Respectfully

Resocializing

Going Down the

Rabbit Hole

Emerging from

Post Doctoral

Clinical

Sociology Research

Currently a live

document with multiple updates every day.

Tues

day 28th March

2017

Email: tcenablers@gmail.com

About ways that work in transforming people

and society:

o Respectfully re-socialising

o Stopping conflict in all of its forms[1]

o Evolving enabling[2]

atmospheres and environments

o Evolving Vibrant Communities

o Increasing effectiveness in Therapeutic Communities

o Setting up community processes for:

o Stopping family violence

o Stopping bullying

o Stopping addictive behaviours

o Stopping racism

o Re-constituting[3]

society following man-made and natural disasters

o Enlivening schools in areas of situated poverty

o Revitalizing Grandparenting, Parenting and Childhood

o Re-locating, settling, and habilitating displaced people

o Re-socialising the Radicalized

o Evolving thriving multicultural communities

o Evolving humane caring alternatives to Criminal and

Psychiatric Incarceration

o Reviving closed Therapeutic Communities

o Having vibrant Community doing things and being the change process (rather than

government, organizational, or business services)

o Evolving our Unique Potentials in making better Realities

perhaps

it’s a source of precious gems

not

a manual

and

whether gems

depends

on you

as

the potency of these gems

is

a function of you

not

the gems

and

a function of how

you

weave

the

gems

and

imaging a special place

filled

with these gems

healing

transforming power

only

tapped by folk

relating

with them in special ways

and

using these same ways

in

relating with each other

within

contexts

framed

in special ways

something

to do with subtle loving energy

surrendering

for

evolving

potent

realities

Contents

Assuming a

Social Basis of Mental Illness.

Margaret Mead the Anthropologist

Visiting Fraser House

Constituting

Fraser House as an Institution.

The

Potency of Social Relating

The Resocializing Program

– Using Governance Therapy

The

Potential Potency of Small Moments

Identifying with Transforming

Action

Legitimising Fraser House by

Establishing the Psychiatric Research Study Group

Legitimation Supporting

Fraser House and All Involved

Legitimating Under Threat of

Reality Breakdown

Research

Questionnaires And Inventories - Neville Yeomans Collected Papers

A List Of Advisory Bodies And Positions Held By Dr

Neville Yeomans

DIAGRAMS

Diagram 1 Map of Section of Gladesville

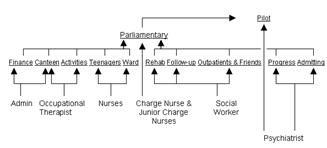

Diagram 2 Resident Committees and the Staff Devolving their Traditional Roles to

Become Healers

Diagram 3 Recast of Diagram Two

PHOTOS

Photo 1 One of the

Fraser House Dorms

Together we make things happen

and together we’re transformed in the process

GOING DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE

Pervasively, throughout the

world social systems of systems have evolved with a massive array of control

processes for the control of everyone with no one in control.[4] The expression ‘going

down the rabbit hole’ hints at entry

into the unknown. The red pill and its opposite, the blue pill, are popular culture

symbols representing the choice between embracing the sometimes painful truth

of reality (red pill) and the blissful ignorance of illusion (blue pill).

You take the blue pill, the story ends. You wake up in your bed and believe

whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill, you stay in Wonderland, and

I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.

In the Matrix[5] film the term red pill referred to a human that is aware of the true

nature of the Matrix. In Fraser House they were re-defining

the nature of the red pill – here you’ll experience living well in the Matrix

and support re-humanizing the Matrix. The Matrix is the Social System of

systems of control with no one in control.

A major means of control is

socializing. Within that a major means of control is the slowing down of

imagination so that a fundamental mural[6] about reality can be set

in concrete and therefore never noticed and rarely or never questioned. It’s

about time - this E-Book looks back (to the 1960s) to look forward to present

action towards respectfully re-socializing in the process of evolving new realities where people can thrive in evolving new thriving Again -

it’s about time.[7]

In the early 1960s

there was an example of Resocializing that Worked. In this E-Book

‘Resocializing’ refers to actions that profoundly respect the individual and

the collective.[8]

This 1960s example may be a model for our Age. This social action example was

an experimental facility called Fraser House, an

uncharacteristic psychiatry Unit exploring non-drug community processes.

This

Unit took in seriously at-risk Residents transferred from the wards at the back

of mental hospitals where these hospitals would put patients that they could not help.

Fraser

House also took in people from jails whom the authorities would not give a day

of parole. Processes that worked were replicated or adapted in later contexts

within the Unit. After operating for some months this Unit was returning these

Residents to living well in Society within twelve weeks. In the early drafts

of this E-Book it commenced as a dense account unravelling how the tightly woven

Fraser House Way worked in re-socialising

these people. This E-Book has emerged as something very different. It is now

more a dense account of how the Residents

socialized Fraser House and found

themselves in the process. Before coming to Fraser House, the Residents

tended to experience life as without meaning (meaningless), and without norms

(normlessness). They were typically isolates that did not belong. They were

misfits.

Yeomans

set out to evolve a dense process for establishing shared meaning, and shared

norms, and supportive friendships and a strong sense of belonging to something

of great value.

It

is also about how the Residents found out

things about how society at large shuts down, controls and limits[9]

people and how they began taking back

agency in acting together for a better world.

The

founding director of Fraser House was Dr Neville Yeoman (1928-2000). The Unit

was exploring the evolving of non-drug community-based re-socialising

approaches within psychiatry (and without psychiatry) in Sydney, Australia

during 1959 to 1968.

A

concerted attempt has been made to make this E-Book understandable. One of the

challenges is that Dr Neville Yeomans’ Way was very eclectic, multifaceted and

guided by the moment in context.

Neville’s way can never be adequately expressed

in words. It can never be externalised.[10]

His

Way pervasively involves engaging the flux between internal and external realities, phenomena, and

experience within and between people – inter-subjectivity.

Yeomans’

Way is encapsulated in one of more than 1,000 poems he composed.[11]

The Way

is

searching

for the way

This

is one reason why this E-Book is not a step-by-step manual where the potency is

externalised and pinned down with words. Any attempt to do that looses the Way

Some aspects mentioned may appear paradoxical - though

these aspects are

typically at

different logical levels, where the term ‘logic’ is

used in an original

meaning – namely,

the pattern whereby all

things are connected.

Where typically a book may have

many sentences to state a good idea, many of the

sentences in this E-Book have a number of good ideas stacked in one sentence,

or sentence fragment. Sometimes just two words within a sentence embody a very

potent idea. This is consistent with Dr Neville Yeomans’ Way and the Ways being

explored in this E-Book

Some

sentences may need a few readings and some reflection, as like Alice, we are

going down the rabbit hole - perhaps to find a Wonderland.

ASSUMING A SOCIAL BASIS OF MENTAL ILLNESS

Yeomans evolved Fraser House assuming a social

basis of mental illness. This has links to the important role social cohesion

plays in preventing mind-body-spirit sickness in Australian Aboriginal culture.[12]

Regardless of conventional diagnosis, in Fraser House it was assumed that

dysfunctional Residents would have a dysfunctional inter-personal family friendship

network. This networked dysfunctionality was the focus of change. Consistent

with this, the Fraser House process was sociologically oriented. The Way was

based upon a social model of mental dis-ease and a social model of change to

ease and wellbeing.[13]

That the public at large never thought much about

social causes of dis-ease was discussed by Smelser in the BBC Series The

Century of the Self[14]

in speaking about the United States public post Second World War:

.......that they would in fact

adapt to the reality about them. They

never questioned the reality. They never questioned that it might itself be a

source of evil or something to which you could not adapt without compromise or

without suffering or without exploiting yourself in some way. So there was this

fit with the politics of the day

Yeomans

used a very holistic approach weaving together the biological aspects of the

physical body, the psycho-emotional aspects of people, and how everyone’s’

body-mind interacted with the social-life-world (the bio-psycho-social).[15] Yeomans was exploring

links between the social and the bio-psycho aspects of all. In drawing upon

sociological perspectives Yeomans included the Sociology of the Body and

Clinical Sociology – discussed later.

Yeomans

was interested in the re-constituting of the physical body moving in space[16] and how movement

interacts with the illness-wellness continuum; exploring moving beyond:

o feeling down (de-pressed)

o feeling heavy (with compressed vertebrae activating

kinaesthetic receptors through the spine increasing subjective sense of weight)

o feeling crushed,

o being on the back foot

o being off-side,

o feeing being bitter and twisted

Yeomans

was equally interested in Ways for re-constituting the body of the Fraser House Collective.

Yeomans said that he and all involved in Fraser

House worked with the notion that the Residents’ life difficulties were in the

main, from ‘cracks’ in society, not them. Yeomans took this social basis of

mental dis-ease not out of an ignorance of diagnosis. Yeomans was a government

advisor on psychiatric diagnosis as a member of the Committee of Classification

of Psychiatric Patterns of the National Health and Medical Research Council of

Australia.

Yeomans was familiar with twin sociological notions

that people are social products and at the same time people together constitute[17]

their social reality.[18]

Yeomans said[19]

that he took as a starting framework that people’s internal and external

experience,[20]

along with their interpersonal linking with family, friends, and wider society

are all inter-connected and inter-dependent.

Given this, Yeomans held to the view that

pathological aspects of society and community, and dysfunctional social

networks give rise to criminality and mental dis-ease in the individual. As

well, his view was that ‘mad’ and ‘bad’ behaviours emerge from dysfunctionality

in family and friendship networks.

This was compounded by people feeling like they did

not belong - being dis-placed from place and dislocated. Problematic behaviours

may be experienced as feeling bad or feeling mad, or feeling mad and bad.

While Yeomans recognized massively inter-connected

causal process were at work, he also recognized and emphasized this macro to

micro direction of complex interwoven causal forces and processes within the

psychosocial dimension.

Working with the above framework, Yeomans set out to

use a Keyline[21]

principle, ‘do the opposite’ to interrupt and reverse dysfunctional

psychosocial and psychobiological processes (biopsychosocial). That is, he

would design social and community forces and processes that would inevitably

lead from the micro to the macro towards Fraser House Residents reconstituting

their lives towards living well together. Yeomans told me a number of times

that the aim and outcome of Fraser House therapeutic forces and processes was

‘balancing emotional expression’ towards being a ‘balanced[22]

friendly person’ who could easily live firstly, within the Fraser House

community, and then in their new, expanded, and functional network in the wider

community.

Andy Brooker in an email wrote of:

Institutions promoting decontextualized forms of personal

responsibility - ‘often implying (through the veil of diagnosis) that the

person themselves, or their family are the cause of their problems; while

consistently failing to highlight the real cause of social harm and its[23] role in creating the

interlinking forms of oppression, at the root of their suffering.’

In

this view, dysfunctional behaviours may be seen as ‘defence patterns’, and as ‘the

best that people could do` in endeavouring to cope with and accommodate

societal pressures.

Fraser House took

people who were profound dropouts – people who were shutdown and largely disconnected from

society mentally and physically.

These were people who had had society

disconnect them from their friends, relatives, acquaintances, and society at

large by locking them up in prison cells and the back-wards in mental

hospitals. They had had ‘society’ ‘knocked’

out of them by the system. What had happened in their worlds had also happened

inside of them - people were dissociated[24] and dis-connected.

These residents had

profound shutdown in response to not fitting within the dominant system. Some

had the added overlay of addiction.[25] Fraser House was

originally called the Alcoholics and Neurotics Unit.

The aim in Fraser

House was to have these people engaging collectively in doing their own transforming of their own making

in dis-alienating and re-socialising

themselves so that they were not only able to cope, they were also able to live well with others and be resilient in the face of dominant system

pressures.

What Yeomans did do

was to constantly stack possibilities

for contexts to emerge where Residents engaged in their own transforming.

After leaving Fraser

House ex-Residents were able to live

well in Society. In many cases they became social catalysts creating social

innovation (rather than fighting the existing system or returning to being

‘dropouts’).

When

Yeomans was approached by me relating to doctoral research into Fraser House he

referred me to past staff, Residents, and Outpatients of the Unit, as well as

to Alfred Clark, the head of the Fraser House External Research team at Fraser

House.

He

and Yeomans wrote the book, Fraser House – Theory, Practice, and Evaluation of

a Therapeutic Community.[26] Alf Clark[27] went on to obtain his PhD[28] based upon his Fraser

House Research.

When

Clark left Fraser House he worked at the Tavistock Institute in the UK; then he

became Professor and Head of the La Trobe University’s very radical and

critical Sociology Department in Victoria, Australia for fourteen years.

He

was head when I completed my Social Science degree in his department – majoring

in Sociology of Knowledge.[29]

Clark

writes in his 1993 book, ‘Understanding Social Conflict’[30] that Fraser House and its outreach[31] is still the best model

for resolving social conflict around the

world that he has found.

None of these interviewees referred by Yeomans were able to shed any

light whatsoever on what actually

made Fraser House work. They could outline the timetable of activities - that

kept being altered by Residents in committee. They could confirm that Fraser

House processes did work extremely well and had good results in healing people

in an original sense of that term meaning to

make whole; to integrate. People did transform. This transforming was a

matter of degree - at times bit by bit, at other times big changes.

Interviewees confirmed that the Residents and Outpatients engaged in

mutual-help[32]

and self-help through being fully involved in re-forming their way of life together.

The interviewees could describe the many things that happened. However,

every one of them said that how all

this ‘worked’ and what made the processes work in being transformational was

‘beyond them’.

Yeomans was enriching practical

wisdom[33]

in the common person.

In a resonant way Postle[34] has introduced the term

‘the psyCommons’.

The psyCommons is a name for the universe

of rapport – of relationship between people – through which we navigate daily

life. It describes the beliefs, the preconceptions, and especially the learning

from experience that we all bring to bear on our own particular corner of the

human condition. To name these commonsense capacities ‘the psyCommons’ is to

honour the multitudinous occasions of insight, affect, and defect that we bring

to daily life: in parenting and growing up, caring for the disabled and

demented, persisting with the love that brings flourishing and success,

supporting neighbours visited by calamity, joining friends and family in

celebrations of life thresholds. As my colleague Andy Rogers described

it, the psyCommons is a rich resource of ‘ordinary wisdom’ and also, more

controversially, ‘shared power’. The air we breathe, the radio spectrum, the

oceans and the land we occupy – all these are commons, or ‘common pool

resources’; they belong to us and we belong to them. The psyCommons is one of

these commons. And, in parallel with the history of the enclosures of common

land in the UK and elsewhere, the psyCommons too has enclosures. In that

insidious way that politics can be invisibly present in daily life, the

psy-professions – psychiatry, psychology, psychoanalysis, psycho-therapy and

counselling – have enclosed the

psyCommons.

Yeomans Way at Fraser

House could be characterised in part by the notion of exploring all manner of

ways for enriching the psyCommons within

all attendees.

As pointed out by

Bob Dick:[35]

The harming

consequences of the dynamics of the larger system would have been also affecting

the Fraser House Psychiatrists and Psychologists (including

Yeomans). Their behaviour was also a consequence of system dynamics.

To quote the Biography on Yeomans

work life:

In the early days of Fraser House,

permissiveness within the staff-Resident relation was embodied[36]

in the slogan, ‘We are all patients here together’.

The self-help and mutual-help focus was supported by the slogan:

We are all co-therapists.[37]

However, recall that boundaries

were maintained between staff and Resident in that any staff needing

psychosocial support would either receive this within an all-staff support

group, or if the situation warranted it, the staff member would enter Fraser

House as a voluntary patient[38]

The following three paragraphs are repeated text (without

the footnotes – though you may want to refer back to these) from earlier in

this segment.

In writing and rewriting this E-Book I read through

these three paragraphs many times. Then it suddenly dawned on me that these

three paragraphs are the very heart and soul of Neville Yeomans’ Way. In many

respects they sum up the whole E-Book. Perhaps you, like me may get more significance

out of the repeat reading with interspersed comments.

Note that it reports Yeoman saying the following is

his starting frame work.

Yeomans said that he took as a starting framework that:

a) people’s:

a. internal, and

b. external experience,

b) along with their

interpersonal linking with family, friends,

c) and wider society

d)

are all inter-connected and inter-dependent.

Time and again we will be

referring to the following)

a)

the inter-play between

a. internal, and

b. external

b) the experience of all involved (again the mingling of the internal and

external aspects of experiencing)

c) Residents interpersonally:

a. inter-linking, and

b. inter-relating

d) with family and friends

(and learning about and experiencing belongingness and locatedness; and

expanding and enriching their sense of identity)

e) Re-connecting all involved

f) in new ways to society (new ways that are

functional and tapping the unique potentials)

Note this influencing is going

from micro – to macro; linking the individual to the group and the group to

society. Each of the above points are being done simultaneously; they are also:

a.

Inter-connected, and

b. Inter-dependent.

Given this, Yeomans held to the view that:

a)

pathological aspects of:

a.

society, and

b.

community, and

c.

dysfunctional social networks

give rise to criminality and mental dis-ease in the

individual.

Note the framing (dis-ease). Yeomans does not use dominant

system metaphors - ‘hygiene’, ‘health’ or ‘illness’ in referring to phenomena

of mind (mental)

As well, his view was

a) that ‘mad’ and ‘bad’

behaviours emerge from dysfunctionality in family and friendship networks.

This was

compounded by:

b) people feeling like they

did not belong - being dis-placed from place and dis-located.

Problematic behaviours may be experienced as:

c)

feeling bad or

d)

feeling mad, or

e)

feeling mad and bad.

While Yeomans recognized:

a)

massively inter-connected causal process were at work,

(going

from the macro to the micro – society to individual)

he also:

a)

recognized. and

b)

emphasized:

this macro to micro direction of complex interwoven

causal forces and processes within the psychosocial dimension.

Yeomans is referring to socialising, and particularly

in context, problematic aspects of, and consequences of societal socialising.

Working with

the above framework,

That is, the starting

with the framework that:

a) people’s internal and external experience,

b) along with their

interpersonal linking with family, friends,

c) and wider society

are all inter-connected, inter-related and inter-dependent

– a complex multi-variable system.

Dynamic transformational engaging with this inter-connecting,

inter-relating and inter-depending entails sensing everything as a complex

multivariable system. There is absolutely no way that this complex system can

be understood from an analysis of the parts. So many crucial aspects only emerge at the certain levels and kinds of

integrated complexity. For an example in nature - the property of sweetness

associated with glucose only emerges when carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen are

combined in a very particular way in very specific proportions (C6H12O6). You can analyse carbon,

hydrogen and oxygen separately and you will never find sweetness. Yeomans

Transformational Framework involved honing in on evolving inter-connecting,

inter-relating and inter-depending relational networking.

The living world with Fraser House was a Network of

Intersubjective Relating within Relational Networks involving networked

thinking. This concept is embraced by the German expression vernetztes denken

which translates as joined-up-thinking.[39]

Yeomans was a pioneer in linking ecology and social

ecology in using a living systems approach in engaging with people on the

margins. Living systems that are adaptive

and thriving well, while being provoked and challenged by the surrounding

ecosystem are usually in far from equilibrium states.[40] In complexity terms, every aspect of Fraser House was

structured by Yeomans and others to maintain the Unit in a far from equilibrium

state. When situations within Fraser House became stuck, Neville would

intentionally perturb it, and then use the evoked heightened emotional

contagion as emotional corrective experience. It follows that there multiple

ways to engender transforming in complex systems.

Yeomans set out to:

a.

use a Keyline principle (do the opposite)’

b. to interrupt, and

c. reverse

d.

dysfunctional

i. psychosocial, and

ii. psychobiological processes (biopsychosocial).

Yeomans is interrupting

society’s sustained socialising and reversing it by re-socialising all involved

in a micro-life-world of their own

making – where their way of life together

is wholesome and promotes ease (rather than dis-ease) and wellness in all of

its forms.

That is, he would design:[41]

e.

social, and

f.

communal

i. forces[42],

and

ii. processes

g.

that would inevitably[43]

lead from the micro to the macro

towards

Fraser House Residents reconstituting their lives towards living well together.

Yeomans told

me a number of times:

b) that the aim and outcome of

Fraser House therapeutic forces[44]

and processes was ‘balancing[45]

emotional expression’

c) towards being a ‘balanced

friendly person’

d) who could easily live

firstly, within the Fraser House community, and

e) then in their new,

expanded, and functional network

f) in the wider community.

There are a lot of ideas stacked in these three repeated

paragraphs. They came directly from my recording of Neville Yeomans telling me

stories about his days in Fraser House. And it was stories that I was hearing.

My retelling makes the words have overtones of explaining and

describing. Neville used the narrative form. I had written Yeomans words down

in the 1990s and added them to this E-Book without the denseness and import sinking

in. They were not some ‘introductory snippets’. They actually are succinct

dense statements encapsulating Yeomans Way.[46]

Margaret Mead the Anthropologist Visiting Fraser House

Margaret Mead the anthropologist visited Fraser House in the

early 1960s. Mead was the co-founder of the World Federation of Mental health

and the third president of that organisation during the years 1956-57. In August 1999, Yeomans was recorded as saying that

during that Fraser House visit, Mead stated that Fraser House was the only

therapeutic community she had visited that was totally a therapeutic community in every sense. Fraser House

anthropologist-psychologist Margaret Cockett confirmed what Dr Yeomans had said

about Mead’s comments.

By this term ‘total’ I sense Mead was referring to the

pervasively complex inter-connected, inter-related denseness of the

interweaving of every aspect of the

Unit’s densely inter-connected and

inter-related ways towards Resocializing and return-ing

Residents to living well in community. All

of my Fraser House informants also spoke of this dense holistic inter-related

‘total’ nature of Fraser House.

Maxwell

Jones the pioneer of therapeutic communities in the UK said of Fraser House:

......given

such a carefully worked-out structure, evolution is an inevitable consequence.[47]

Perhaps

Maxwell Jones (like Margaret Mead) could sense Resocializing (outlined in this

current E-Book) as being implicit in Clark and Yeomans’ book if one had

capacity to read between the lines and sense all of the rich implications of

Fraser House Ways, especially the inevitability of evolving.

Reframing Staff Roles

The Fraser House roles for professional staff

did not involve using their academic training – rather, the evolving and using

of a very different set of competences. For context, Yeomans profoundly respected the

psyCommons in everything he did. While the psy-professions generally had

totally enclosed the psyCommons of these potential

residents of the Fraser House (coming as they were from psychiatric hospitals

and prisons), Yeomans enclosed residents within Fraser House Commons and

regularly brought residents’ family friend network into the Fraser House

enclosure. Then via Governance Therapy and the Resocializing Program (see

later), Yeomans had all of the professional

staff stepping out of their

psy-profession roles (read experts ‘doing things to or for people’) to become

supporting the enriching of the psyCommons – as ‘healers’, (the term meaning

‘to make whole again’ – and enablers[48]

(a term meaning to support others to be able) – hence, supporting Residents and

Outpatients to do everything for themselves – mutual-help) in the context of

what Postle termed a 'universe of rapport' within relating between people.

Yeomans

wove together and adapted understandings from working with his father in

evolving Keyline, a process within sustainable agriculture. Neville Yeomans,

his brother Alan and their father P.A. Yeomans discovered ways to make nature

thrive.[49]

Neville

extended this work in exploring how to have human nature thrive. Neville used

bio-mimicry in setting up embedded contexts – the context within the context –

to multiple levels – and imbrications.[50] Within Fraser House,

Yeomans was continually setting up meta-contexts[51] and co-locating[52] people and things; as

well as combining[53]

people, things, and contexts[54] – the context for the

emergence of significant contexts.

Another

thing Yeomans was doing is perhaps summed up by the term ‘stacking’. He would

literally pile things on top of each other in a stack. He would stack each day

full of transforming possibilities[55] – something recognised by

Margaret Mead with her use of the term ‘total’.

Another

significant adaptation was engaging with indigenous understandings of the

geo-emotional and the links between land topography and social topography.[56]

Yeomans

said[57], that any psychiatrist

entering Fraser House would experience ‘their maximal career dis-empowerment’

as nothing in their academic training or their professional experience or

career to date would have prepared them for their new role of sustaining healing contexts; where all

involved - including all staff - were Resocializing

themselves by finding themselves

(their selves). As Maxwell Jones

observed, within Fraser House, evolution was an inevitable consequence – and this applied to the staff as well.

What’s

more, they would be working in an environment where Residents and Outpatients

who had already being involved in Fraser House living everyday and every night

for many weeks were far more experienced in Fraser House transforming ways than

these psy-professionals.

Residents

in writing one of the Fraser House Staff Handbooks[58] wrote:

So

you have decided to join Fraser House. Good career move!

The

Residents recognised firsthand the potency of this potential new area within

the psy-professions of having the role of being enablers of self-help and mutual-help within the psyCommons using uncharacteristic

community as the transforming medium (therapeutic community).

Yeomans said[59] that when staff returned to work everyone wanted to get the

latest news and catch up on everything that had been happening. So engaging was

the work that staff had to be sent home at the end of their shift; they did not

want to leave.

When I commenced this research

into Fraser House I assumed that some traditional

change process was being used. I would ask questions like, ‘what type of

therapy did you use’? Gestalt? Cognitive? Behavioural? The typical reply was:

It was not like that.

I

cannot pinpoint the time when I realized that in Fraser House ‘community’ of a peculiar and

uncharacteristic kind was the therapy and that ‘therapeutic community’ was the change process, not a just a name.

I

sense it came from conversations with a friend and colleague of mine, Dr Andrew

Cramb.

All

of the Resident Community Governance (refer later) and other ‘work’ by

Residents were change process. Everything was change process. Processes were eclectically spontaneous and not driven by

compliance with steps or theory.

Mead

recognised that with her use of the word 'Total'. ‘Community

being the change process’ was mentioned in the archives. However, I had just

not sensed it.

Once I had this understanding about socio-therapy and

community-therapy and that Neville viewed Fraser House as a complex

self-organising living system, it became clear that all that Neville had said

about his father’s interest in living systems was central and not peripheral.

One

of Yeomans’ mantras was:

Nothing

happens unless the locals[60] want it to happen.

There

is a dense subtlety to this mantra:

o The Residents

(the locals) had the say as to what, when, where, and how. This had the

processes always changing, largely by

input from Residents and Outpatients. Residents and Outpatients would play a

part in writing up the latest Staff Handbook, which was a catch-up depicting

what had already being put into

place.

o The collective was evolving their own Way of

life together, and it was the collective

that was Resocializing. Yeomans was never

engaged in Resocializing the Collective. It was never service delivery [61]

o Residents and

Outpatients were the one’s involved in helping themselves in self-help and

mutual-help

o They are the

ones doing the doing

o They are

collectively engaged, again, if they want to

o The foregoing

sets up the context for outsiders – staff - (working with some or more, or all

of the locals) in supporting locals to be able, or more able

o It presupposes

that any in the enabler role gain and sustain rapport

o For Yeomans, all

of the enabler language is in the passive voice. Everything is soft – never

imposing or directing – never ‘telling them what to do’ – rather, suggesting

possibilities – suggesting experiences

Yeomans did:

o

Set

up Fraser House as a purpose built infrastructure

o

Select

the staff

o

Set

up the intake process and the balanced intake of kinds of Residents

o

Set

up Big Group and Small Group Framework

o

Set

up the Governance Committee process that Residents and their family friend

network attended

o

Set

up tight constraints within Big and Small Groups

This replicates in a peculiar way that life

happens within constraints. Residents had come from psychiatric hospitals and

prisons that were filled with pervasive constraints.

In Fraser House, Yeomans set up a mini life

world[62]

with extremely tight socially ecological

enabling constraints[63]

that set up extremely attractive rich contexts for them to engage the mantra:

Nothing happens unless the locals

want it to happen.

Here we together evolve our reality, and as we

do this we may find ourselves finding our self, and enriching our self.[64]

Yeomans described his role as relational

mediator[65] between those involved

and life’s possibilities.[66]

Yeomans was involved in highly effective

sustained promotional activity. This is discussed later under, ‘Legitimating

Fraser House’. Yeomans typically had a waiting list of people wanting to attend

and or be residents at Fraser House.

Often, ex-Residents would be negotiating

re-entry for a further stay. And this context where people wanted to be

involved also applied to Yeomans’ outreach work where he was setting up micro

therapeutic community houses in Mackay, Townsville, and Cairns; he had no

difficulty obtaining residents.

In Fraser House the ‘locals’ were the Residents

and Outpatients. Yeomans applied the same mantra (Nothing happens unless the locals want it to

happen) during Fraser House Outreach up the East Coast of Australia, across the

Top End, and in his SE Asia Oceania work. The mantra embodies self-help and

mutual-help.

Upon

leaving Fraser House they were leaving the peculiar Fraser House Constraints;

no longer the daily round of activities. However, they now had internalized

Fraser House within them as re-socialized selves.

They

had an extensive repertoire of life competences; they had a new relating with

what things mean (meaning making) – and increasing wellbeing in their life with

others.[67]

They

could recognise themes[68]

and be aware of changing contexts,[69]

and new frames[70], reframes[71]

and new definitions of the situation[72]

relating to their relating to the

reality of everyday life.

This

world is rather crazy, not me!

Another

key component not yet mentioned was that Fraser House Residents in large part

went home on the weekends throughout their stay. This was a weekly reality

check on how they were transforming.

If

any had strife – call on your network of friends and acquaintances over the

weekend, or bring it up in a group on Monday.

The Sky is

Blue

Those

interviewed for the PhD said that they could not make any sense what-so-ever of

what actually made Fraser House

‘work’ in having people transform. While the people interviewed were still

working (or participating as Residents or Outpatients) in Fraser House in the

1960s, they had accepted Fraser House worked just like they accepted as a fact

that the sky is blue.

Yeomans himself stated that finding out how Fraser House worked was my research challenge; Yeomans knew how

it worked though he was not going to do my PhD for him (or for me).

Neville never described Fraser House to me or attempted to explain it in

any way. We discussed the limits of explaining and describing many times. In

summary:

‘Explain’ means to make (an idea or situation) clear to

someone by describing it in more detail or revealing relevant facts (facts are

slippery and depend on human interest).

The Romans realised that explaining

involved an abstracting process – the leaving out of the richness of the

original.

The word explain is derived from ex- a word-forming

element; in English meaning usually ‘out of, from’ - from the Latin ex ‘out

of, from within; from which time, since; according to; in regard to’. Explain

is also derived from plain - ‘flat,

smooth’: from the Latin planus ‘flat, even, level’. In combination ex-planus literally meaning ‘out of the plain’ (out of the

two-dimensional); that is, reducing the multi-dimensional to two dimensions.

Yeomans was very wary of explanations (and the inadequacy of ‘describing’).

In place of explaining and describing Neville told stories and told me

to ask my interviewees to tell their stories. He told me to visit Fraser House

building and personally sense the place. He also teed up many contexts of

similar form and therein created contexts for me to experience things of great

potency.

The PhD has been completed[73] and revised and extended

as a biography[74]

on Dr Neville Yeomans’ life work. This Resocializing E-Book has been written as

a stand-alone piece, although reading the Yeomans biography and other

references may enrich understanding.

An associated text, ‘Coming to One’s Senses – By the Way’[75] provides scope to

complement understanding.

This current E-Book also draws upon:

o Berger and Luckmann’s, ‘Social Construction of Reality - A Treatise in the Sociology of

Knowledge’ (1976),[76] and

o Pelz’s, ‘The

Scope of Understanding in Sociology - Towards a More Radical Reorientation in

the Social and Humanistic Sciences’, and

o Clinical Sociology[77]

to explore some of the essence of Fraser House

Re-socializing Ways.

Setting

out in words how Fraser House worked is a near impossible task. You had to be

there. You had to experience it. In fundamental ways words are inadequate.

Words are used sequentially. Sentences are also sequential. Fraser House was

fundamentally a profoundly dense, interlinked, integrated, holistic process. So

much was happening below awareness. So much was happening simultaneously. There

was constant Flux and Flow. There was continually stacked framing, reframing,

functional boundary ambiguity and co-locating of multiple realities.[78] Sometimes the

participants were all together. Sometimes they split up and were in anywhere

from two to eighteen rooms, or scattered throughout the facility.

All

were engaged in this splitting up and re-joining – what Yeomans’ termed

cleavered unity.[79]

What

was happening in different places also had multiple implications for others

involved. So much was laden with multiple implications.

Masses

of significant and potent things were constantly happening

day and night, day in and day out, with multiple things happening at the same

time in the same place every moment – in a word ‘dense’ and in another ‘total’.

In Fraser House, often what was potent was the most simplest of things.[80] And these significant and

potent things were indelibly linked to place – such as the Big Group room.

Yeomans was hyper-aware of the significance of place and Ways to add to and

enrich the significance of place. He stacked significant happenings inside the Big

Groom room. With ‘place’ looming so large Yeomans was well

aware of what has been termed the method of loci (loci being Latin for

"places") – this is a method of memory

enhancing which uses the phenomenon of knowing linked to place and the

associated spatial memory and visualizing linked to the use of familiar

information about place and one's spatial environment to quickly and

efficiently recall information and re-access psycho-emotional resource states.

Happenings within the Big Group room were readily recalled and along with this

recall; the accessing of psycho-emotional resource states accompanying the recalled

experience. Attendees would re-access these resource states whenever they

re-entered the Big Group room.

The

challenge in this E-Book is to have the reader reading the sequential material and progressively receiving information that

has the quality of being ‘stacked’, while shifting beyond ‘stack’ to receiving

the feel and sense of this non-linear dynamic – to sensing the whole-of-it[81] and beginning to get it –

whatever it is. Not your average

academic or non-academic read.

All

involved in the uniqueness of Fraser House as a social system had embodied

experience leading to embodied knowing (typically without the knowing making

much sense) and also to actual transforming (and hardly noticing the difference

– so they did not sabotage their change work) and to moving back to living more

easily in wider society.

Yeomans[82]

suggested that a starting point for PhD research on Fraser House was reading all

of his father’s writings about agriculture.[83]

Yeomans then said that he had extended

the work that he had done alongside his father towards having nature thriving

by adapting ways from nature[84]

to fostering human nature to thrive. At the time this suggestion made little

sense to me. My own preconceptions about what Neville and his father were doing

was massively limiting both my inquiry and my perception and it was many months

later that I did follow Neville’s very sensible suggestion. Without a sense of

the profound linking between nature and human nature and how Yeomans was using

bio-mimicry to evolve his processes one would never plumb the depth of his Way.

Recall that those interviewed for the PhD said that Fraser House was

incomprehensible – to repeat, they had accepted Fraser House worked just like

they accepted as a self-evident fact that

the sky is blue; Fraser House was just there, like the AMP Society[85] - as part of the ‘nature

of things’. The term ‘reify’ applies. ‘Reification’ is the treating of human

phenomena as if they are natural or ‘god-given’ and not human-made and socially

constituted. Fraser House phenomena were legitimated by their very existence as

‘something in the world’. In this context, both the AMP Society[86] and Fraser House were

reified. This process tends to hide the fact that because these institutions

are made by humans they can also be re-made by humans; they are not fixed in

stone. While this incomprehension was going on among my interviewees back in

the 1960s (and still continuing when I interviewed them in 1998 and 1999),

everyone involved with the Unit during the Fraser House years was continually

immersed in the very processes that constituted Fraser House, namely collectively re-constituting their shared

social reality, while simultaneously, all

were individually and collectively being re-constituted by this same social

reality.

While

looking at reification at the institutional level, the same process can happen

to both roles and identity of self and others.

Reification concretises such that the person becomes the role and nothing more.

The distance between the person and the role shrinks. This same reifying process

had contributed to Fraser House Residents’ way of being prior to, and during their incarceration in mental hospital

or prison – they were those types of people. At that time this typing of these people was accepted as

fact by ‘Authorities’:

A

person diagnosed as thing – she’s a neurotic (she IS a neurotic).

She

is here to be contained (in multiple senses) and looked after – not transformed

beyond assigned typing; to be ‘warehoused’ indefinitely and not to be returned

to society.

Similarly,

these ‘mad’ and ‘bad’ had totally identified

with this socially assigned typing

(typification). In self referential description, some were mad types; some were bad types; and some were both mad and bad types. In Fraser

House they began changing the type of people that they were, and sensed they

were.

Herbert

Mead wrote:

A

self can arise only where there is a social

process within which the self has had its initiation. It arises within that

process.

Many

of the Residents when they arrived at Fraser House were ‘no-bodies from

no-where’. Fraser House evolved a very special social process where the

Residents’ selves could have initiation and arise.

Fraser

House was collapsing old dysfunctional reifications at both role and identity level. Self was

being enriched so that Residents began realising their capacity to take on new

types of roles and maintain distance between their various roles and their core self. They became types in the

process of transforming type; being involved in Self realising.

Here

is more of Herbert Mead’s comments on the self:

A

self can arise only where there is a

social process within which the self has had its initiation. It arises

within that process. For that process, the communication

and participation to which I have

referred is essential. That is the way in which selves have arisen. There the

self arises. And there he turns back upon himself, directs himself as he does

others.

He

takes over those experiences which belong to his own organism. He identifies with himself.

What

constitutes the particular structure of his experience is that what we call his

‘thought’. It is the conversation which goes on within the self. This is what

constitutes mind (my italics).[87]

Outside

of notions of type assigned by others, Residents and Outpatients began refining

and fine-tuning their selves in becoming a fine[88] self[89]

All

involved were learning how to be self-made people and collectively-made people

of high worth through high quality mutual-help and self-help while tapping into and evolving their unique potentials

(refer, ‘Realising Human Potentials’).[90]

At

the same time they were taking on the understanding that:

Here

in this Unit, this is what does

happen for all involved, and that

this changework is our primary role,

and that we only have twelve weeks to do all of this, with all the support we

will need, so we can get on with it now.

Fraser

House existed as both an objective

and subjective reality. People could objectively see and hear it in action.

They could also experience it internally

as a subjective experience.[91]

What

made Fraser House work will be explored in terms of externalization, objectivation, and internalization.

Fraser

House way was exploring processes for the ongoing modification of subjective reality.

Residents

and Outpatients were continually having experiences within powerful contexts

that were altering their internal psycho-emotional and physical states of being

in everyday life.

Little

known and apparently not discussed was the fact that they were also

transforming the way they moved their bodies – the way they sat, the way they

stood, and the way they walked.[92]

While

starting as an idea in Yeomans head, Fraser House became an objective reality; an entity existing in

the externally real world. It became, by various processes, there present to

visit and see on Cox Road in North Ryde on Sydney’s North Shore as an

objectively present complex.

People who

participated at Fraser House were constantly engaged in continual exchange between inner and

outer experience.[93]

They were internalising their experience of

the Unit. These processes of externalization,

objectivation and internalization

were not sequential; rather they were all occurring simultaneously as Fraser House evolved. Everyone involved was also

simultaneously externalizing their internal experience of being in Fraser

House while internalising their

experience as an objective reality. Internalising was evidenced by objectively observing Objective

behaviours and deep immersion in intersubjective relating, while flitting

between inner and outer focus is an inherent aspect of the human condition. To use a metaphor, living in Fraser

House was like living in a fishbowl surrounded on all sides by participant

observers who showed sustained interest in you.

All involved

were ongoingly mutually identifying

with each other in a two-fold sense – firstly, as ‘people involved with Fraser

House’; secondly, in this they were also identifying their own identity in the

process of their transforming. In identifying with Fraser House they were

reforming (re-forming) their own identity. They not only shared this

experience, they participated in the experience of each other’s being.

Together they continually

re-constituted these phenomena – the objective reality of Fraser House. They

became significant in each other’s lives. They became significant others.

Many significant

others became guides and mentors into this strange new reality.

These mentors

were one significant representation

of the Fraser House plausibility

structure in the various roles they played; this process was one way

whereby this new reality was mediated to the new arrival.

The

Fraser House process was clearly not insight-based. Knowing theory was not

required. The processes and the experiences and the meanings and understandings

derived from deep immersion in the lived-life experience of Fraser House were

all pre-theoretical.

To

repeat, when interviewed in the 1990s, no staff, Resident or Outpatient had any

idea whatsoever about what made Fraser House Work. This was also admitted by

Professor Alf Clark who was the head of the Fraser House External Research

team. Clark co-authored with Yeomans the book on Fraser House.[94] That book detailed the

Theory, Practice, and Process of Fraser House. However that book gave no

indication whatsoever as to what would have made such Theory, Practice, or

Process work. Professor Clark went on to be head the Sociology Department in La

Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia for fourteen years.

Perhaps

Clark was looking at Fraser House through the framing filters of psychiatry and

psychology such that he never sensed the potency of the sociological framing or the (here we evolve our own way of life

together; our own culture) anthropological framing within Fraser House. Or

perhaps he too was always being swept up in the dynamic experience of Fraser

House.

Some

dynamic was going on that limited his understanding. One big one - people tend

to not notice socialisation in everyday life and yet it is pervasively present.

Recall

that Residents at Fraser House had had socialisation ‘knocked’ out of them.

Fraser House Way was Resocializing them.

This

Way extended to the whole-of-it;[95] the bio, the psycho, and

the emotional aspects. The Way was supporting them all to evolve their own way

of living well with themselves and each other – their way of life. They were

evolving their own culture, in ways supporting enculture.[96]

Yeomans,

in pioneering therapeutic community in Australia was engaging all involved in

evolving a very uncharacteristic community with processes that led to the

emergence of densely interconnecting, inter-relating, inter-depending,

inter-woven aspects conducive to transforming. Fraser Houses, as therapeutic

community, had community (of this

unique kind) as the therapy (wellness change process).

What

was happening was experienced and internalised as subjective bio-psycho-social

embodied experience.[97]

One

resource that came out of the PhD is the Method Section[98] especially aspects

relating to connoisseurship and contemplation in qualitative method that

informed this current E-Book. Another is the paper, ‘The Art of Seeing -

Interpreting from Multiple Perspectives’.[99] Another resource for

making sense of this E-Book is the Natural Living Processes Lexicon – Obtaining

Results with Others.[100] Another more general

resource is Realising Human Potential.[101]

It

is suspected that Dr Yeomans did know at the level outlined in this E-Book, though

passed on nothing to the others involved; and didn’t pass on such knowledge to

me. No knowledge of theory was needed or

required to make the Fraser House Social System work. Yeomans’ experience

was that Fraser House worked because of what was experienced by everyone involved, staff included.

Thinking,

especially thinking about experience interrupts experiencing experience.

Thinking disconnects people from feeling.[102]

The

Fraser House processes had everyone immersed in being aware and emotionally responding

to the moment-to-moment unfolding action, not distracted by being inside of

themselves up in their front brain mulling over theory, or using theory to

sabotage their own and others’ change work, or theorising other people to

everyone’s utter distraction - thinking

driving one to distraction.[103]

Things

happened extremely fast in Fraser House, and all involved stayed present in the

moment. It was reported that the rich energy even had catatonics coming back to respond to what was happening.[104]

In

Fraser House, exploring re-socialising through

social relating was an aspect of the approach. Like that last sentence, the

passive voice form was typically used by Yeomans when he was speaking. He said

that the passive voice softened things as it was less imposing.

Typically,

people arrived at Fraser House with a dysfunctional family-friend network of

five or less. Prospective Residents were required to sign on ten times as an

Outpatient and attend Big Group[105] with members of their typically

dysfunctional family and friend

network also signed on as Outpatients - and all stay for Small Groups.[106] After these attendances

prospective residents may be accepted to become a Resident as long as their

family friend network members committed to continue regularly attending as

Outpatients throughout the Resident’s stay at the Unit.

Because

of lots of integrated processes Residents

left after being in Fraser House for twelve weeks typically with between 50 and

70 people in a now functional family-friend network. These network members also

had a common experience of Fraser House Big and Small Groups.

After

Residents had been in Fraser House for a time, the people who were now in

Residents’ expanding family friend networks were people they were now in close

regular contact with, with varying degrees of emotional closeness and emotional

dependency in the process of transforming to emotional independency. After

leaving Fraser House, Residents could and would attend Fraser House Big and

Small Groups on a regular basis as Outpatient friends of those still in Fraser

House. Additionally, Fraser House Residents could be accepted for up to three

further stays at Fraser House. These processes extended and maintained their

connecting with Fraser House.

Another

key aspect of Fraser House Way was throughput. Fraser House had a continual and

dynamic streaming of people coming into and leaving with those in the process

of preparing to leave with highly evolve Ways passing these on to new arrivals.

People identified

each other and in so doing identified

themselves – as in, enriched their own identity

and sensing of their own self

identity.

For

all involved, Fraser House was there as a ‘self evident compelling reality’. It

was an enclave (closed society) bracketing off the outer world. While before,

overpowering life-at-large was the paramount

reality, upon entering Fraser House, the extraordinary richness of the

Unit’s processes becomes the new paramount

reality. Like the rise and fall of the curtain marks the beginning and end

of the play reality, after Fraser House had been going for a few months any new

arrival would quickly sense that this Fraser House reality was a very different

one to anything they had every experienced before, especially after learning

they had being assessed by a very competent assessment team who were now to be

their fellow Residents.[107] And then finding out these

very assessors had arrived at Fraser

House not long ago with a diagnosis that could be translated as ‘mad’ and/or

‘bad’ [108]

Then

going into the intensity of the first Big Group. All these unusual things were

markers[109]

for this new and extraordinary reality.

Fraser

House was structured by Yeomans as an INMA

- an Inter-people Normative[110]

Model Area. In this context, ‘Area’ has the connotation of place and space –

firstly, a ‘Locality’ – meaning connecting to place, and secondly, a ‘Cultural Locality’ meaning a place where people become connected

together connected to place – in this case, Fraser House.[111] The term ‘enabling

environment’ also applies to Fraser House; where a physical and emotional

(geo-emotional) environment is evolved and sustained where every single aspect

supports all involved to be more able in tapping into and using their unique

potentials.

Exploring

values and norms was a core focus. Yeomans carried out extensive values

research comparing values held by Fraser House Residents and Outpatients with

over 2,000 respondents in Melbourne and Sydney, the largest research study of

its type in Australia at the time.[112]

Yeomans

did not publically use this INMA term in the sixties, though he had the idea of

an INMA and used the idea of ‘model areas’ in his work in normalising culture.[113]

This

may be the place to introduce Neville Yeomans bio-mimicry of the work he did

with his father in evolving sustainable agriculture.

On

their farms the Yeomans supported nature’s naturally occurring self-organizing

processes;[114]

in particular through tapping the freely available potential energy in complex

systems.

Yeomans

used to engage the free energy rather than struggling to fix the stuck energy.[115]

As

an example, Yeomans’ outreach work that he commenced in 1971 in the Atherton

Tablelands in Far North Queensland continues to this day as a self-organizing

social system after his death in 2000.[116]

All

involved in Fraser House would meet, engage and relate with each other in an enabling

environment[117] bracketed off

from mainstream.

They

would explore as differing types –

initially, types deemed to be deviant by authorities within the mainstream

system, and radically affected by the pressures of the mainstream life.

Residents

would arrive at Fraser House typically with one of two particular types of

sympathetic-parasympathetic tuning:[118]

Either:

A.

Under-aroused,

under-active, over-controlled, and

over-anxious

or

B.

Over-aroused,

over-active, under-controlled, under-anxious, talkative, and noisy

Within

these two particular types there was a whole typology of sub-types of actors.

Types of behaviour quickly became a function of context.

Dr

Yeomans was a member of the Committee of Classification of Psychiatric Patterns

of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. In such a

role he well understood psychiatric diagnostic typing though did not use

diagnosis within Fraser House.[119] Notes in Resident

Progress Records would not distance Residents by using impersonal

categorising/descriptors (she IS a psychotic).

In Fraser House, Resident file notes contained

comprehensive life histories, gathered by the Admitting/Assessing Group and the

Progress Group and as an integral aspect of Psycho-Social Research within the

Unit. File-notes were extremely relational - personal, inter-personal,

biographical and containing notes relating to changes in the living experience

of social relating as a type-of-person-transforming-type. Example: ‘Name of

first primary school teacher’ - useful for age regressing to re-access

psycho-emotional resource states.

In telling their own story they are hearing themselves speaking

and recalling past experiences and identifying with these memories, and in this

identifying they are also enriching their own identity (identifying themselves)

and seeing and feeling their lives emerging as having greater meaning and

purpose especially that of supporting and helping themselves as they are supporting

and helping others.

Yeomans

took in new Residents on an intake balanced in many respects:

o Ensuring that there was a balanced spread of people

with the differing mainstream diagnostic categories[120]

o Gender balance

o Half under-aroused and half over-aroused

o Half under-controlled and half over-controlled

o Half under-anxious and half over-anxious

Within

Fraser House everyone apprehended each

other within a typificatory continuum as a type-in-the-process-of-changing-type.

Two

of Type A[121]

were placed in same sex dorm with two of Type B so there was a natural pressure

to move towards a more normal centre; the more aroused becoming less aroused

and vice versa, with similar shifts in the other aspects.

Photo 1 One of the Fraser House Dorms

Typically,

new arrivals found Fraser House to be a massive improvement compared to where

they had been.

They

had the choice of returning to where they had been, or going along with the

norms of this new place. The report from those involved was that Residents

participated and engaged in all of the processes. Every aspect of day-to-day

life in the Unit was somehow ‘massive’ and ‘compelling’.

Some

many of the aspects of the way Fraser House was composed[122] was attractive – it

attracted people. Many people wanted to attend as visitors.

Residents

at first apprehended others and increasingly comprehended others as different,

though specific types within a

dynamic reciprocated typificatory schema.

Simultaneously, types would be

socially re-constituted in typical (typified) ways in the Fraser House typificatory schema.

The

layout of Fraser House (refer diagram below) meant that Residents were

constantly meeting fellow Residents and relating. There was one long corridor

and enclosed pathway running through the Unit. Chilmaid, a Fraser House psychiatric

nurse during the 1960s was one of my interviewees for the PhD. He stated that

during the day when no one was in the upstairs dorms, on a walk from one end of

the Unit to the other when people were outside of activities and generally

milling around before or after dining you would meet or see everyone in the

Unit.

Typically, Residents were continually being present in

social relating. If people were deep inside, others would attract their

attention. This continual passing of each other and engaging in activities set

up continuous verbal and non-verbal reciprocity within expressive acts.[123] A lot of this ‘expressive

language involved what may be called ‘speech acts’,[124] where the

speech is more than an utterance; the speech is an act with transformative consequences.

An example of a speech act

from another context is the words of the marriage celebrant, ‘I now pronounce

you husband and wife together’.

Relating

Well was ‘continually been held up’ as ‘this is what we do here. We all stay

attending to social relating.’

Residents

in face-to-face contact were simultaneously available to each other. The

‘other’ was in many ways ‘more real

to me than I am.’

To

reiterate, this enhanced typical

apprehending of each other was in a two-fold sense.

Within

the concentrated reality of everyday

Fraser House life there was a continuum

of typifications where, in moving through Fraser House everyone would apprehended; then after a time they

would begin comprehending each other

as a type-in-the-process-of-changing-type.

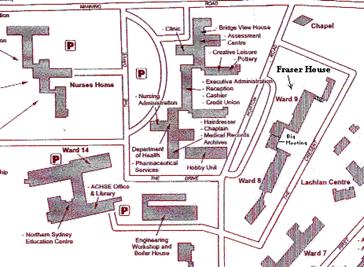

Diagram 1 Map

of Section of Gladesville

Macquarie Hospital

Showing Fraser House as a Set of Six Buildings ringed by roads on the near

right with a Long Pathway from One End to the Other

ROLE

TAKING

By

being involved in activities in the Unit, the Residents and Outpatients

participated in the objective reality

of the Fraser House social life world, or to use Benita Luckmann’s term, a

‘small life world’[125]. Residents gained

experience, confidence, and competence in taking on the various roles within

Fraser House. By internalising these roles, they (the roles) become subjectively real to participants.

Residents had the objective experience

of participating. They could take on the idea:

I

am the person doing these roles at Fraser House, and others are confirming I am

doing them well.

After

a time, doing these various

roles became natural, automatic, habitual, hardly noticed, and rarely or never

questioned.

All

of this helped constitute the objective

reality of life in Fraser House, and with this, the reciprocal typifying

comes to have the quality of objectivity.

While

initially, objectivity may be tenuous, the density of the interconnected tasks,

roles, and social actions ‘thickened’ and ‘firmed up’ objectivity.

Now

we’re going to have Big Group......

soon

becomes:

This

is what we do around here.

This

life together starts to be defined (determined with precision) by a widening

sphere of taken-for-granted socially

ecological normative habitualized routines; this in turn sets up the

possibilities for division of labour

and the adopting of tasks and roles requiring and demanding Residents

and Outpatients use a higher level of

attending to what is going on in their respective roles. One attendee of

Yeomans groups stated in writing about Yeomans processes:

They

were good for different people in different ways. It intensifies communication,

that’s what it does. It focuses you. You get down to the specifics of social

and cultural communication rather than just, ‘how’s the weather’?[126]

Residents

and Outpatients who have become competent in a specific task and associated

roles were given the role of mentoring new people to take on these tasks and

roles on the principle:

Here

all tasks and roles are passed to those who cannot

do them so they can learn to do them well with support.

These

roles and role-specific tasks help constitute particular types of relevant being[127]

and action within the continuing role-specific

social action situations. Roles are types

of action by types of actors in such contexts. Further, Fraser House roles

represented themselves. For instance, helping represents the role of ‘helper’.

These

reciprocal typifications were being constantly re-negotiated as people were

transforming in the face-to-face ever-changing located situations where they

were negotiating meaning[128] (Big Group, Small Group,

Governance Committees, etc).

Having

transitory processes that were

being constantly modified by Resident and Outpatient driven community action

was an essential element of the reality of everyday life in Fraser House.

Fraser House as institution itself

typifies individual actors and their actions. All involved begin ‘taking

on’ the Fraser House Way. The institution posits (puts forward as fact) that actions of

type X will be carried out by Residents of type Y. ‘Once you have been here for

a while you will be on the governance

committees and doing social research etc.’

The

helping Resident is not acting on his own, but as helper. Residents were identifying

with these roles, and internalizing

this identifying in enriching and

expanding their own self identity.

Additionally,

the helper role is one part of a dense woven tapestry of roles making up the

conduct of Fraser House Residents – for instance roles such as: assessor,

audience, crowd, mediator, negotiator (especially supporting self and others in

negotiating meaning) role model, facilitator, innovator, researcher, carer,

catalyst, paraphraser, and exemplar.

In

Fraser House there was the continual exploring, trying on, negotiating,

navigating, and experiencing of roles and role-specific behaviours. In any of

these roles the Resident acts as a significant representative of Fraser House.

Later

Yeomans extended his use of roles in Resocializing to setting up what he termed

hypothetical realplay.[129] Participants become

involved in taking on roles (and role specific behaviours) in potent

hypothetical contexts that are very real in their consequences for transforming

with others.

Fraser

House Residents, Outpatients, and all staff were together continually

re-constituting the communal and social reality of their life together in

community. That process was folding back to be individually, socially, and

communally reconstituting firstly, everyone’s being (being-in-the-world) with their own outer and inner states of

conscious and non-conscious experience of their phenomenal experience of their being in the world

with others, and secondly, reconstituting their being-in-the world with others in the

Fraser House extended transitional community, and in this, together constituting their Fraser House social

life world.

Constituting Fraser House as an Institution

The

increasing set of Fraser House roles evolved from the same processes that constituted Fraser House as an institution -

through the internalising of socially

ecological[130] habitualized routines that had been objectified

as routines that could be observed objectively on a daily basis.

As the functional in context was always highlighted, the continual pressure was

towards quality acts – embraced by the Greek term phronesis meaning wise practical acts. These routines also embraced

and constituted tasks and roles that represented and re-presented the Fraser

House institutional order. All conduct by all involved in Fraser House was being

constituted[131]

by these social processes. The roles of Fraser House had a similar constituting

power as every other aspect of Fraser House. This is a reflection of the total nature of the interweaving of

processes within this Unit that Margaret Mead described as total.

While

in one sense Fraser House was a set of buildings on the grounds of Macquarie

Psychiatric Hospital, the human face of this

institution manifested itself[132]

and was represented and re-presented in interacting performed roles. This

was one way Fraser House manifested itself in

human exchange and experience.

Fraser House as institution

soon had its immediate past as history

and the Unit’s transforming processes were being informed by this history that

lived on as repeated stories passed on within Fraser House gatherings and

networked exchange outside of Fraser House. These stories were relived and shared in storytelling when ex-residents and

outpatients got together both inside and outside of Fraser House.

These glimpses of shared experience were framed in story

form and were living on as biography and recallable memory among those involved.

Yeomans in his young life lived with his family among

remote area aboriginal people[133] living traditional

lives and he experienced firsthand the potency of repetition of narrative for

social cohesion and community wellbeing. Narrative therapy was an integral

aspect of Fraser House Way and was a core aspect of Fraser house Research.

While all involved co-constituted Fraser House as

Institution, the institutional framework[134] set limits and

constraints on people that were of their own

making. These limits and constraints set up a framing of contexts (Big Group,

Small Group, Governance Committees and the like) for establishing new patterns

in habitualized conduct leading to transforming in many ways.

Fraser House as Institution was operating at the level