as in the Darwin Top end. Recall that Neville

said that he had learnings from those with whom he passed on healing ways -

co-learnings (Yeomans 1990).

Sociogram 10

Sociogram 11

In time, more and more skills are

generated in the healing network and passed on to others. The role of enabler

continues to become more invisible.

In Sociograms 12 and 13 the local who

commenced the chain makes links firstly with the second and then the fourth

person in the chain. This may have the effect of enriching the speed, flow and

feedback of healing ways micro-experience. Note also that in Sociogram 13 a

link has also been made between one of the original three locals and the new

local not in the chain. The healing network is beginning to expand in mutual

support.

Sociogram 12

Sociogram 13

Further links have been made in

Sociogram 14 so that now, the local that started the chain is directly linked

to every member of the chain. The chain is also linked into the original three

via the other new member. Notice that the enabler’s links to the three continue

with the lighter links signifying that the micro-experiences the enabler is

sharing originate outside the local culture. The enabler is in a two-way

co-mentoring/co-learning flow and is receiving feedback from the three locals about

how the healing ways they are receiving from the enabler are being adapted

locally.

Sociogram 14

Sociogram 15

In Sociogram 15, the fourth person in

the chain has linked with the first and second person in the chain.

These further links may have the

potential to:

·

increase

and strengthen the diversity in healing ways as people share their differing

capacities

·

increase

the intrinsic bonding within the network

·

increase

the availability of potential support

·

increase

the store of micro-experience in the network

·

increase

the potential for self organizing in the network

·

increase

the potential for emergence in the network

In Sociogram 16 the natural nurturer

who has been evolving the network is depicted as evolving into a local enabler.

This enabler role emerges over time. Further linkings have been made. The

expanding network has potential for both unifying experience and enrichment

through diversity.

Sociogram 16

Now the ‘web’ like structure of the

linkings is emerging. Another term for this is ‘functional matrix’. Recall that

the word ‘matrix’ is from the Greek word having the following meanings:

·

the

womb

·

place

of nurturing

·

a

place where anything is generated or developed

·

the

formative part from which a structure is produced

·

intercellular

substance

·

a

mold

·

type

or die in which anything is cast or shaped

·

a

multidimensional network

Latest findings in neuro-biology hint

that there is a massive information carrying capacity in the cytoskeleton – the

very material that makes up cell walls in the human body. Similarly these

Laceweb webworks are vibrant experience exchange networks and an extension of

the connexity work Neville did at the psychobiological – psychosocial interface

in Fraser House.

When Neville got started in Mackay,

Townsville, Cairns, the Atherton Tablelands and around Darwin, Neville was the

one initiating almost all of the linking. He said that this was a very slow

process. In these examples the enabler has only made links with the original

three locals. It may be that further

links are made between the enabler and others in the network. It is not however necessary. In some contexts

the links between locals may increase ahead of the links between locals and

non-local enablers.

It will be noted that by Sociogram 16,

the outside enabler may have become a relatively invisible figure. This may be

the experience in SE Asia and Oceania contexts. The non-local enabler may

continue to share micro-experiences with the original locals. By now most of

the healing ways may be received from locals.

In the contexts that Neville energized

in the Australian Far North most of the natural nurturers had a close connexion

to Neville.

Healing micro-experiences may be

combined and adapted as appropriate to people, place and context. Over 30 years

of experience has demonstrated that these processes may be self-enriching.

People may be intuitively innovative. The local ‘seed-bank’ of healing stories

is soon replanted and bearing fruit.

Sociogram 17

To go back in time, while the local

network depicted in the preceding series of sociograms has been emerging, the

enabler may have been enabling, supporting, mentoring/co-mentoring and linking

with one or more other enablers who are in turn linking with other locals not

known to the local network mentioned above.

Sociogram 18 depicts such a linking.

While this second enabler is also linking with three locals, it may be any

small number. Typically, these linkings start out small.

Sociogram 18

Sociogram 19 to 24 depict the evolving

of this second network. The sequence may differ, though many of the

characteristics of the first network emerge. Linked chains of people may

emerge. Further linking strengthens the number of people available to each

other for mutual sharing and support.

Sociogram 19

Sociogram 20

Sociogram 21

Sociogram 22

Sociogram 23

Sociogram 24

Sociogram 25 depicts later links being

made between the two local networks and the local enabler in the first network

links the two local networks. As these links are extended, the two networks may

merge to be one expanded network.

Sociogram 25

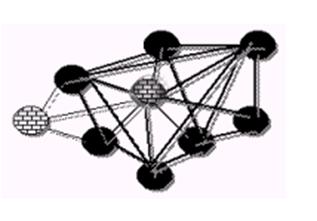

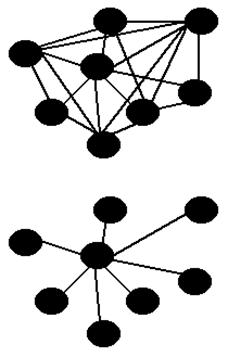

There is always the possibility that

local healers may position themselves such that they generate links to other

local healers without linking the locals to each other. In this way any local

doing this may become the one all the others rely on. Sociogram 26 shows the

original network of eight locals and underneath, another eight locals where

seven locals only have one link and that link is with the local in the center.

A moments reflection may give a feel for the difference between the original

network and this later form of linking, what has been described as integrated

and dispersed networks (Cutler 1984, p. 253-266).

Sociogram 26

- Integrated network (above) Dispersed network (below)

This second pattern may spread healing

ways. This second pattern (the dispersed network with a nodal person in the

middle linking rumor lines is prevalent throughout the Laceweb in SE Asia where

the safety and integrity of the natural nurturers is under threat. This is

discussed later.

Experience has shown that the

integrated network with the multiple cross linkings has many advantages such

as:

·

Members

have multiple people to call on for support

·

The

flow of information tends to be faster and richer

·

The

diversity enriches the micro-experiences being shared

·

It

is possible to get cross-checks on others’ outcomes

LINKING THE NETWORK INTO THE WIDER

LOCAL COMMUNITY

So far we have only depicted the links

between enablers (non-local and local) and local healers and nurturers.

Typically, these local natural nurturers are regularly being approached by

local friends and family for nurturing. Sociogram 27 depicts three other locals

(shown as the striated circles) that have links with one of the healers.

Typically, each of the healers has a number of locals that seek out their

support from time to time. As healers pass on healing ways to locals that

enable them to help themselves, often these other locals emerge as healers and

start to merge with the wider healing network.

Sociogram 27

THE ENABLING

NETWORK

Enablers are also part of an enabling

network. Sociogram 28 depicts the original enabler’s links to the Laceweb

enabler network.

Sociogram 28

After a time, the network may start to

link more widely into the wider local community and extend through a number of

surrounding villages (settlements/towns) with links to more distant places. The

healing network starts to enable self-healing among the local communities. More

and more people discover that they can change their wellbeing as depicted in

Sociogram 29. Nurturers begin to

identify other nurturers living in their area with whom they have not yet

established links.

Sociogram 29

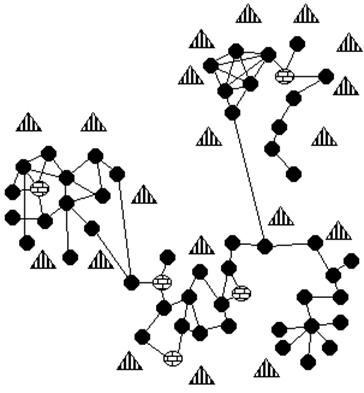

After a time, whole villages

(settlements/towns) may enter cultural healing action as depicted in Sociogram 30. The triangular symbol represents a

dwelling and the three rings of dwellings depict three villages located in

reasonable close walking distance from each other. After conversations in

Cairns with a Bougainvillian living in Bougainville during the Bougainville

Conflict, he said that how I described Laceweb action was very resonant with

Bougainville local ways, and that when he went back he would keep and eye open

for the natural nurturers. A few months later I received a message through a

Bougainville person, Alex Dawia from this person. The message was, ‘The

nurturer women networks are alive and well in the hills around Arawa. in

Bougainville’.

Sociogram 30

Note the differing patterns of

transfer depicted in Sociogram 30.

At

the top right:

·

an

integrated support network

·

an

isolated link

·

a

dispersed chain linking 5 people

At

bottom right:

·

one

nodal person is a source for five separate others in a dispersed network

After a time, locals may evolve as

enablers and so further assist in the spreading of cultural healing action

At other times there may be campout

festivals, celebrations, and gatherings of enablers, nurturers and other locals

from a number of villages (settlements/towns). These may last for days with

diverse and spontaneous cultural healing action occurring. An example of this

was the Small Island Coastal and Estuarine People Gathering Celebration in 1994

(Roberts and Widders 1994). Note that it called a ‘Gathering

Celebration’. Sociogram 31 depicts the network shown in Sociogram 30 after they

have gathered together in a healing festival (healfest). Typically such

gatherings create opportunities for a sudden large increase in linking. You may

note that the people in the lower right who had relied on the central person

have now met up with each other and formed into a mutually supporting net and

that this net has linked with the enabler to their left and into that little

network. The network on the upper left has also made further linkings and one

person has made many linkings throughout the other networks. All of this

linking may hold forth promise for further enriching.

. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sociogram 31

All of the

foregoing depicts

the forms of networks Neville was evolving in the Australia Top End. Sometimes

an intercultural enabler may set up links with healers who do not want

information about themselves, their links, or their Laceweb involvement known

to anyone else. This is because healing in some contexts may be a very

subversive activity – for example, during the decades that Indonesia had

control of East Timor, militia were systematically used to terrorize and

traumatize the local population for social control. possibly killing around

150,000 people out of a population of approximately 700,000 (Mares 2001). In this context, healing becomes a

subversive activity and hence healers may be at high risk and specifically

targeted for elimination.

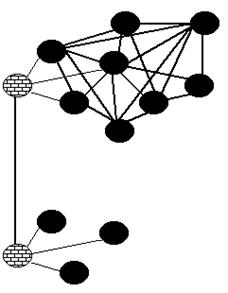

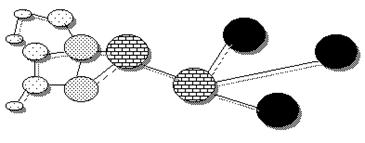

An enabler may set up links with a

number of these ‘anonymous’ healers. Each of these may have ‘trust’ links with

between one or as many as four or five people along ‘rumor lines’. Sociogram 32

depicts such a rumor line where each of the link-people has a small group of

healers they know in their local area. Each of these sets of other local

healers is not known to any of the others in the rumor line.

Sociogram 32 - Rumors network linking very small

healing groups at different locations

Considerable portions of the Laceweb

throughout the SE Asia Oceania Region take this form. The larger black circles

depict the healing people who pass on the healing rumors backwards and forwards

to healers in other localities. There

are small groups of healers in the different locations. Number 1 is a nodal

person with links to other parts of the Laceweb as shown in Sociogram 33.

Number 1 knows 2, 3, 4 and 5. Numbers 4, 5 and 6 know each other. Numbers 6, 7

and 8 know each other. Typically, no one knows more than 4 or 5 people in the

chain. In the Laceweb there can be very long chains where healers know only

between two and five people in the chain. In this respect the network is very

similar to neural networks. Also like the brain, information may travel very

quickly.

Note that the small groups at

different locations may have different forms of linking with each other. It is

possible that these little local networks may extend as per the processes

outlined earlier in this section. At any point in the chain and from any person

in the local small network, rumors can be passed on to natural nurturers in

other localities and hence the network spreads.

Sociogram 33 - A dispersed network with a nodal

link person in the middle

The healer in the middle in Sociogram

33 is a nodal person and a key energizer in passing rumors from one segment of

a network into many other rumor lines linking local small networks. Often a

nodal person is able to pass on the healing ways from one cultural rumor line

into the rumor line of another culture. Any of the little local networks may

have potential to expand in the local area by locating other natural nurturers

or by so enriching others in their self-healing that they also become enablers

and natural nurturers. The above sociogram is idealized in the linear nature of

some of the lines. This was only for ease of drawing. In practice, the links

jump between different places in the region and a healing rumor may start in

the Southern part of Siberia, pass to the Deccan Plateau in India, jump down to

Australia and then pass out in many rumor lines all over SE Asia and Oceania, arriving

back in Siberia for the first time a few hundred kilometers from where it

started.

While these linkings are between

caring enablers and natural nurturers Neville spoke of there been many links

‘falling out’. Misunderstandings can cause people to sever links. Neville would

from time to time tell me not to contact certain ones till he lets me know

things have been ‘cleared up’. I also was rejected by some and after about

seven years re-established good relations. It is not all peace and love. As intimated

before, Neville and I both experienced enabling work at times as emotionally

exhausting.

LACEWEB AND FUNCTIONAL MATRICES

Neville indicated ambivalence about

the nature of the Laceweb in saying ‘whatever it is’ in his Inma poem included

at the start of this research. Inma is another name for Laceweb.

There seems

to be a new spirituality going

around - or a philosophy - or is it an ethical

and moral movement, or a feeling?

Anyway, this Inma religion or whatever it

is - what does it believe in?

Neville was recognizing that

attempting to categorizing the Laceweb is problematic. The Laceweb is not an

organization in the familiar sense. Laceweb is a loosely integrated functional

matrix of functional matrices (holons in holarchy). As a functional matrix

structure, the Laceweb has no central ‘organization’ that any one can ‘belong

to’ or ‘re-present’. Recall that the psycho-social structure and processes

where entangled in Fraser House just as the process of spiraling water

structures the whirlpool. Similarly, the Laceweb is not ‘organized’ into an

‘organization’. Its structure is process energy in action - resonant with the

whirlpools structure that only exists as water in process in a vortex. Just as

the whirlpool is entangled in the water process so the Laceweb’s tenuous

structure is sustained as self-organising human energy in action.

Some indigenous and small minority

people can have as much difficulty coming to terms with this aspect of the

Laceweb as mainstream Western people. While spurning the idea that any one

could represent (re-present) them, Indigenous and small minority people

sometimes expect non-local Laceweb enablers to be ‘from’ or be part of some

organization and to re-present it. It typically takes a while to recognize and

understand the organic nature of the Laceweb. Often it is a few of the women

elders who recognize it first and say that Laceweb action is like their old

ways. Recall that when I outlined grassroots Laceweb networking to a

Bougainvillian with senior management experience in Australian mining

companies, he was able to report upon his return to Bougainville that the

‘nurturer women networks are alive and well in the hills around Arawa. in

Bougainville’. They were already there, though he had never noticed them

before.

On one occasion I had

dialogue extending over four days at a ConFest with a Bougainvillian person

with a Masters degree in Clinical Psychology from an American University. He

was one of three Bougainvillians who had traveled down to see me and experience

ConFest. One was a member of the PNG National Parliament representing

Bougainville. The other was Alex Dawia. Alex, the Clinical Psychologist and

myself shared conversations about Laceweb and socio-medicine. The three of us

co-enabled many hours of workshops. One workshop explored resonances between

Laceweb mediation therapy and the Bougainville tradition of having whole

village to whole village mediation sessions. Around 80 people attended this

workshop. Alex divided workshop attendees into two groups of ‘villagers from

two metaphorical villages in conflict and used real-play to enact a traditional

Bougainvillian whole-village to whole-village mediation session. It was potent.

At the end of the three days of discussions and workshops I

asked the Clinical Psychologist how he saw Laceweb Way resonating in the

Bougainville context. He started by saying that it may be introduced as a

service delivered by centralized bureaucracies. During all the discussions

about ‘self help’ over the three days I had not been aware that he had been

constantly converting what I was saying into ‘service delivery’. I said in

response that ‘service delivery’ was not the way Laceweb worked (Yeomans, Widders et al. 1993). I told him that my understanding was that Laceweb way is

local natural nurturers mutually helping themselves. It was not service through

service delivery people as intermediaries. His face showed sudden recognition

and he beamed. He said, ‘You REALLY mean that it is really

self-organizing; that things just happen because of local energy,

and the enablers support. That is truly extra-ordinary!’ All through the three

days he had been hearing what I was saying and then attempting to squeeze the

ideas into the conventional paradigm of Western service delivery. He then went

on and on about how this self-organizing way would be very appropriate

in Bougainville. I sense that internal decolonisation is a key aspect of

understanding the Bougainville Crisis.

THE LACEWEB AS A SOCIAL MOVEMENT

Turner and Killian define a social

movement as:

‘A collectivity acting with some

continuity to promote or resist change in the society or group of which it is a

part. As a collectivity a movement is a group with indefinite or shifting

membership and with leadership whose position is determined more by the informal

response of adherents than by formal procedures for legitimating authority (Turner and Killian 1972)

Laceweb is a social movement within

the terms of that definition. Laceweb has its origins in Australia over forty

years ago and is spreading throughout the SE Asia Oceania Australasia Region.

Another factor in the forming of the Laceweb is that it has been spreading

among healers and natural nurturers within the most marginalized of people in

the SE Asia, Oceania, Australasia region - the disadvantaged Indigenous and

micro-minority people. Natural nurturers are already present in these

grassroots local communities. That they are already there naturally is

resonant with the Yeomans using local natural resources on their farms. After I

outlined the Laceweb Way during discussions with a person from East Timor in

July 2000, and a person from Aceh in Indonesia in 2003, they both confirmed

that natural nurturer networks aleady existed in their respective communities

back home. Another resonance with Keyline is that the Laceweb is

self-organizing in fostering emergent properties. The only non-local people

with other backgrounds who have been linked into the movement are healers who

are fully resonant with Laceweb ways. I gather there are only a handful of

these people. Typically, non-resonant people are not in the least bit

interested. This minimizes interference from people who would attempt to

subvert the Laceweb way.

A majority of people linked with the

Laceweb are consumed with survival from one day to the next. The Laceweb, as

‘local action’, is just local healers going about their everyday life using

practical wisdom based on local knowings - nothing special - though Neville

passionately believed that this ‘nothing special’ may have the potential to

change the World. Every now and then they may have an opportunity to pass on a

story or two. Laceweb ‘stuff’ does not take them away from the other parts of

their life; it is their life. The

Laceweb is simultaneously very fragile and very strong. Following Tikopia, a

feature of the Laceweb is ‘passing on a mountain trail’ networking. In this the

Laceweb is very resonant with ‘sitting on the train’ informal networking

mentioned by Ireland discussed below; that is, natural nuturers are embedded

within and between local communities and involve socio-cultural action and

interaction in micro-aspects of community life.

In their local communities, other

locals may not know nurturers as ‘Laceweb’ people. Even the local Laceweb

people may not see themselves as ‘Laceweb’ people. Laceweb is very thin on the

ground. In some small remote communities there may be a few ‘Laceweb’ people

and paradoxically, the Laceweb as ‘social movement’ is typically not their scene. For them, Neville’s

macro foci linking into adapting models from the World Order Model Projects may

seem scary and alien (refer later). An international focus may seem alien. Some

Aboriginal natural nurturers have shrunk from any conversation about linking

with Indigenous healers in SE Asia, especially those who may be on a

government’s assassination list. Terry Widders has written that Indigenous

people in the Region generally live in 'contested geographies'. There are

issues of land rights and conflict over resources, for example mines, dams, forests

and fishing. Global Capitalism pressures and seduces cooperation from national

governments to the detriment and potential destruction of the local

Indigenous/micro-minority people. James Speth, a United Nations Development

Program administrator believes, ‘the world has become more economically

polarised’ and that ‘if present trends continue, economic disparities between

industrial and developing nations will move from inequitable to inhuman (Speth 1996; Widders 1997).’

Photo 1 Tailings from Bougainville’s Panguna

Mine fills the valley

with toxic sludge.

Acording to Widders these

disadvantaged people face issues of communal survivability in the physical,

psychosocial and cultural senses. Diverse cultures face issues of their

survive-ability as cultural localities/cultural groups (both dispersed and

compact) and as territorial groups in relation to cultural localities, regions,

environments, and relationship to place. There is also the loss of 'habitat' for hunter gathers and swidden

gardeners (the short-term use of relocated small gardens). With all the above,

they daily face the economics of survivability as individuals and communities (Widders 1997).

Within the Indigenous/micro-minority

communities in the Region there may be energy resisting the forces creating the

issues outlined above. However, within the Laceweb social movement it is

‘healing’ that is the central focus and potential for social transformation,

not ‘power’ or ‘resistance’. The Laceweb functions at the socio-cultural level.

Laceweb action is for healing, for

friendly relating, - quality living, psychosocial wellbeing (being well),

celebrating and nourishing in all its forms. As well, it is for a culture (as in ‘way of life’) that

meets the needs of the locals. This is very ‘Yin’ in focus.

The Laceweb is not ‘against’ anything - there is no ‘Yang’

element. It does not want to ‘preclude’, or ‘resist’, or ‘attack’. This appears

to be a big difference between the Laceweb and the new Latin American social

movements discussed below. When warrior types within some Indigenous groups

discovered that Neville was a psychiatrist/barrister, they invariably sought to

have him take up their fight with

authorities. Neville always refused.

In a conversation with Neville in May 1999 he said, ‘Healing is the ultimate

subversive act. There is nothing so subversive as healing to ‘warriors’ within

an aggressive type of system, as it threatens their value system’. Laceweb ‘Yin

healing’ is all the more subversive for its subtleness. The quiet and

unobtrusive Yin healing within the Laceweb Yin ‘equality reality’ is typically

not noticed, or if noticed is dismissed as weak, contradictory, and irrational

by the ‘warrior’ system. In Fraser House, half were aggressive under-controlled

over-active warrior types and they mellowed. Even if Yin healers are not in the

least bit interested in politics, their healing may be profoundly subversive

and in the medium to long term (perhaps hundreds of years) may have major

consequences for political change.

The view that appears prevalent within

the Laceweb is that country-based governments, at national, state or local

levels, are not relevant to the movement’s actions. Recall that Neville viewed

them as already dinosaurs in a 500-year timeframe. No evidence has been found

that the Laceweb movement as ‘movement’ has ever accepted government funding.

Yang activists in social movements in

the Region fighting the status quo, are also warriors. Healing equally

threatens their value system. They also dismiss healing as weak and

ineffectual. Yang activists may become interested in the subversive

consequences of healing if they do perceive this, but not the healing per se -

its just not ‘their thing’. They can change – like the former ‘bank robber’

who, with over 20 years of criminology research behind him since leaving Fraser

House, was researching healing ways at Petford when I met him in 1992.

People within the Laceweb typically do

not see themselves as in any way political. They are healers and enablers of

others’ healing. Those within the Laceweb who do take the macro view of the

Laceweb, typically see any wider transformative potential of the Movement as

possibly happening in a few hundred years time. Some fully recognize the

considerable potential of the Laceweb as a long-term political change agent,

and that this potential lies in the possibility of producing change rooted in

healing everyday behavior and action. Some are holistically strategic from the

micro to the macro. They persist.

Throughout parts of the Region Laceweb

linking operates on a ‘need-to-know’ basis. Many of the people involved want to

keep a very low profile. Put bluntly, some healers are wanted dead by

Governments in the areas they live in. As stated, healing may be the ultimate

subversive act. Someone else revealing a Laceweb person’s details to another

person without that person’s permission would mean that the link with the

betrayer would be severed permanently. This limited knowing of who is involved

is not a weakness. It is a strength. It is isomorphic with neural networks

where only four adjacent connections are typically activated as things fly

along the neural pathways. No one can find out the ‘member list’ in order to

undermine the movement. The list does not exist. No one knows more than a few

of the others involved.

Many Laceweb people are riddled with

dysfunction and traumatized. Fraser House, Fraser House Outreach and Laceweb

have demonstrated that the traumatized do have immense potential, and can act

well in self and mutual help. Other Laceweb people from extremely remote places

may be ‘really together’ people. Their integrity, articulateness, profound

caring and wisdom may be far and away from any notions of ‘rudimentary’. For example, a number of a

small group of women from a remote Aboriginal community attending the Small

Island Coastal and Estuarine People Gathering in 1994 had university degrees

and one had completed her Masters in community development. They had ‘Talent’

with a capital ‘T’ in First World terms. They engaged in loving wisdom in

action grounded in a 30,000 plus tradition of co-existing well with all life on

Earth.

Laceweb nurturing is freely given;

healing and wellbeing ways are past on freely. Healing and wellbeing ways are

not turned into commodities to be appropriated, bought, packaged and sold. Ways

do not arrive as ‘owned by somebody’ or labeled as nouns. They arrive as

micro-experiences to be freely shared, experienced, embodied and passed on to

others freely. ‘Healing ways’ may arrive as accounts of micro-experiences -

little bits of behavior. Rumors may be carried within stories, and stories may

be carried within rumors. Typically, the original ‘source’ of a rumor does not

arrive with the rumor and is undiscoverable, and that this is the case, is of

little account. The rumor may, and typically does, cross ethnic and cultural

boundaries. It may arrive with little of other people’s ‘culture’ attached. Any

remnants of ‘culture’ that are attached may, and typically are, removed in the

local adapting and testing. Rumors may be modified and changed both in their

testing and in their passing on. Rumors may have a malleable life of their own

and may return to their source unrecognizable and exquisitely relevant and

enriched for the same, and or differing needs. Rumors may travel with values

attached or embedded. Values may be enriched along the way. Some action values

may be loving, caring, nurturing, being humane, being well, playing, dancing,

singing, music making, drumming, celebrating, peacehealing, as well as

respecting and celebrating diversity (Yeomans 1992; Yeomans 1992). The rumors values networking may be

both morphous (having form) and amorphous (without form) in some respects,

contexts, times and places. Recall that Neville believed that changing values

is a potent way to change culture. For example, in 1994 the rumors values

network took tangible and palpable form as cultural locality at the Small

Island Coastal and Estuarine People Gathering Celebration in Far North

Queensland. During this Gathering, morphous networking through both amorphous

and morphous healing storytelling abounded.

The German word ‘schien’ is apropos -

as in ‘appearance’ (Pelz 1974, p. 88-89, 115). Some sparkle may attract ‘like

people’ who like what they see, hear and feel. Appearance may reveal, as Jesus

did with parables and metaphors. Those unlike will not like, and for them,

appearances may deceive rather than reveal, so that the rumor, ideas and action

may be not noticed, or dismissed as irrelevant or moronic. As the Bible writer

Mark wrote (Chapter 4, Verse 9-10):

‘And

Jesus concluded, ‘Listen then if you have ears!’ When Jesus was alone, some of

those who had heard him came to him and asked him to explain the parables.’ Jesus said to these that they had been given

the secrets. Others on the outside would hear the parables and look at them and

not see, and listen and not hear.

Jesus spoke of becoming ‘fishers of

men’. In today’s terms he was talking about networking with resonant people -

on worker’s trains, or on Tikopia’s mountain pathways, or in Fraser House or in

dispersed urban and remote area networking.

The Laceweb movement has created

public spaces for itself by spreading in rural and remote regions where space

for healing possibilities may be readily available. Typically, the Laceweb way

is to go out of one’s way not to

attract attention to one’s self. That the Laceweb is difficult to perceive is a

blessing. Those who are resonant with the Laceweb tend to be able to readily

perceive it. Warriors may be looking directly at the Laceweb and not see it.

The Laceweb appears to have a

considerable number of participants. However, there is only a small number at

any one location and people typically only know a few links between these small

groups. Neville said that rumor has it that the Laceweb linking has reached

natural nurturers within over half of the Indigenous groups in the SE Asia

Oceania Australasia Region and that around half of the World’s Indigenous

peoples are in the Region, that is, the Laceweb has spread to having links

within a quarter of the Worlds Indigenous peoples.

The Laceweb is informal throughout; it

is neither top-down nor bottom up - rather, it’s a flat local and laterally

linked functional matrixing or networking. Large segments may have no sense of

being in any way in a ‘social movement’ or ‘structure’. To reiterate prior

comments on denominalizing, Laceweb is more ‘energy in action’ than ‘thing’;

like the slogan says, ‘The best things in life are not things.’ It is

‘networking’ rather than ‘network’.

The Laceweb has both individual and

consensual collective decision making among local people at the local level,

and/or actions emerge out of individual and shared energy – where what to do

emerges as shared understanding and mutual commitment to action rather than

formal or even informal decision processes. A person who can read the group

mood may say for example, ‘So we all gather at sunrise and erect a footbridge

at the narrows tomorrow.’ If when he or she gets there no one else turns up,

the mood was misread. If the bridge is already under way that person did read

the mood. The person who reads the mood of the community regularly emerges as a

special person.

The Laceweb has no leaders, or rather,

everyone involved is a leader. Typically, there is no social distance between

active people at the local level. People from one locality tend to only know up

to four sequential links in the non-local networking with increasing social

distance between the more remote links. Beyond that, social distance is total -

they just don’t know others in the Laceweb networking at all. No one is a ‘member’ and there is no

leadership of the Movement processing. While local people may take the lead in

healing action, they are not leaders ‘over’ anyone.

The Laceweb focuses on taking action

to heal local needs and consensually validating what works. What works may

informally become local ‘policy’, defined as, ‘that which works’. What works

may be passed on as ‘rumor’ for others to check. There is little focus on grand

theory or macro ‘aims’. The Laceweb follows the continuous prolonged action

research model and naturalistic enquiry. Any theory that does emerge comes from

action that works. Action is prompted/guided by local wisdom about ‘what is

missing in our well-being’ and received rumors about what has worked for

others. The Laceweb way is ‘action’ not ‘talk about action’. It is ‘experience’

rather than ‘talking about experience’. Stories tell of action that worked or

possibilities for action, not ideas and theories. Receiving rumors as stories

may be profoundly healing (Gordon 1978).

The Laceweb is spreading intentionally

in rural and remote places - away from mainstream negating energies. From deep

within it’s own Zen-like logic, the Laceweb’s weakness is it’s strength.

‘Inefficiency’ is a mainstream ‘quantitative’ concept that has little

relevance. ‘Inefficiency’ may be very efficient from a different

viewpoint. For example, Fraser House jobs being done by those who could not

do them was extremely inefficient in terms of job completion. However,

experience is the best teacher and the process was very efficient at

transforming patients and that was the central focus. Seeming contradictions

typically come from perceiving from the single logical level. The Laceweb is

both simple and complex and operates at a number of logical levels (Bateson 1973). From Laceweb’s multiple

perspectives, seeming contradictions and paradoxes may disappear.

COMPARING LACEWEB AND NEW LATIN

AMERICAN SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

Rowan Ireland has written a paper

titled, ‘Sitting on Trains’. It is placed in the shantytowns on the outskirts

of São Paulo in Brazil (Ireland 1998). These were ‘home’ to a social

movement that Ireland had been researching in the late eighties. Central to that social movement’s aims were

improving their local habitat. Ireland writes of his returning to investigate

the social movement ten years later. The first part of his article paints a

very gloomy picture. ‘I had lost sight of my social movement. I would find

myself recording only happenings of chaos, breakdown and anomic

disintegration’. He describes conditions as ‘pathetic’. The destitute were so

concerned with sheer survival that there was no energy for any ‘social

movement’. In contrast to ongoing academic writing of how social movements

operate, Ireland describes his ‘movement’ as, ‘a nightmare story.’

During this revisit to his old

research place Ireland had been regularly traveling backwards and forwards by

train along the 55 kilometers between the out-lying shantytowns and São Paulo.

While so traveling he had been engrossed in his academic reflections as to what

could have killed the social movement he had been studying. Then there is this

delightful moment on the train where Ireland suddenly looks up and sees his

social movement. He is surrounded by it. Instead of it being dead as he

thought, it is very much alive and well in this public space of the peasants’

train. Like Big Group at Fraser House that train was cultural locality

concentrate. This is resonant with Neville’s use of ‘public place and space’ in

Fraser House. Ireland had been blind to what was surrounding him. Now before

him he suddenly sees a profusion of zest and community, avid conversations,

discussion circles and debates, orators talking on all manner of subjects, the

repartee of shoulder-to-shoulder hecklers and the belly laughs of the crowd as

audience. There were also poets, musicians, jugglers and other buskers -

beggars’ banquets and a thriving paupers’ market extending even to

coals-roasted peanuts from the kerosene tin – Neville’s cultural healing

action. What Ireland describes has resonance with SE Asia Oceania Australasia

Indigenous people’s use of sociomedicine in everyday contexts. Here on the

train, alive and well, Ireland finds what he calls ongoing ‘invention’ and

‘structuration’ - change potential bubbling within everyday socio-cultural

life. For Ireland it was his social movement, but in a different form. Perhaps

this form had existed all along and he like other theorists just hadn’t seen

it. Among the human energy on the train all manner of happenings and ideas were

being passed on as stories and rumors - fragments of subjective experience were

being melded for the possibilities of enriching life.

What had prevented Ireland seeing all

of this immediately? New forms of social

movements were emerging in Latin America and they were not where theorists were

looking. These movements were not taking the familiar form, and hence they had

gone un-noticed by social theorists. In introducing these ‘behavior on trains’

insights, Ireland refers to Evers’ writings on new social movements in Latin

America (Evers 1985). Evers suggests that the ‘innovative

capacity of these new social movements appears less in their political

potential than in their ability to create and experiment with different forms

of social relations in everyday life’. Ireland writes that ‘the astonishing

sociability of Brazilians appears to flourish just when it is assumed dead on

the mean streets’. From Evers - ‘By creating spaces for the experience of more collective social relations, of a

less market-oriented consciousness, of less alienated expressions of culture

and of different basic values and assumptions, these movements represent a constant

injection of an alien element within the social body of peripheral capitalism

(my italics) (Evers, 1985). This resonates with Neville’s 1971 paper on Mental

Health and Social Change where he spoke that in times of social transition, ‘an

epidemic of experimental organizations develop. Many die away but those most

functionally attuned to future trends survive and grow’ (Yeomans 1971a; Yeomans 1971b). Like the new Latin American

movements, the Laceweb’s transformatory potential is at the psycho-socio-cultural

level. To paraphrase and adapt Ireland, the Laceweb focuses on healing socio-cultural

and socio-psychic patterns of everyday social relations penetrating the

microstructure of local communities.

A similarity with the Latin American

New Social Movements is that for many, the Laceweb appears ‘weak, implausible,

fragmented, disorganized, discontinuous, crippled, and contradictory.’ That it

may appear this way to mainstream people is a strength. The movement may be

ignored as inconsequential by those who may otherwise seek to harm. Laceweb

people tend to immediately sense people who want to come in and ‘rectify’ the

supposed weaknesses. There is little scope for intrusion by elements who may

seek to transform the Laceweb towards mainstream ways. Typically, any attempt

to do this is rejected by Laceweb people. If outsiders do manage to transform

bits of the Laceweb, it typically relates to only a very small part of the

network, and the other parts of the Laceweb sever working ties with this

transformed part. Put simply, that part ceases to be Laceweb.

Like Ireland, Evers also seeks to

identify aspects of new social movements in Latin America. He suggests firstly, that “political power’

as a central category of social science is too limiting a conception for the

understanding of new social movements.’ Rather, ‘their potential is mainly not

one of power, but of renewing socio-cultural and socio-psychic patterns of

everyday social relations penetrating the micro-structure of society’. To

express it in different words, ‘the transformatory potential within new social

movements is not political, but socio-cultural’. All this again resonates with

Neville’s frameworks as well as Fraser House and its outreach. It is also

resonant with ancient indigenous sociomedicine for social cohesion.

Evers identifies this shift from

preoccupation with ‘power’ in the Latin American context. ‘It is my impression

that the ‘new’ element within new social movements consists precisely in

creating bits of social practice in which power is not central; and that we

will not come to understand this potential as long as we look upon it from the

viewpoint of power apriori.’ New

social movements are evolving relations other than ‘power relations’ and

‘market relations’. The dominant culture has the base of it’s power embedded in

modes of perception and orientations, as well as beliefs and values that are

generally operating below awareness on the socio-cultural and socio-physical

level of everyday life (Kuhn 1962; Kuhn 1996).

The new social movements are a significant danger to dominant systems,

says Evers, precisely because of their potential to undermine this very base.

The new social movements tend to put into question the ‘unconscious automatism

of obedience’ within mainstream at the socio-cultural and psycho-socio-physical

levels.

While this ‘danger’ to mainstream

could be in the long term, it is this potential to produce change, ‘rooted in

the everyday practice and in the corresponding basic orientations at the very

foundations of dominant society’, which may prove to be the source of the most

profound change potential of these new movements. They may turn out to be more

political in their consequences than movements in direct political

confrontation with the dominant system.

Evers commented that, ‘the question of

re-appropriating of society from the State has become thinkable. Neville

created a structure and processes so that re-appropriating society from the

State was actionable. In Fraser House Neville was reappropriating Society from

the State in a State hospital. To quote Evers again, all in Fraser House,

rather than having the State internalized, they are ‘generating and

experiencing states (experiences) of their own making’. A central theme in all

of Neville’s work was re-appropriating society from the State. Rather than

having the State ‘run’ their lives, local Laceweb people are start taking back

their own lives. Instead of having the never questioned State internalized,

they are generating and experiencing states (experiences) of their own making.

Evers’ comment that the ‘new’ within

these movements is also archaic very much applies to the Laceweb. It is reported that very old Indigenous

people often say that some Laceweb happening is ‘the old way’ (conversation with

Yeomans, N., Nov 1992)

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF PLACE

During the years 1993

through to 1998 when I started this Thesis my understanding was that the main

reason Neville was evolving networks in Far North Queensland and the Darwin Top

End in Australia was to keep away from dominant interests that may seek to

undermine and subvert the social action he and others were engaged in. I found

Neville’s paper, ‘Mental Health and Social Change’ (Yeomans 1971a; Yeomans

1971b) in his archives in

October 1998. It is a scribbled half page note and hand sketched diagram

written back in 1971. It discusses the nature of epochal transitions. It

revealed that Neville had specifically chosen Far North Queensland because of

its strategic locality on the Globe as a place to start transitions towards a

Global transition. Still I did not take this seriously and immediately turned

the page to the next item. I sensed that it was more to do with being ‘away

from mainstream’. I did not realize at the time that this was a crucial

document specifying Neville’s core framework. In this, ‘Mental Health and

Social Change’ file note Neville clearly specifies epochal transitions. It is

an example of how my pre-judging mind limited my seeing. Neville wrote:

‘The take off point for the next cultural

synthesis, (ed. point D in Diagram 1 below) typically occurs in a marginal culture.

Such a culture suffers dedifferentiation of its loyalty and value system to the

previous civilization. It develops a relatively anarchical value orientation

system. Its social institutions dedifferentiate and power slips away from them.

This power moves into lower level, newer, smaller and more radical systems

within the society. Uncertainty increases and with it rumor. Also an epidemic

of experimental organizations develop. Many die away but those most

functionally attuned to future trends survive and grow.’

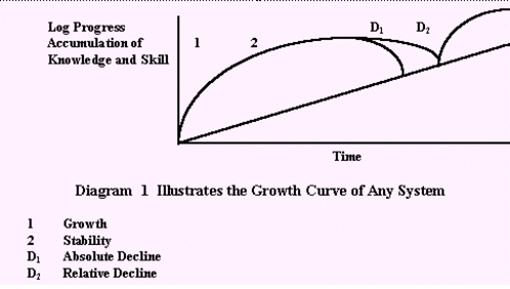

Diagram 1 The Growth Curve of any System

In saying, ‘Its social

institutions dedifferentiate…’ Neville is talking about a shift away from

dynamic differentiated adaptive far-from-equilibrium states to non-adaptive

sameness. With the words, ‘those most functionally attuned to future trends

survive and grow’ Neville was hinting at his aspirations. In the same 1971

document Neville went on to talk about the strategic significance of Far North

Queensland as a marginal place to explore Global transitions:

‘Australia exemplifies

many of these widespread change phenomena. It is in a geographically and

historically unique marginal position. Geographically Asian, it is historically

Western. Its history is also of a peripheral lesser status. Initially a convict

settlement, it still remains at a great distance from the core of Western

Civilization. Culturally it is often considered equivalent to being the

peasants of the West. It is considered to have no real culture, a marked

inferiority complex, and little clear identity. It can thus be considered

equally unimportant to both East and West and having little to contribute.

BUT - it is also the only

continent not at war with itself. It is one of the most affluent nations on earth.

Situated at the junction of the great civilizations of East and West it can

borrow the best of both. Of all nations it has the least to lose and most to

gain by creating a new synthesis (Yeomans 1971a; Yeomans

1971b).’

Neville wanted the Far North as a

linking place for evolving networks throughout the SE Asia Oceania Australasia

Region.

A MODEL FOR A 200 YEAR TRANSITION TO A

HUMANE CARING EPOCH

Back in 1993 Neville told me to remind

him to get me a paper that he had written back in 1974 called, ‘On Global

Reform – International Normative Model Areas’. Neville later told me he could

not locate the document. It was not until two months after Neville’s death that

I found this paper (Yeomans 1974). This is one of, if not the most

significant papers Neville wrote. Once I read it I suddenly knew of the

strategic significance of the, ‘Mental Health and Social Change’ paper

mentioned above that I had spotted in the archives in October 1998. As stated,

at the time I first read this other paper in 1998 it held no special import in

terms of specifying the place to commence Global epochal change. I saw it only

as identifying a place to minimize interference from mainstream.

In that ‘On Global Reform’ paper

Neville wrote about his involvement in the New State Movement and its potential

relevance for his ideas. At one level this paper was written for the Australian

Humanitarian Law Committee and as a paper submitted on humanitarian law for his

law degree (Yeomans 1974). At a far higher level, I suspect

that this paper is the Key Laceweb document. It specifies Neville’s

Epochal Quest and his big picture long-term framework for achieving epochal

change. In this paper, in talking about one model of Global Governance being

put forth by people described as ‘normative realists’ (and Neville recognized

downsides of their position), he wrote:

‘The global transition

model of the normative realists has emphasized a credible transition strategy

in the move towards a more peaceful and just world. However it is necessary to

make such a strategy both meaningful and feasible to persons and groups, and to

underpin that world level analysis with relevant application to individual

communities. An attempt will be made to do this in an Australian context by presuming

the creation of an Inma in North Queensland.

Recall that Neville

structured Fraser House to be a ‘transitional community’. For Neville, that

earlier exploring of the nature and behaviors of transitional communities was

towards the later evolving of ‘Global transitional models’. Notice Neville’s

linking of macro and micro in the above quote – using the principal, ‘Think

Globally. Act Locally’:

1.

A World level analysis

2.

A global transition model

3.

A credible transition strategy

4.

A strategy both meaningful and feasible to persons and groups,

5.

Underpin that World level analysis with relevant application to

individual communities

Notice that Neville uses

the expression, ‘presuming the creation of an Inma in North Queensland’.

Neville would regularly presume that something already existed and start

inviting people to be a part of it. This is resonant with what Milton Erickson

would do in therapy – he would have them acquire new competences and then put

people in their imagination in a future world where they experience using these

competences well, and let them experience that world. Bandler and Grinder

called this, ‘future pacing’ (Bandler 1975; Grinder, De

Lozier et al. 1977; Bandler, Grinder et al. 1979; Dilts, Grinder et al. 1980;

Bandler, Grinder et al. 1982; Bandler 1984; Bandler and Gordon 1985). Neville would so presume Inma that it did ‘exist’, people never

knew the extent of it. One person in Byron Bay that I talked to when gathering

people of artistry to attend the Small Island Gathering, called this Laceweb

‘future pacing’, ‘using smoke and mirrors’. It is the schein – ‘the appearance

that reveals and deceives’ (Pelz 1974). Neville actualized Inma from a potent articulated virtual

reality repeated passionately. Neville continued:

‘It is submitted that

….consciousness-raising,….would occur firstly among the most disadvantaged of

the area, including the Aborigines. Thus human relations groups on a

live-in basis could assist both the growth of solidarity and personal freedom

of expression amongst such persons.

In initial experiences along this line

the release of fear and resentment against whites has led to a level of

understanding and mutual trust both within the aboriginal members and between

them and white members (Yeomans 1974).’

In the last paragraph, the ‘initial

experiences’ Neville was referring to was the Human Relations Workshops in

Armidale and Grafton in 1971-73 (University

of New England, Dept. of University Extension et al. 1971). In saying,

‘the growth of solidarity and personal freedom of

expression amongst such persons’ Neville was referring to the experience of

participants in those workshops. Neville spoke of people regaining their voice

and forging inter-community cooperating networking.

Neville further links the

Inma framework to a tightly specified place with the following:

‘Turning to the ethics and ideology of Inma people; it is

axiomatic that for a life-style and value mutation to occur in an area such

territory needs to be in a unique combined global, continental, federated state

and local marginality. Globally it needs to be be junctional between East and

West (Parkinson

1963) at least

geographically and in historical potentiality. At the same time at all levels

it needs to be sufficiently distant from the centers of culture and power to be

unnoticed, unimportant and autonomous.’

The words ‘unnoticed, unimportant and

autonomous’ are apt descriptors of the Laceweb networking. Recall that in 1963 when Neville traveled the World

speaking to Indigenous peoples about the best place in the World to begin

evolving a normative model area, the constant feedback was that Far North

Australia was the most appropriate. Neville told me many times that Far North

Queensland and the Darwin Top End was the most strategic place in the World to

locate Inma. To reiterate, initially I kept thinking he meant the best place

for least interference. While ‘least interference’ was important, he was really

meaning the best place to start a Global Transition. Neville told me that

action would be best above a line between Rockhampton on the East Coast of

Australia, and Broome on the West Coast. In 1997 Terry Widders pointed out that

the Asia Oceania Australasia region contains around 75% of the global

Indigenous population (approximately 180 of 250 million). In the same vane, it

contains 75% of the World's Indigenous peoples (Widders 1997). The Australia Top End was a marginal

locality adjacent the marginal edge of SE Asia Oceania.

Further in the ‘On Global Reform’ monograph Neville wrote

the following about 'utopography':

‘At the same time 'utopography' provides models, which normative

realists can experiment with as transitional strategies. These can be

implemented in naturally occurring model areas providing Inmas for evaluation

and support by global theorists and researchers. (Yeomans

1974).’

Notice the expression, ‘naturally occurring model areas’

– resonant with Keyline. These places already existed ‘naturally’ and he could

support nature.

Laceweb action is always locals taking action to meet

local needs. Within the Laceweb, ‘Utopia’ is not an abstract ideal or an

impossible dream. Action is continually evolving an every-widening pool of

‘ways that work’. These are passed on and consensually validated by action of

other locals. Local utopias are being experientially and inter-subjectively

constructed as everyday lived experience. Action carries possibilities in

peacehealing towards evolving varied utopias that respect and celebrate their

individual and respective diversities. This allows possibilities for a Global

epoch based on humane caring for all in the natural and social life world. The

Laceweb is in no way promoting a common social utopia (More 1901).

Neville had been reading the writings of Richard Falk of

Princeton University in USA and other normative realists who were connected to

the World Order Model Project, called ‘WOMP’ for short. Falk quotes Robert Heilbroner's incisive chastisement of utopian thought

in commenting upon someone’s utopian writing:

'Like

all utopias, it is a joy to contemplate. Alas, like all utopias it contains not

a word as to how we are to go from where we are to where we are supposed to be (Falk

1975, p. 347).’

In

stark contrast, Neville

wrote about Inma being a place to explore various utopias, and where

local aspiring utopias can respect and celebrate other aspiring utopias. Neville evolved practical action towards multiple utopias

where every aspect may be tested by the locals in respective local contexts.

What worked may be repeated by locals in local contexts.

Neville’s monograph then proceeds to

outline his 200-year transition process. Neville writes of adapting one of the

World Order Models Project’s (WOMP) models toward what he described as a ‘more

problem-solving and value priority functionalism’. Neville drew upon Richard

Falk’s book, ‘A Study of Future World’s (Falk 1975) and

Falk’s Journal article, ‘Law and National Security: The Case for

Normative Realism (Falk 1974)’. Neville adapts Falk’s model using

Falk’s T1, (‘T’ for ‘transition’) V1 (‘V’ for ‘Values’) frameworks though

Neville gives new meanings to the Vn values and specifies the Tn transition

phases slightly differently. Neville describes what he saw as a possible 200

year transition process in the following terms (Yeomans 1974). The follow segment places Neville’s

early paragraphs in context:

‘This design involves the conceiving

of a three-stage transition process (T1-T3) (ed. Where T1 T2 and T3 signify

three transition processes):

Tl = Consciousness-raising in national

Arenas

T2 = Mobilization in Transnational

Arenas

T3 = Transformation in Global Arenas’

‘The new system is based on the

performance criteria (V1 - V4) of peacefulness, economic equity, social and

political dignity and ecological balance (ed. Where V1, V2, V3, and V4 are

values).

Falk’s transition phases were:

T1 = Consciousness raising in Domestic

Arena

T2 = Mobilization in Transnational and

Regional Arenas

T3 = Transformation in Global Arena,

and

T4 = Consciousness Phase 2 Personal

Social Arenas

Falk’s values were:

V1 = War Prevention

V2 = Economic and Social Wellbeing

V3 = Human dignity, and

V4 = Ecological Quality

Note that Neville has Consciousness

raising in Personal Social Arenas happening first – not last. Neville’s model

starts with grassroots consciousness raising.

As hinted at in the prior section

comparing Laceweb with Latin American movements, with Laceweb, social action

focuses on transforming evolving at the psychosocial and psycho-emotional

levels. Neville was setting up processes for ‘economic equity’ and political

dignity’ not through economic or political power-focused pressure, rather,

through gentle transforming at the psychosocial and psycho-emotional levels.

The economic and the political transforming would be preceded by peacefulness

and ecological balancing and transforming action in the widest sense. Neville

went on to describe proposed political frameworks:

‘The political organs have tripartite

representation:

1.

peoples,

2.

Non-government

Organizations, and

3.

governments.’

Notice the bottom up ordering.

‘Surely one would here add a fourth

representation of individuals by global voting. The global transition model of

the normative realists has emphasized a credible transition strategy in the

move towards a more peaceful and just world. However it is necessary to make

such a strategy both meaningful and feasible to persons and groups, and to

underpin that world level analysis with relevant application to individual

communities.’

‘An attempt will be made to do this in

an Australian context by presuming the creation of an Inma in North

Queensland.’

‘It is submitted that T1 consciousness-raising, [Tl (C -

R)] would occur firstly among the most disadvantaged of the area, including the

Aborigines. The next step could be focusing their activities on the Inma. This

would be accompanied by widespread T1 activities in the Inma, conducted largely

by those trained by previous groups. Aborigines from all over Australia and

overseas visitors would be involved as has begun. Over a number of years the

Indigenous population of the Inma would be increasingly involved, both black

and white. Co-existing with later T1 activity is a relatively brief

consciousness raising program with the more reformist humanitarian members of

the national community, i.e. largely based on self-selected members of the

helping and caring professions plus equivalent other volunteers. However their

consciousness raising is mainly aimed at realizing the supportive and

protective role they can play nationally, in guaranteeing the survival of the

Inma beyond their own lifetimes, rather than trying to persuade them actually

to join it by migration.’

In the years following 1974 when he

wrote this paper Neville followed through with the above social action. Neville

implemented his networking firstly in the Queensland Top End and in the early

Nineties extended this to the Darwin Top End. I can see that in 1986 when I

first met him I slotted into the sentence:

‘Co-existing with later T1 activity is a

relatively brief consciousness raising program with the more reformist

humanitarian members of the national community, i.e. largely based on

self-selected members of the helping and caring professions’.

I was one of those. In writing,

‘rather than trying to persuade them actually to join it by migration’, Neville

actively encouraged me not to shift North. He said I was most valuable as a

distant resource person. In supporting the Laceweb Homepage and doing this

research perhaps I may contribute to, ‘guaranteeing the survival of the Inma

beyond their own lifetimes.’

Recall the Inma poem at the

commencement of this Thesis. In speaking of the INMA:

‘It

believes in an ingathering and a nexus,

of human persons values, feelings, ideas and actions.

Inma

believes in the creativity of this

gathering together and this connexion of per-

sons and values,

It

believes that these values are spiritual,

moral and ethical, as well as humane, beauti-

ful, loving and happy.’

Note the merging and interweaving – first the

ingathering, then the nexus, and it’s a nexus of human

persons values, feelings, ideas and actions. He refers to the creative

potential and the self-organizing connexity, and that the natural nurturers are

homo amans – the loving, spiritual, moral, ethical, humane, beautiful, happy

lovers of the region. The poem is saturate with Cultural Keyline Way.

Neville continues with the T2 level:

‘T2 has two subunits:

T2 (a) commences with the mobilization

of extra-Inma supporters nationally.

T2 (b) moves to the mobilization of transnationals who

have completed T1 consciousness raising in their own continents. That mobilization

is of two fundamentally distinct types:

T2 (b)(i) mobilization of those who

will come to live in, visit, or work in, the Inma.

T2 (b)(ii) mobilization of those who will guarantee

cogent normative, moral and economic support combined with national and

international political protection for its survival.’

‘By T3, the effects of T1 and T2 have

largely transformed the Inma, which is now a matured multipurpose world order

model. Its guidance and governance will be non-territorial in the sense that it

extends from areal to global. Politically it is territorial, economically it is

largely continental; in the humanitarian or integral sense it is continental

for Aborigines and partly so in other fields, but it is largely global.’

‘T3 for the Inma is then nearing completion, while its

ex-members who have returned to their own continents are moving these regions

towards the closure of T1, the peak of T2 and the beginning of a global T3.

This is perhaps 50-100 years away. By the time of the peak of global T3

humanitarian consensus provides the integral base for development of a World

nation-state of balanced integrality and polity. World phase completion could

perhaps be 200 years away (Yeomans

1974).’

As far as I can determine T1

consciousness raising is evolving in the Far North Queensland Inma, with links

across Northern Australia and the Darwin Top End. T1 consciousness raising is

occurring among marginalized people across the SE Asia Australasia Oceania