UN-INMA PIKIT FIELDTRIP REPORT (REVISED)

Post Emergency Situation Report

On Community Psychosocial Resources,

Resilience and Wellness Processes

SEA-EPSN Field Trip to Post War Zone in

Pikit, Mindanao, Philippines

13-19 November 2004

Written April, 2014.

Consistent with the notion ‘rapid

assessment’, this report from UN-INMA was originally available to the

Secretariat within 14 hours of return

to Manila from the war zone around Pikit in Mindanao in Philippines in November

2004.

Interim Reports were sent within three hours of arrival and then twice a day

during the Field Trip.

This Revised Report follows the Rapid

Assessment of Disasters Proforma reviewed at the Tagaytay Gathering in 2004.

Personal Reports of other Field

Trip Members may vary considerably from this Report, in part from issues raised

in this Report.

This revised version is an Extended

UN-INMA Report with later reflections added.

A Team Synthesis Report was later

submitted to the Secretariat by one of the Team Leaders a number of months

after return to Manila. UN-INMA never received a copy of this Team Synthesis

Report.

Resonant Links:

o Rapid Assessing

of Local Wellness, Psycho-Social Resources & Resilience Following Disasters

(RAD)

o

Preparing for and Responding Well to Disasters - PRWD

o Recognising and

Evolving Local-lateral Links Between Various Support Processes

CONTENTS

Frameworks for Field

Trip Action

After briefly stating the team’s mission

and meta-mission, there’s a UN-INMA Rapid Assessment Situation Report on the

Pikit context based upon the Tagaytay Assessment Proforma, followed by a UN-INMA process review of the

briefing and functioning of the SEA-EPSN TEAM during the Pikit, Cotabato,

Mindanao Trip 13-19 November 2004 covering what worked well and major shortcomings relating to the

mission.

FRAMEWORKS FOR FIELD TRIP ACTION

Prior to giving

the Situation Report, this document specifies the following frameworks for

field trip Action:

o

The Framing Ultimate Purpose

(Meta-Mission)

o The Field Team’s Mission

o The Framing of Support Action

o The Framing of

SEA-EPSN Reports

THE

FRAMING ULTIMATE PURPOSE (META-MISSION)

From the Secretariat Pre-trip Briefing, the Field Teams ultimate

purpose was fostering possibilities and opportunities for local people to mutually engage in their own ways of being

and acting together towards expressing and enjoying their own rich integral

wellness states through mutual-help.

Also from that Briefing, the Field Team’s purpose was guided by values of respect for community-self

determination of their own cultural and spiritual life ways.

It later emerged that some of the Team members, not at the Team

Briefing in Manila did not share this Framing Meta-Mission.

THE FIELD TEAM’S

MISSION

From the Briefing,

our mission on this field trip was to:

o Provide

psychosocial support to the self-help and mutual-help actions of the people of

Pikit in their post emergency contexts (some

team members did not see this as the team mission)

o Prepare a

situation report on the protracted emergency in Pikit for potential use by

outside aid organisations including local NGOs and CBOs

o Pre-test and

report on SEA-EPSN Emergency Response Guidelines, Proforma and Resources (some team members did not have any

knowledge of or familiarity with the Guidelines, Proforma or Resources)

o Support the local

NGOs and CBOs

o Create a model

Case Study Post Emergency Situation Report for:

o including in the resources

o for distribution

among SEA-EPSN members

It appears that some team members did

little to contribute to writing a situation report. Any feedback from some of

the team members seemed to be primarily a critique of the UN-INMA member. The

UN-INMA team member was never sent a copy of the final Situation Summary

submitted months later by one of the team leaders.

o Realplay, evolve

and report on Emergency Team functioning in the field

The SEA-EPSN field

team recognises (?) that:

o

Going into emergency contexts is a growth

challenge (some team members did not

recognise this)

o

Engaging in actions focusing on achieving the

above mission in emergency contexts typically stretches members beyond current

competencies

o

Apart from sources of stress emerging from

the emergency context, interpersonal stress in the team may flow from

experiencing others engaged in adaptive

mission-based action beyond the stressed person’s’ experience, as well as from

the team engaging in discomforting personal and interpersonal growth rather

than retreating to defensive harmony maintaining the status quo and current

performance – team growth takes people beyond their current comfort level and

beyond their traditional domains of competency (some team members were not the least interested in personal or team

growth)

That some members of the team were not on

board with the team’s mission (and neither were the local NGO people in Pikit)

influenced the outcomes and reported outcomes of the Field Trip and team

members comments on their fellow team members.

THE

FRAMING OF SUPPORT ACTION

1.

Experience in the Region has demonstrated,

given appropriate contexts, the efficacy of:

o Respectful gentle

caring presence

o Attending and

listening

o Cultural

respectfulness and sensitivity

o Community-based

normalizing action

o

Supporting of the local natural nurturers

and the local ways for reconstituting wellness – ceremonies, rituals, and the

like

o

Sharing micro-experiences gathered from

the Region if the locals want; this may increase local people’s capacities for

return to wellness

2.

We ensure that all action is in keeping

with local culture and way.

3.

Local NGOs may give guidance

4.

Having, wherever possible, the community

or communities making the decisions, using, as much as possible, their normal

decision-making or other agreeing processes about things like the layout of

camps, places for and of worship, schools, play areas, basic rules for local

governance of the camps, and the like – locals

reconstituting local normalising

governance

5.

Providing enabling support for internally

displaced people, refugees and others effected by man-made and natural emergencies

so they may be involved in substantive mutual benefit action such as:

1) camp set-up and

organization

2) local camp

governance

3) family, friend and

community reunion, and

4) food distribution

6.

Reconstituting some, or all aspects of

schooling and other everyday life experience for children - creating safe

child-friendly spaces

7.

Identifying and supporting the continuing

of existing wellbeing activities, as well as supporting the commencing of

normal everyday activities that locals have not yet reconstituted among the

communities affected by the emergency - within camps and informal and formal

settings

8.

Fostering and supporting cultural healing

action and re-creational activities for children, adolescents and adults as an

aid to increasing wellbeing: play, artistry in all its local forms - painting,

puppetry, drama, theatre, dancing, music making, sculpture, storytelling,

singing, chanting, dance, celebrating, and the like

9.

Respectfully supporting and fostering the

reconstituting of cultural and religious happenings, rituals, ceremonies,

celebrating and events by locals

10. Fostering and

enabling existing and new self-help and mutual-help groups and networking; and

11. Recognising and

supporting intergenerational respect, care and nurturing.

THE FRAMING OF SEA-EPSN REPORTS

The following sets

out the framing of SEA-EPSN Reports. This framing follows closely the protocols

agreed to at the Tagaytay Pre-test Gathering. Some team members had little or no appreciating of, or agreement with

much of this framing.

o

Nothing

happens unless locals want it to happen

o

Locals are the authority on their own wellness

o

Locals typically know what is missing from their wellbeing

o

Local carers and nurturers are typically present and informally

networking among the traumatised; they typically extend care and nurturing in

everyday contexts - we seek, identify, respect, care, nurture, and enable them

o SEA-EPSN field

team members take no action that harms or even potentially harms anyone. If

there is any chance of harm resulting from information we gather, then the

relevant people’s details are not passed on.

o

SEA-EPSN member field action supports the local people’s

resilience, competencies, resources, wellbeing, mutual cooperating and human

rights

o

Our action enables and supports locals to carry out their own healing caring using their own local healing caring ways –

fostering self-help and mutual-help caring and networking among

the local carers

o

We may offer to share other healing ways, if they want them – allowing them to tap into and adapt for

example, Australasian, Cambodian, Indonesian, Pinoy, Thai, Timor Leste, and

Vietnamese wellbeing experience

o

Prescribing outside

healing ways may alienate and harm – early action takes the time to

respectfully and sensitively sense the local context – wisdom is needed

o

SE Asia Oceania everyday life-ways and worldviews are reflected in

their psychologies and social psychologies and vice versa – a central theme is

personal, familial, and community inter-connectedness, inter-relatedness and

inter-dependence. Support action is resonant with, and supports this way.

o

This interconnectedness extends to notions of wellness and being

well (wellbeing) and recognises, respects and supports the potency of the

interconnectedness of these ways:

o

Emotional wellbeing

o

Cultural wellbeing

o

Psycho-social - interpersonal, family, friendship, and communal

wellbeing

o

Economic and livelihood wellbeing

o

Mindbody wellbeing

o

Habitat, geo-social, local place and environmental wellbeing

o

Spiritual and transcendent wellbeing

o

Shared everyday-life wellbeing

o

Creative and artistic wellbeing

It is recognised

that returning to normal local everyday life typically has substantial

wellbeing related psychosocial effects and SEA-EPSN actions aims to sense these

local life ways and their effects, and support normalising of local everyday

life ways.

It is further

recognized that:

1. The many

traumatizing contexts in an emergency may all have a profound impact on psychosocial wellbeing

2. Emergencies typically

have visible and invisible effects

3. Large numbers of

traumatized people invariably stretch service delivery processes beyond

capacity. Typically, not enough professionally trained trauma support people

may be mobilized.

4. We recognise that

the very ways local people may use to live with the aversive affects of

emergency contexts – blocking emotions and feelings, disconnecting from the

world, distancing others, becoming rigid in mind and body, harbouring hatred

and revenge and the like have survival value; they are also problematic in the

longer term.

5. Local people’s

ways of adapting to and living with trauma and other aversive affects of

emergency contexts may make these effects invisible and very difficult to

identify.

6. SEA-EPSN processes

support tapping into and strengthening the self-help and mutual-help networks

among the locals. These support processes may limit the impact of emergency

events and speed up the return to everyday normal functioning and wellbeing.

7. SEA-EPSN

recognises that local

self-help and mutual-help processes, practices, nodes and networks are critical

components of local self-organizing process through which local resilience and

wellbeing may be re-established and/or maintained.

8. It is recognised

that adequate nutrition, good sanitation and clean water, stopping the spread

of infectious diseases, adequate shelter, safety and the like are all crucial

in the early phases of support. Establishing basic safe and sanitary conditions may maintain survival at

base-line value.

9. In promoting and advancing life, people may hold a

space for wellbeing - creating contexts for self-organizing life-ways to

reconstitute living wellness. For this, psychosocial and wider

wellbeing support may be crucial.

10. SEA-EPSN

recognises that the end of a conflict may increase distress for a certain time,

due to the following:

a) People hearing

news of deaths and physical and psychosocial injury of family members,

relatives, or friends

b) Families may find

out that their home and/or other property has been destroyed, lost, looted, or

taken over by others

c) Tensions in the

community may be exacerbated by the return of demobilized combatants (adults

and children) who still have weapons.

11) During emergencies

and emergency contexts the situation may change very rapidly. SEA-EPSN

recognises that data collection and its analysis must be done quickly and as

thorough as possible given presenting circumstances. The results are ideally

distributed quickly to decision-makers. SEA-EPSN team members endeavour to collect

as appropriate to context. The analysis is as specific as possible to ensure

the best development of community-based, phase-specific action. We recognise

that in many senses the Situation Report can never be ‘complete’.

THE

SITUATIONAL REPORT

INFORMATION ABOUT THE CONTEXT OF THE DISASTER

1. SPECIFY THE LOCALITY

The area visited

is the municipality of Pikit in the Province of Cotabato on the Island of

Mindanao, in Southern Philippines. Pikit has seven Barangays (districts). We

stayed and worked in Takepan Barangay made up of a number of Situ - small

hamlets – from a few to around fifty houses typically made of local materials.

The word ‘Situation’ as in ‘Situation Report’ derives from the Latin ‘situ’. We

also had a visit to Pikit and a small group had a return visit to Pikit to meet

the Social Work area of the Pikit Local Government. The local Military Barracks

was also visited.

2. DESCRIBE THE NATURE OF THE EMERGENCY

The local

population has experienced repeated outbreaks of war since 1997, the latest in

February 2014 with over 35,000 internally displaced people. There have been

many wars over the past 250 plus years. The central triggering theme is

‘Islamic people seeking self-determination’. From the Islamic Moro people being

the massive majority in the past, they are now less than 20% of population

among the Christian majority. The Islamic people score low on most

socio-economic indicators. There are a few Lumad indigenous people in the Pikit

region. Conflict results in civilians of all three groups in the Pikit region

fleeing into the evacuation centres such as primary and secondary school

playgrounds, wayside stopping places along the main road and in church grounds.

The main protagonists are the MILF (Moro Islamic Liberation Force) and the

Philippine Army.

Many Situs in

Pikit have both Muslim and Christian families living together in close

harmonious cooperative rice growing and farming communities. Typically, the

Situ leader role is rotated between Muslim and Christian, with a deputy leader

selected from the other religion. Conflict places pressure on the harmony of

these mixed Situs. Muslim and Christians cooperatively share most of the

evacuation centres, e.g. the large Catholic Church in Pikit.

During conflict,

each situ is typically completely evacuated, with the civilian population in

affected areas (ranging from 20,000 to 40,000) compressed into evacuation

centres for the duration of the conflict. During a recent conflict 160,000

people were displaced in Pikit and surrounding areas.

The main (sealed)

highway between Cotabato and Davao is a key military feature, with both sides

fighting for control of sections of the road, especially key bridges. The road

is also a key conduit for local farming communities fleeing to evacuation

centres. Civilians may and do get caught in the cross fire. The local

population are farmers (mainly rice) and use water buffalo to plough. After

cessation of hostilities and when the men sense it is safe, they return to

check on livestock and work their fields, returning at night to the evacuation

centres. People get killed on these Situ return trips. During hostilities

livestock are lost or killed and houses are damaged or destroyed. Protracted

conflict is placing immense strain on the local farming communities.

Locals are also

exposed to flash flooding on the irrigation area west of Pikit and El Nino

drought on the east side where watering uses spring based water. The last El Nino affected more than 900,000 families

(including Indigenous peoples called Lumad) throughout Mindanao.

Inter-family

feuding called ‘Redo’ is an ongoing danger with killing and payback killing

going on for years. Redo has potential to trigger wider conflict and all-out

war. It is not unknown for a family member who is also a member of the MILF to

be killed. Local families have been known to attempt to rake in MILF and the

Philippines military into their redo dispute.

We held a meeting

with the military at the Army Headquarters south of Pikit. They made it clear

that peace and peacekeeping are their priority and that they are very careful

not to be drawn into redo contexts.

Some have noted

that conflict tends to have a three year cycle with conflict erupting in the

year prior to elections. This observation may be usefully explored and factored

into peace talks if there is any substance – by what process?

ENTRY PROCESS

There

are three local NGOs in Pikit - each with their head offices in

There

is also a community-based voluntary social support network (CBO - civilian

based organisation) coordinated through the Catholic Church in Pikit. This can

be linked with via any one of the local NGOs. It has ongoing action supporting

each other in the network, experiential learning gatherings and outreach

supporting local communities.

We had

discussions with the Pikit Municipal Government Social Work Section which has a

three person team to support 9000 families (over 40,000 people). Their

resources are typically stretched beyond capacity, even in peace times. In times of conflict they may play a key

coordinating role between local support bodies and between local and

international bodies.

It is recommended

that at

all times visiting Aid Organisations arrange to be accompanied by local

people from the above organisations (or others arranged by these local people).

There is still potential for harm from kidnappers and hostile elements, especially

for people from America or people that may be mistaken for Americans. The

specified locals can act as interpreters and provide a constant guide to

cultural protocols. In this rural environment, outsiders stand out (especially

if over five foot ten inches tall), attract attention, and may be perceived by

locals to have energies that unsettle, regardless of intention.

Prior to arrival,

arrange for local accommodation and briefings through the Manila offices of the

three NGOs who typically, have the latest information on events unfolding in

Pikit Municipality - including security.

For international

aid organisation contemplating setting up a base in the field they would have

to negotiate entry with the national government, local military, and the local

government as well as link with the local NGOs. The local farming communities

each have a well evolved night security patrol and are well armed. There is a

nightly password process and call and respond process that has to be complied

with or gun fire will ensue. As well, night movement on the ground has the

added hazard of aggressive cobras snakes.

3. DETAIL THE LOCAL COMMUNITY SUPPORT

STRUCTURE

There

are three Local NGO’s in Pikit - each one has their head office in Manila (see above

and refer SEA-EPSN Secretariat for introductions.

Our

team received a briefing from one of the Pikit NGOs in Manila and we were

supported locally by members of that NGO who met us at Cotabato airport with a

van that held our team and provisions. There is a massive military presence the

moment one leaves the airport, with no-man’s land of around 40 metres to cross

on foot. Either side of this is flanked by tanks and soldiers with guns at the

ready, with machine gun manned towers on either side. Be aware that Cotabato

Airport has planes land going uphill and there is a brief take off as the plane

goes over a crest till it bumps down over the crest with the balance of the

landing strip going downhill. To the right of the plane on taxiing to the

terminal are helicopter hangers with military helicopters at the ready.

Some members from

Pikit NGOs head offices attended

the SEA-EPSN consultative workshop in Tagaytay, August 2004.

There

is also a very active community volunteer network (around 50 people) through

the Catholic Church centre in Pikit who tend to provide services, with some

support for local mutual-help. While being natural nurturers, their primary

focus is practical (e.g. food distribution). They tend to give spontaneous

psychosocial support on-the-run as they do their practical work. They may not

fully sense the psychosocial benefits of their practical actions. We sensed

they saw ‘psychosocial’ as ‘a specialist area of main focus by trained experts’

delivering psycho-social services. Our sense is that these volunteers are doing

superb psychosocial support work without necessarily knowing it, and this

works.

There

is a Takepan Barangay evacuation plan in place. This has been evolved at the

‘top’ at the Council level. This could be explored further, especially as to

acceptance, familiarity and preparedness to use this plan at the grassroots.

Some

(maybe all) Situs have an evacuation plan and process in place.

Also

some, (perhaps all) families have an evacuation process.

These

plans/processes are very practical – including auditory and visual based

signals to evacuate, who to bring what, how to ensure no one left behind,

evacuation route and back up routes to avoid hostilities, even visual signals

between MILF and local citizens (for example, ‘we are passing through and mean

no harm so let us pass’). Some local civilians have the latest military weapons

and ammunition.

There

is a well armed local civilian militia that patrols at night to ensure

security. Two went silently without being seen or heard within feet of us when

we were sitting outside on a dark night except seen spotted by one field trip

member with superb night vision. These local civilian militia on patrol typically travel in pairs without

lights in the night. A Takepan Barangay law requires people walking at night to

carry fire (a torch is not allowed) and to identify themselves when asked by

security.

It is totally inadvisable for

NGO people from outside the area to be outside after dark in the Pikit

municipality.

It would be extremely wise to

learn the expression ‘Identify yourself’ and be able to convey quickly and

clearly who you are if caught out at night without flame! Also find out the

password for each night. Better still, stay indoors after dark. Find out the

local protocol for using the toilet after dark, some of them may be some metres

away from dwellings. Some nights can be black. UN-INMA member was not briefed

about behaviour at night nor briefed by the host family till the third night.

He had stayed indoors, though advanced notice was really vital.

A 5pm

(twilight) curfew is sensible for members of visiting international NGOs.

Always

meet way away from the road and under cover of darkness at night.

4. DESCRIBE THE VARIOUS CONTEXTS.

Currently there

are no hostilities.

The various Situs

are one context. Families and most of the community of a Situ are available to

congregate outside farm work hours by prior arrangement through the local

NGO’s. Imams (Muslim religious leaders) may also be present and be prepared to

talk. People speak English or local translators are generally available,

including local NGO people. Each community readily speaks and tells stories of

the practical ways they use to support themselves before, during, and after

conflict. Local ways of mutual support

are well established and used. Prayer, storytelling and mutual caring

presence (e.g. mothers holding children with both mother and children crying).

One Imam after composing himself told us that at times during the last conflict

he himself was so terrified and emotionally devastated that he was of little

religious or other support to others. He would wake crying and go to sleep

crying. It was that hard; though he did what he could.

By arrangement

through the local NGOs, and with Situ people knowing the purpose of the

meeting, it may be possible to have meetings with the leaders of a number of

Situs at a Barangay meeting place. Muslim Imams may be available to join these

meetings

By arrangement

through the local NGO’s it may be possible to meet the principals of the local

elementary and high schools that are distributed through the Pikit Region. We

were able to engage in structured experiences and free-form (spontaneous play)

within a cultural healing action psycho-social framework with the whole elementary

school child population together (600 children) at Takepan Elementary School

(as well as later at the back of the school, with the children grouped into

three groups of around 200). We also engaged with some classes at the Takepan

high school using focused group discussion and storytelling and spontaneous

music, song and dance using peace as a theme drawing upon cultural healing action

processes evolved by PETA – Philippines Educational Theatre Association led by

a PETA graduate on our Team.

During Conflict

During conflict,

the three NGO’s may be able to negotiate safe passage down the highway to Pikit

from either of Cotabato or Davao depending upon the moment to moment context.

The Manila head offices of the three NGOs may assist in rendezvousing with the

visiting team at Cotabato Airport or Davao Airport. There is no airport at

Pikit. The three NGOs may direct you to the various evacuation centres. Tee

this up before flying to Mindanao.

5. BRIEFLY SPECIFY THE GEOGRAPHY AND

ENVIRONMENT OF THE AFFECTED AREA – NATURE OF THE TERRAIN AND VEGETATION.

The land is

essentially a flat river valley with some higher rises. The main road is sealed.

Side roads are unmade with muddy spots. There are a system of narrow walking

paths through the rice fields. Most high points have armed military lookouts.

Military vehicles filled with armed soldiers patrol the road with rifles at the

ready and there are frequent military checkpoints. In passing one of these

trucks you experience having a row of loaded guns pointing at you.

Watch for cobras

in grassy areas. Many of the Situs are along the main road with some back a few

kilometres. There would be sticky mud in the wetter seasons. They typically

have two rice crops.

6. WHAT WAS LIFE LIKE BEFORE THE DISASTER?

There is

cooperative peaceful living in farm-based Situs with typically harmonious

relations between Muslims and Christian families.

Ongoing redo has

been a continuing concern.

7. WHAT CHANGES HAVE OCCURRED DUE TO THE

DISASTER? WITH WHAT EFFECTS ON INDIVIDUAL AND COLLECTIVE WELLNESS?

The situation we

have in Pikit is a protracted war context interspersed with months of peace.

The presence of military patrols is the only real visible signs of the

emergency. We gather from locals that the effects of the conflicts are

typically invisible. While all 40,000 in the area have been effected, we sense

that perhaps up to one in five (8,000 people) are seriously affected

psychosocially. This is what locals refer to as the invisible aspect of the

conflict. Disturbingly, some children are harbouring deeply entrenched hatred

driving a revenge to be potentially catastrophically released in another

fifteen to twenty years – thus perpetuating the cycle of violence. One young

child was found to have a very large collection of high calibre bullets hidden

in the long grass near his home. He told his mother they were there for him to

use when he grew up.

Planting bamboo as

a symbol of delayed revenge is common – where every notch on the bamboo is

another enemy to be killed. To reframe

the meaning of bamboo, one of the

NGOs has a peace-building

process titled ‘Bamboo for Peace’. One NGOs ‘Integrated Return and Rehabilitation Program’

entails Building Sanctuaries for Peace.

Another program is the linguistic skills program that is assisting youth who

have had their education devastated by protracted war.

If

the team had received prior briefing on these

programs in the Pikit region we could have linked with the local people

involved and gained feedback and provided support. Not knowing of them meant a

missed opportunity to engage and support.

While some

traumatised people may be known to family, teachers, religious leaders and the

like, I sense that many may not be recognised. 8,000 would stretch local NGO

and other local capacity beyond effectiveness.

A local way of

coping with trauma is to not showing emotion. Many people do not want to talk

and plan for evacuation, as it is seen as pre-emptive and assuming as a fait

accompli what they never want to occur again.

One of the key

roles of the local NGOs in time of conflict is the daily delivery of food and

water to the evacuation centres under the protection of a white flag ceasefire.

They have very effective processes for carrying out this essential service with

cooperation of both sides in the Conflict. This seems to be well established

and it works well.

We sense

Identifying local natural nurturers and their spontaneous friendship networks

and supporting them is a way to reach out in support of the traumatised. We

assume that the

Manilla head office people of the other two Pikit NGOs where well briefed about

our role in Pikit, namely, finding the local natural nurturers and supporting

the evolving of mutual-help networks in the Pikit Region.

UN-INMA

wrongly assumed that the local members of the NGOs were also similarly briefed. They were not briefed; only after returning

to Manilla was it found that the local NGO people we were working closely with,

felt extremely threatened by our (especially UN-INMA) reaching out to local

natural nurturers and evolving local mutual-help networks. Local NGO people

perceived this as potentially doing them out of a job.

The

local NGO people we were working with failed to see scope for multiple lateral

integration between lateral/bottom-up and top-down processes, or appreciate the

scope for shifting from vertical integration to lateral integration.

To protect themselves, they

sought to undermine the UN-INMA contribution. This

is a fundamental issue that needs to be worked through. Refer Interfacing

Complementary Ways and Government and Facilitating Grassroots Action.

8. WHAT ISSUES CONTRIBUTE TO DIVISIVENESS IN

THE DISASTER REGION? IN THE WIDER REGION?

Important feedback

from local experience is that international NGOs who act unilaterally without

detailed knowing of the local subtleties, and without acting cooperatively,

complementarily, and convergently with the local and other international NGOs, have caused strife in the past. This

strife had the potential to escalate hostilities within the civilian population

and the armed forces. This issue was mentioned by a number of influential

members of the Pikit community. This issue may never occur if the following

core principles are always followed, namely:

1. Liaise, converge and

cooperate with and complement the actions of local NGOs and CBOs

2. Never act

unilaterally and never ‘protect you own turf’

As stated, most

rice growing Situs have Muslims and Christians living in close harmony. People

run to their nearest evacuation centre. It follows, that evacuation centres

have Muslims, Lumad and Christian people all mixed together. There are a number

of different Christian denominations present.

Any outside body

coming to provide aid:

1. Must support all present without discrimination

2. Must refrain from any attempts to convert

Both of these have

happened. It caused massive strife, and the outside body was immediately

escorted off Mindanao and banned from any further role in Mindanao.

Redo is an ongoing

concern with local peacehealing processes in place to stop this as a cultural

phenomenon.

The quest for self

determination, while a long term (200 plus years) determined aim by many, leads

to hostilities playing havoc with the civilian population.

Mindanao:

o

Has a major percentage of Philippines

natural resources

o

Is the major source of food, and

o

Is perceived as an integral part of

Philippines.

There is some

mistrust between Christian and Muslim through conflict-based happenings, though

everywhere we went, both Christians and Muslims reiterated the theme of

inter-religious harmony. In many contexts the team visited, this harmony was

self-evident. A case in point was experiencing the outdoor preparation for a

shared communal evening meal in a rice-growing Situ – the setting was idyllic

in the extreme.

9. WHAT, IF ANY, ARE THE ANTICIPATED

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE DISASTER AREA?

There is a

pervading concern that redo could retrigger conflict.

The peace process

talks are proceeding with international observers – many from Muslim countries.

A process is in

place in the Pikit and wider regions to investigate breaches of the peace

process and impose penalties for a breach.

Kidnapping for

cash by ‘criminal’ elements continues (e.g., the pentagon gang).

10. HAS ANY POPULATION MOVEMENTS HAPPENED AS A

RESULT OF THE DISASTER? ARE ANY EXPECTED TO HAPPEN? WHAT EFFECTS ARE THESE, OR

FUTURE MOVEMENTS HAVING ON WELLBEING?

Yes 40,000

evacuees (internally displaced people) during a recent conflict with 160,000 evacuees

in the surround areas. Most of these people return home after hostilities

cease. Some people have elected to stay with family and friends away from their

home area. Some families have not returned to their mixed communities, choosing

instead to move to a ‘same religion’ community. The presence and maintenance of

‘mixed religion’ Situs with harmonious relations contributes to the peace

process. This move to same religion communities is seen as a retrograde step by

many.

11. WHAT HUMAN RIGHTS HAVE BEEN, AND ARE BEING

VIOLATED?

The right to quiet

habitation together in their place is being violated. Some instances of rape

are reported.

12. WHAT IS THE SECURITY SITUATION? WHAT KINDS

OF, AND WHAT DEGREE OF VIOLENCE IS OCCURRING, IF ANY?

1. Regular military

checkpoints; take care not to have small groups of females travelling alone as

there was an incident of undisciplined conduct at a military checkpoint

threatening rape or worse to a female external NGO member a few weeks before field

trip.

2. Community security

patrols.

3. International

monitoring of peace process

4. Occasional

redo-based killing

5. Some stock

stealing in outlying areas

Specifying

the Affected Populations

Refer local NGOs

on the following Questions

1) Provide estimates

of population by age, gender, and vulnerability within each of the following:

a) Refugees, IDP,

existence of old refugee groups/displaced populations (if this is a protracted

disaster) returnees, non-displaced disaster-affected populations, others.

(1) Single mothers

Not known

(2) Raped

Not known

(3) Pregnant through

rape

Not known

(4) Survivors of torture

No reported

incidence

(5) Survivors of

sexual violence

Not known

(6) Orphans,

unaccompanied minors, and homeless unaccompanied children

Not known

(7) Children /

adolescent heads of household

Not known

(8) Demobilized and

escaping child soldiers, ex-soldiers, active soldiers, ex-"freedom

fighters"

Some reported use

of child soldiers by MILF – no knowledge of the whereabouts of these child soldiers;

incidents where bombs set by child soldiers have killed Philippines military

(9)

Widows

Not known

(10) Physically

disabled and developmentally delayed, Elderly, Chronically mentally ill: with

families in institutions, or in other places, Others

Not known

Further specifying

of the above may usefully be carried out.

2) Provide an

approximate map of the locations and estimated numbers of various types of the

affected populations?

(Map)

3) What is the

location and number of those living with relatives, and local people in rural

and urban areas?

Not known -

further specifying of the above may usefully be carried out.

4) What is the

average family size?

Typically 5 to 7

5) What is the ethnic

composition of the affected population(s)?

Christian and Muslin

majority - a few Lumad families; UN-INMA was briefed by very well educated two

Lumad people from a University in the Region.

6) What are their

places of origin?

Some of the older

Christian farming people moved to the area 50-60 years ago from Northern

Philippines, and joined Muslim farming communities. Others have always lived in

the local region

7) What are the

locations of the affected populations:

a) in the

countryside, transit centres, camps, besieged villages, towns

Currently living

in their Situs - local NGO’s would provide a map and details regarding

locations of evacuation centres and besieged civilians, houses and Situs in an

emergency context.

8) Provide a picture

of special needs groups needing support, for example:

a) Orphans and unaccompanied

children

b) People who are

incapable of self-care

c) Women who have

been raped

d) Escaped/demobilized

child soldiers

Not known -

further specifying of the above may be usefully carried out.

9) Identify and rank

the causes of mortality and morbidity among the affected local populations.

Not known -

further specifying of the above may usefully be carried out.

10) Identify the

traumatic nature of the affected local population’s experience.

With 6,000 people

squeezed into a school playground, typically, people have less than a square

metre of space. One has to stay on this space 24 hours a day for perhaps 7

months. One has to stay low in crawling to the school perimeter to use pit

toilets. The rice farmer men typically take their hoes to the evacuation centre

and use these to make a system of drains so the ground does not get muddy when

it rains. They also use the sharp edge to cut saplings and make what look like

beach umbrellas to shade their families from the very hot sun. This physical

work helps discharge an awful emotional combination of extreme anger at the

outbreak of fighting combined with a complete helplessness to do anything about

it. (This was shared during a discussion with a Muslim men’s group (16 men) in

a rice growing situ.) Armed conflict including mortar fire, high powered

automatic weapons, helicopter and plane-based weaponry was being used sometimes

only 750 metres away from evacuation centres and occasionally closer. The noise

and ground vibration was reported as being terrifying. One elderly Imam said

with great emotion that he woke up crying every morning and he went to sleep

crying. All around him women and children were crying. Many times during the

stay in the evacuation centres all the bodies would leave the ground when heavy

munitions would hit too close. One observer said that he saw children very

quickly adapting to this abnormality as the new ‘normal’. He saw children

terrified by helicopters spewing flaming rounds of fire – then a few days later

the same children would wave to them. While adaptive, this is at the same time

a pathological context for the children to be caught up in.

Takepan Primary

School used as evacuation centre

Above is a photo

of the Takepan Primary School. It is the set of buildings below the road. We

engaged with the whole school population in the area between the central building

and the road. We then divided into three groups and moved to the playground at

the rear of the school. On our first two nights in the Region we held a meeting

under lights on the front porch of the building opposite the school in the

largest building beside a car park. The military strongly advised us never to

do this again as we would be targets for harassment or worse. On the next night

we met outside one of the homes in the dark at the rear of the school amongst

the trees.

Photo of

surrounding rice growing Situs

The above photo

shows the rice growing areas and other small farms and the Takepan Primary

School evacuation centre (where the three coloured lines come together). The

people from the farming areas to the right of the photo flee to the Takepan

High School down the road towards Pikit a few 100 metres. The local people of

the area young and old are experienced in finding the best way to the

evacuation centre in the moment-to-moment changing context when war breaks out.

11) Is there any data

already being collected, and distributed, including up-to-date information on

the security situation, human rights violations, and other problems having, or

likely to have, an impact on wellness?

Yes. Refer

Secretariat and the NGOs – research has been done that was not available to our

team including research identifying at-risk populations.

1) What were the

wellness levels like before the disaster?

Because of the recurring

conflict, similar to now

2) What past and

ongoing exposure is there to traumatic events and violence?

Repeated conflict, with some adaptive

behaviours having problematic consequences

3) How sudden was any

move, if any?

Generally, the

farming communities around Pikit have short notice of impending hostilities

with most making it in time to the evacuation centres. Some get caught in the

cross-fire.

4) When and how did

displaced people and refugees arrive in their present locations?

Most have returned

to their farms and homes in their Situs after the last conflict ended early in

2014. Some are still with families in Cotabato and other places.

5) What have they

gone through?

a) Killings,

executions, having missing family and friends?

·

Extreme hardships in the evacuation

centres may include food shortages

·

Lack of potable water, especially for

washing following toilet use (both a fundamental and religious aspect of their

way of life norms)

·

Illness, including dysentery and diarrhoea

·

Initial lack of shelter – 16 men from one

Situ took up to 5 months to erect 53 ‘bunkers’ (single pole with woven reeds on

top similar to a beach umbrella) to shelter each of their families (with

psychosocial payoff in terms of feeling good about providing for families

·

Loss of farm animals, loss of crop and

crop seed

·

Destruction/damage to homes

6) What of any of the

following has taken place? Is taking place?

a) Domestic violence,

including child abuse

b) Sexual violence

against adults and/or children

c) Breakdown of traditional

family roles and support networks

d) People’s loss of

their future with family and friends following deaths of close ones.

e) Harassment and

violence against whole or sub-groups of populations, e.g., against children,

women, or other groups?

f) Epidemics with and

without deaths

g) Abduction

Re (a) to (g)

Check with local NGOs – heard nothing about any of these

h) Disruption of status (e.g.,

economic decline, loss of power in the community)

Disruption of

farming cycles causing economic hardship. Some desire to evolve a local farming

cooperative. Some reports of destructive consequences of combining political

roles and being members of cooperative boards of management. Some suggested

including rules in the setting up and incorporating of farming cooperatives to

the effect that any board member must not run for political office for say at

least four years following ceasing being a member of a cooperative board, and

any person holding political office must not run for a position on a

cooperative board for four years. Any person violating these rules to be

automatically removed from office and ineligible to hold office for eight

years.

i) Torture

Check with local

NGOs – heard nothing

j) Bombing, armed

attacks, artillery shelling, mining, etc

All indirectly

effected (nearby hostilities); some locals (how many) caught in the cross fire

k) Deprivation of

food/water

Check with local

NGOs – heard reports of food shortages and some reports of Philippine army

blocking necessary food supplies from getting to the evacuation centres – fear

of food being accessed by enemy – this needs cross-checking with others

(Layson, 2003, In War, the Real Enemy is War Itself). We understand that using

deprivation of food as a military strategy is banned by international

agreements. There were water shortages in some centres.

l) Separation from

family

Instances of

separation from family creating massive anxiety in children with some children

in post-conflict settings refusing to go to school and wanting to stay with

their mother for fear they will never see them again

m) People being

forced to commit violence against members of their own family, community, or

other people

Check with local

NGOs – heard no report of this

n) Disruption to

important cultural and social rituals; to family and community structures

Disruption of the

normal cycle of farming and community life. Inability (for some) to attend

normal places of worship while in evacuation centres

o) Imprisonment,

detention in re-education/ concentration camps and other kinds of settings

Check with local

NGOs – heard no report of this

p) Ethnic, political,

and religious disputes

Check with local

NGOs – sense there was some unrest in evacuation centres from exacerbating

factors – typically, quickly mediated by existing community frameworks – who

were the peacemakers?

q) Lack of privacy

Reported as a

continuing issue (especially for women) given cramped out-door quarters in

evacuation centres

r) Extortion

Ongoing kidnap for

ransom - though less around Pikit at the moment

Actions Addressing Wellness Needs

1) How do people

understand and respond to violence and suffering?

Women tend to

speak of care, comforting and nurturing, prayer, and storytelling. Men tend to speak

of practical action in caring for family – returning to check farm and

livestock, working the farm on day-visits from evacuation centres when safe to

do so; building bunkers (shelters) for their families; also digging a system of

drains in the evacuation centres with their rice work hoes (10 inch square

metal head with sharp blade on one side and rake type prongs along the opposite

side). As rice farmers they are naturally good at simple water flow

engineering. Geo-emotional enabling spaces.

This suggest that

psychosocial support may be take account of these gender differences – using

storytelling, and nurturing themes with women and practical work as wellness

healing with the men – e.g., feeling calmer, energised and more relaxed after

digging a ditch.

UN-INMA introduced

the theme of whether they use physical activity to calm down when they get

angry annoyed etc in peace time. The locals recognised that they were helped to

feel better by hard physical work in the evacuation centre, though they had not

used this process in peace time. They said that they would use this process in

the future.

2) Give a feel for

how communities, families, friendship networks and people among the various

peoples affected respond to the consequences of the disaster.

We were left with

a strong sense that the various sections

of the local communities are very experienced in self and mutual care. They

evidenced considerable psychosocial resources and resilience. It is recommend that international aid

bodies support and complement these local ways and do nothing that undermines

or replaces them.

3) What are the local

ways people use to support themselves and each other?

They endeavour to

stay in the family unit and with other families from the same situ at the

evacuation centre. Everyone knows that it is virtually impossible to safely

move between evacuation centres, so every endeavour is made for families and

communities to get to the same evacuation

centre. Young and old have experience in recognising when hostilities break out.

Everyone knows what to do; for example, the steps to take to maximise the

chance that livestock will still be there when hostilities cease – especially

expensive important animals like water buffalo. Whether to make for the

evacuation centre or move away from the centre to assist the elderly and sick

in their Situ to get to the evacuation centre. They know how to read the sounds

of hostilities, and from this, choose the best way to the centre. They all know

the networks of pathways through the flooded rice fields – typically linked

rectangular grids. Men engage in mutual-help in constructing family shelters at

the evacuation centre. These community-based social actions support and sustain

community cohesion and support. Drainage is a theme conducive to coherence in

the men. Women staying close together with children in close proximity – thus

creating the context of being very close together sharing unfolding experience

with familiars – children surrounded by familiar faces – normal Situ social

exchange concentrated – therapeutic community - may be likened, in some senses,

to marathon encounter groups of the Seventies in Big Sur California – embodying

understandings of how to live in close community life as crowd and audience to

each others’ pain and grief –– people sharing experience of reconstituting

their reality in this confined space – with what experiential learning? (Refer

Chapter Eight in Fraser House Big

Group).There is potential for bonding to emerge from these

intense shared encounters. The experience from another context is germane –

people from fire affected areas in Victoria, Australia suffering the death and

injury of family and friends and massive loss of property and way of life,

speak of by far the best psychosocial-emotional support they receive coming

from fellow fire-affected people.

4) Do the people

affected ask for help or for psychological support from the other locals when they

need it? If yes, how are these requests for help seen by their community? How do the locals respond to these requests?

Check with local

NGOs – Within the comments in 3 above, heard no report of this – rather sense

that people tend to not talk about it if they feel awful.

5) Who have you

identified who are:

a) natural nurturers

and carers

A list of these

with contact details was attached with this report to the Secretariat (not

included in this copy).

Given a potential

at-high risk population of around 8,000 (the exact numbers are at this stage

hard to determine), providing psychosocial support to this many people would

stretch available resources beyond capacity. Having the local NGOs supported in

tapping into and enriching these local natural nurturer networks may be the

only way to support 8000 at risk people. Refer E DeCastro)

After leaving

Pikit found out that Ernie Cloma from PETA identified natural nurturers among

the teaching staff of both high and elementary schools in the Pikit region when

he was engaged by one of the local NGO to run theatre arts workshops (with a

peacehealing and psychosocial support focus for teachers and youth some months

ago.) Perhaps these teachers may be identified and approached to give feedback

on:

·

Their experience of using theatre arts

·

The adaptations they have made

·

The outcomes they have been getting

·

Any youths with psychosocial dysfunction

they have identified

·

If they have not used theatre arts, what

factors would have contributed to this?

·

What additional experience in the

processes would they welcome, if any?

Ernie worked in

the two schools in Takepan where our team also engaged in similar theatre arts.

Regrettably, the NGO supporting our team (while they knew of Ernie’s work teed

up by another NGO) did not inform us of

this work by Ernie. This meant we missed an opportunity to follow up

Ernie’s work with the local teachers. We also missed a golden opportunity when

we did not arrange to have the teachers witness and potentially learning from

our engaging with the children in cultural healing artistry. That was a major failure.

One of the local NGOs (refer Secretariat) have trained many youth

volunteers in Mindanao:

158

youth volunteers with 142 completing the course – of these 72 eventual stayed

on to regularly conduct play therapy sessions among children in their

neighbourhood

18

day-care centres

29

elementary school teachers from six schools

They

can advise how many of these were in the Pikit region. Note that this

information was not conveyed in our Manilla briefing. If it was, we could have

followed this up in the Pikit municipality. Yet another lost opportunity!

These volunteers regularly conducted play therapy sessions among

children in their neighbourhood. Ernie Cloma was used for creating action

resources for this project. Had we been briefed before being sent we could

have perhaps identified these volunteers in the local region and obtained

feedback and worked with them in capacity building. Another major failure!

One

of our team was mentored by Ernie and trained at PETA. Presumably he knew of

Ernie’s involvement in the Pikit region and never mentioned this before or

during the trip. This PETA person, while experienced in cultural healing

action, was not at the Tagaytay Pre-test and not familiar with the SEA-EPSN

resources, guidelines and Proforma, was not familiar with self-help and mutual

help processes and unfamiliar with Rapid Assessment. Another missed

opportunity!

b) Nodal (key

linkers) people in these networks

The priest in the

main Catholic Church in Pikit is a key nodal networker

6) How can these be

contacted?

Refer Pikit priest

and local NGOs.

7) Are there any

support or self-help groups within the refugee community and or host support groups?

(For example, among women, children, adolescents, adults, elderly, among the

disabled, or between women and men).

Each Situ tended to be its own mutual-help group. The priest of

the Pikit Catholic Church and the Imams and some others were nodal networkers. The three social workers with the Pikit local

government also link informal self-help groups though we did not have

opportunity to link with these.

8) What resources,

coping skills and behaviour strengthening is unfolding at personal and

community levels relating to restoring wellness?

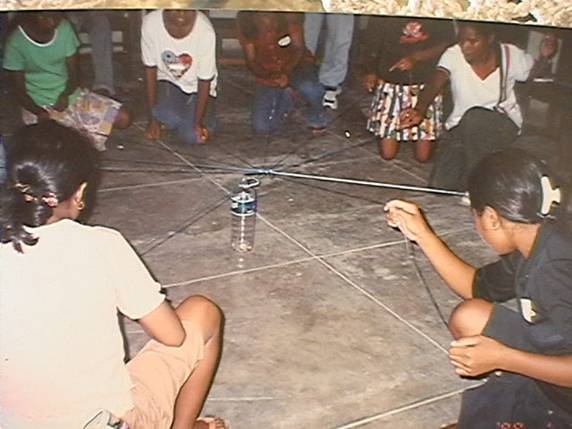

The priest of the Pikit Catholic Church’s

volunteer group has regular reunions for strengthening their network using

structured experiences and hypothetical enactments; for example, a group

challenge involving cooperation for success shown below.

With all holding

strings attached to pencil everyone has to cooperate closely to place the

pencil in the bottle

Team members passed

on healing ways to around eleven of that priest’s group (including the priest),

including cultural healing artistry processes (by PETA member of the Team).

Healing ways were explored with a men’s group at a Situ where Muslim people

were in the majority. A woman’s discussion and storytelling group was also

conducted in the same Situ.

9) What security

concerns are there, if any, about releasing these people’s names and contact

details?

There appears to

be no current security concerns about releasing names.

10) Specify the

healing ways if any, that are used by the people affected:

a) Samples:

Widely used and

useful

ii) Body approaches

Tend to be used:

o

For example, by men digging ditches and

erecting bunkers.

o

By women attending to food preparation,

washing and other daily chores, and children playing chasey, thong based games

and the like – it seems that there is little consciousness that these everyday

bodily activities may have a normalising effect on psychosocial wellbeing and

making this known may not add very much.

iii) Group and

community approaches

In Pikit, as is

common throughout the Philippines, whenever psycho-emotional strife occurs, the

place to start healing in this culture is with the whole community. Once community healing is well under

way then smaller group healing occurs within families and friends. Then

individual and interpersonal healing occurs. We have already noted the use of

group and community approaches based on families and Situs acting in concert.

Any outside international Aid organisation

coming in with expert service delivery people trained and experienced only in ‘individual treatment’, will inevitably engaged in cultural imposition

and actions that have the seeds to undermine and collapse local way. This

occurred in the Mt Pinatubo eruption where local people were well underway with

effective whole-of-community healing when psychologists from America and

Denmark wanted to treat people one by one. The locals refused to engage with

the visitors. Typically claiming to offer psycho-social support, international aid professionals often have little or no experience in the social

aspect of the psychosocial and

little or no understanding of highly effective local cultural healing ways that

are fully consistent with the very latest neuro-psycho-biological

understandings of the integrated function of mindbody (refer Flexibility and

Habit)

iv) Resumption of

everyday life routines as normalizing processes

This is pervasively apparent in the region

and a potent normalizing process

v) Ceremonies and

Rituals

We saw and heard

of preparations for ceremonies and festivals. One was the celebration of

Foundation day. 3,500 people were expected for the Foundation Day celebrations

at Takepan with people preparing food for shared feasts and arranged music,

dance and other festivities. Another key event is the upcoming celebrations

linking Seven Barangays in the Pikit region in a zone of peace. Other actions

have centred on children being framed as ‘children of peace.’ While it may not

be in the reader’s experience, these festivals are very complex integrated and integrating

processes holding forth promise for transforming psycho-socially. Integrating

as in the original meaning of ‘to heal’, namely, to make whole again. Within

the festival milieu, Natural nurturers may meet and form friendships with

other natural nurturers; healer

networks may emerge (Refer sociograms),

be strengthened and extended. People may have embodied experience of

being well together with others. Liminal

states may be generated. Bodyminds

may undergo transformation. Cultural

Wellbeing artistry:

(1) Art

(2) Dance

(3) Singing

(4) Puppetry

(5) Music

(6) Drumming

(7) Others

Check with NGOs –

heard many of the above to be incorporated in the above festivals and celebrations;

the above seven ways have all being used in Ernie Cloma’s work.

11) How do the local

peoples’ resilience, resourcefulness and competency manifest among the people

by gender?

a) Children

·

In their spontaneity, engrossment,

enchantment and cooperative gentle joy in play (using commonly found things).

Children have 100’s of games and often make up new games on the spot

·

In their work ethic in self-organising

cooperating in the care of their school environment – weeding, floor washing,

sweeping, rubbish collecting and the like (the school has no janitor)

·

In the Region it is often observing the

spontaneous play of children that is the impetus for healing in older people;

the children as healing catalysts

b) Adolescents and

Young adults

·

In their work ethic in self-organising

cooperating in the care of their school environment – weeding, sweeping,

rubbish collecting and the like

·

In their poised, respectful relating with

our visiting team members

·

In the Takepan high school youths joyous

spontaneous engagement in creating music, song and dance with a sub-group of

our team; their verve was palpable

c) Adults

The functional

emotional expressivity of the men in the Muslim men’s group where the merging

connecting with feelings of resentment, anger, helplessness, and grief was

explored through their storytelling and sharing of experience

d) Elderly and Old

People

Seeing the elderly

as active participants and audience in Situ meetings and discussion, engaging

in Situ chores (e.g. sweeping and cutting)

12) What are the local

ways that work in supporting people following disasters?

To reiterate,

mutual community action for wellness in everyday life

13) What are the local

ways they have used successfully in the past that they are not using for this disaster?

If some ways are specified, may any of these be fitting this time, or fitting

if adapted?

Check with the

Pikit priest, social worker linked healer networks and NGOs

14) What are the

everyday life community, village and/or clan/tribal processes and everyday

simple actions that support the re-constituting of their way of life in

wellness together? Which ones of these have been re-constituted? What others

could be re-constituted?

All of the minutia

of communal Situ and farm based life; the vibrancy of the Pikit market (watch

team safety in tight crowded places such as alleyways – have exit strategy).

Our was a medium size group of young Muslim women who were mingling in the

crowd unnoticed who suddenly surrounded us on a prearranged signal (a particular

flick of a scarf) and the circle of Muslim men parted to let us through to our

small bus.

15) Who are other

psychosocial resource people within these affected communities? For example,

teachers, social workers, traditional healers, women's associations, community

leaders, and external agencies?

(See above)

16) Who are other

local psychosocial resource people outside these communities who would be

acceptable to them; for example, skilled people from universities and religious

groups, local, nearby provinces and national NGOs?

Ernie Cloma and

his PETA associates are valuable Manila-based Pinoy resource people. The

SEA-EPSN network, UP-CIDS and the UP Psychology Department also has a number of

resource people – refer Secretariat.

17) What other

community processes, associations, networks and other social processes existed

before the emergency?

Refer 16 above

18) What community

psychiatrist, psychologists, trauma counsellors, and other mental health personnel

and actual/potential paraprofessional people are available locally or in nearby

areas who are acceptable to the local people?

Refer local Pikit

priest and NGOs.

19) What is the

general resiliency and functioning of the community?

There seem to be very good resilience.

Community life at the various levels - Situ, Barangay and local Pikit municipal

government seems alive and well. Representatives of every Situ and group

we visited except the two schools (because of previous commitment) were present

at a debriefing and feedback session about our visit held at the Takepan

Barangay Community Hall (the next building away from the road from where we met

the first two nights – opposite the Secondary School. The local women and men

each gave feedback and the team gave feedback on our observations. They said

there was not a dry eye in the rice fields because of feelings of joy flowing

from the special sounds of joy coming from our engaging with the primary school

children. This is resonant with Cambodian Cambokids and Fokkupers (Timor Leste)

experience where the healing (to make whole again) power of children’s play was

working its integral healing on adolescents and adults.

International Aid

organisations have an excellent resource on resilience in the work of Professor

Violetta Bautista and her colleagues (refer Resilience).

20) Do the communities

show cohesion and solidarity? If not,

what are the impediments? If so, how is it manifest? How may impediments be removed

and issues resolved?

Yes, they do show

both cohesion and solidarity. It is manifest in the obvious pride and passion

with which they talk about Christian-Muslim cooperation in the Situs.

Maintenance of peace between MILF and the Philippine armed forces and the

permanent cessation of redo would assist cohesion and solidarity.

Wellness Factors Related to the Various

Domains

Wellness Factors Related to Basic Survival and Needs

1) Presence of ‘Peace

Sanctuaries’, ‘humanitarian corridors’ and ‘windows of peace’ If they are not

present, what scope is there for them being established?

As stated, these

are being evolved including Children for Peace. Ernie Cloma, has taken some

adolescents from the Region to Manila to participate in a Peace Theatre Cultural Healing

Action Project with at-risk gang member adolescents from Manila and

elsewhere - and they publicly presented their output to acclaim, a fine example

of the social transforming potency of cultural healing artistry. Ernie had both

the Pikit and Manila adolescents work-shopping the development of their theatre

performance together. Manila gang members afterwards spoke of the experience of

the Pikit adolescents’ girlfriends being caught in crossfire mirroring where

they were heading if they did not stop using automatic weapons.

2) Presence of ready

access for support (airports, ports, rivers, roads, tracks)

Main Highway as a

central feature; in time of war this highway is the only access into the Pikit area and it is the focus of fighting.

This has to be considered if war outbreak is imminent or happens while in the

field.

3) What effect has

climate had on the affected people?

Occasional flash

flooding and drought add to the locals’ burdens. Flash flooding has affected

some evacuation centres. On one occasion, the evacuation centre was flooded

when the local situ people arrived and women were exhausted when NGO support

people arrive with food and water as the locals had been standing in waist-deep

water for 48 hours holding children when aid first arrived. If they fell asleep

their babies and young children would have drowned. Knowing the implications of

rain in the local context, the NGOs adapted their eclectic process so that this

flooded evacuation centre was the first visited. The head of one of the Pikit

NGOs had spoken at the Tagaytay Gathering of the eclectic nature of their Pikit

processes, where the moment-to-moment context on the ground determines what

they do next and how they do it. Any predetermined step-by-step fixed process

(set within a ten by ten excel spreadsheet) would inevitably end in a very

administratively neat profoundly inadequate mess, for example, a lot of drowned

babies and children and bereaved mothers, fathers, friends and distraught

communities.

4) Detail security,

nature, amount and continuity of food supply; food sources and supplies, recent

food distributions, and future food needs and availability

Currently there is

a cessation of hostilities. Food is available and much of it is locally grown

(rice the main local crop), community and family vegetable plots, chickens and

the like.

The Pikit Catholic

Church group seems to have a transparent accountable food distribution system.

The Pikit priest was prepared to make strong requests for cooperation by the

army to allow free access of food deliveries. He would also put his life at

risk to take on specific humanitarian actions. For example, under white flag

going and picking up a couple hiding by the roadside who had not made it to the

evacuation centre.

5) Availability and

quality of clothing, bedding and shelter

Check local NGOs

6) Adequacy of

sanitation

Some questions were

raised – especially adequacy of water for cleansing following visits to

toilets. Difficulties women had regarding personal hygiene discussed in Muslim

women’s group.

7) Detail the

availability of transport, fuel, communication, and other logistic necessities

for wellness in the affected area

Check with NGOs

8) Morbidity, death

rates, and causes (by age and gender).

Check with NGOs

9) Presence or

likelihood of Infectious disease

Understand that

there are none at present – check with NGOs

10) Issues created by

mosquitoes and other pests and illness sources

Few mosquitoes at

present though a sleeping net is advisable

11) What sources of

harm continue to exist?

Rogue elements,

kidnapping, and possibility of breakdown of the peace talks; redo related

strife.

12) What is the supply

and quality of water?

Local spring water

seems good. As we were staying with host families we bought bottled water for

our needs at Cotabato

13) Other basic

survival needs in order of priority

·

Phone numbers of local NGO contact people

·

Food,

·

Torch, and matches to make brush fire

torch if caught outside

·

Appropriate Evacuation Plan that everyone in the team knows

·

·

Care re Cobras (on lawns near houses)

·

Travel with known locals organised by the

NGOs or the Pikit priest, especially in Pikit Market

·

The Pikit priest is a good entry point to

first engaging with the military

Wellness Factors Related to Economic Aspects

1) What economic

structures did they have? What kinds of production and handling of resources at

family, district, camp, and country regional levels? How may these be improved

or re-constituted?

Discuss with local

NGO

2) Is there unequal

distribution of resources and benefits by:

a) ethnic, political,

or other kind of grouping

Steps are taken to

ensure actual and perceived equality as this can be a major source of strife.

3) If so, how may

these matters been improved?

Processes are

being refined in talks between the local government social workers and the

Pikit priest’s group and others.

Wellness Factors Related to Education

1. Are there teachers

among the affected communities?

Yes. The

elementary school – indicative of the region – is well below national averages

in basic competency levels. Short term funding is allowing catch-up classes on a

Saturday morning for some months. The schools lack teaching resources suitable

for Islamic and Lumad culture.

2. If so, how are

they being used? How could they be better used?

Normal roles.

There was evidence that the curriculum and resources for the year ten Arts and

Community Development subject were culturally inappropriate for rural

tri-people communities. Culture and locality specific resources could be

developed (a job for PETA – Ernie Cloma’s group?).

3.

Specify any formal or informal educational

activities, including extracurricular ones that exist among

a. the affected

people

b. refugees

c. displaced

communities

d. war-affected

communities

The normal school

curriculum is functioning

4. If education is

taking place, how adequate is it?

Suspect the whole curriculum

could be checked for cultural and intercultural appropriateness and to

determine how well it prepares children for local life and job opportunities

Wellness Factors relating to Habitat

1) What has been the effect on housing and

habitat?

Some housing destroyed and replaced. One

family who had experienced substantial damage to their concrete home a number

of times elected to destroy it and build a home from local bush materials.

There’s a gaping hole in one school

building – an ongoing reminder of shelling.

Given that the children had experienced

the stress of repeated hostilities sitting on the playground of their primary

school it was a joy to see them so engrossed in joyous play when we were

engaging with them on the same ground

– the meaning reframing of the