|

CHAPTER FOUR - FRASER HOUSE EVOLUTION AS

AN INEVITABLE CONSEQUENCE

CHAPTER FOUR - FRASER HOUSE EVOLUTION AS AN

INEVITABLE CONSEQUENCE A SOCIAL MODEL OF MENTAL DIS-EASE AND CHANGE TO BEING

WELL Assuming A Social Basis Of Mental Illness LAYOUT, LOCALITY, AND CULTURAL LOCALITY Locality As Connexion To Place And Connexity With Place Aboriginal and Islander Patients Fraser House As Therapeutic Community The Far-From-Equilibrium Learning Organization Socio-Medicine For Social Cohesion - Everyday Life

Milieu Therapy Handbooks On Fraser House Structure And Process SELF-GOVERNANCE AND OTHER RECONSTITUTING PROCESSES The Resocializing Program – Using Governance Therapy Patient Treatment And Training The Domiciliary Care Committee The Outpatients, Relatives And Friends Committee Constituting Rules And Constitutions The Roles of the Patient Committees The Canteen And The Little Red Van Saying ‘No’ And Undercontrolled Auditors DIAGRAMS DRAWINGS Drawing 1 The metaphorical normal middle FIGURES Figure 1 Categories in which Neville sought to have

equal numbers of

Patients PHOTOS Photo 1 Neville and nurse at Fraser House Photo 3 Fraser House along Keyline where the convex

curve becomes concave Photo 4 One Wing of the Fraser House Dorms Photo 5 Allocating the job to those who can’t do it SOCIOGRAMS ORIENTATING

This

Chapter is the first of four on Fraser House and commences with Neville’s

adaptation of his father’s Keyline to Cultural Keyline within the context of

evolving Fraser House, a psychiatric unit that opened in 1959 within North

Ryde Hospital in Sydney, NSW. The Unit’s processes assuming a social basis of

mental illness, and Fraser House locality, cultural locality, layout and

sourcing of patients are discussed. An overview is given of the Unit’s milieu

and Neville’s processes for evolving it as a therapeutic community. The

Chapter concludes with a description of the Re-socializing Program entailing

patient self-governance and law/rule making via patient-based committees. In

the forward of Clark and Yeomans’ book about Fraser House, Maxwell Jones, the pioneer

of therapeutic communities in the United Kingdom wrote, ‘Throughout the book

is the constant awareness that, given such a carefully worked-out structure,

evolution is an inevitable

consequence’ (Clark and Yeomans 1969) (my italics). The reasons for

this comment by Jones about Fraser House are discussed in the next

four chapters. A SOCIAL

MODEL OF MENTAL DIS-EASE AND CHANGE TO BEING WELL

Window Of Opportunity

Neville

had completed degrees in zoology, medicine and the further studies to become

a psychiatrist in the mid Fifties. In 1956, three years prior to setting up

Fraser House, Neville initiated the first group psychotherapy program for

schizophrenics in Gladesville Hospital (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 12, p. 66-69).

Neville recognized that, with considerable upheaval and questioning in the

area of mental health in New South Wales, and a Royal Commission being mooted

into past practices - there was a small window of opportunity for innovation

in the mental health area. The New South Wales health department built the

Fraser House residential unit especially for Neville. Neville was aged

thirty-one when he obtained the go-ahead from the New South Wales Health

Department to take in patients at Fraser House, a psychiatric Unit located in

the grounds of North Ryde Hospital in Sydney, New South Wales - now called

the Gladesville Macquarie Hospital. The Fraser House men’s ward was opened in

September 1959 and the women’s ward in October 1960. Fraser House was a 78

bed and 8 cot short-term government hospital for voluntary severe

psychiatric people; psychotics, schizophrenics, psycho-neurotics, and people

with personality disorders. This Unit was established from outset as a therapeutic

community, with Dr. Neville Yeomans as founding director and psychiatrist.

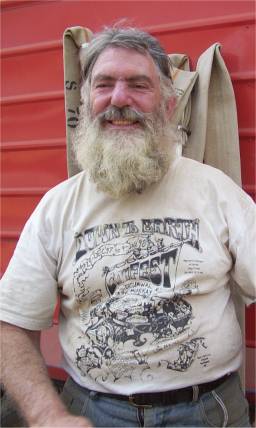

Photo 1 Neville and

nurse at Fraser House Assuming A Social Basis Of Mental Illness

Neville evolved Fraser House assuming

a social basis of mental illness. Consistent with this, the treatment was

sociologically oriented. It was based upon a social model of mental dis-ease

and a social model of change to ease and wellbeing. Neville and

Fraser House worked with the notion that the patients’ life difficulties were

in the main, from ‘cracks’ in society, not them. Neville was familiar

with twin sociological notions that people are social products and at the

same time people together constitute their social reality (Berger

and Luckmann 1967). Neville took as a starting

framework that a person’s internal and external experience, along with

interpersonal linking with family, friends and wider society all have

connexity. Given this, Neville held to the view that pathological society,

pathological community, and dysfunctional social networks give rise to

criminality and mental dis-ease in the individual. As well, his view was that

‘mad’ and ‘bad’ behaviors emerge from dysfunctionality in family and

friendship networks. Problematic behaviors may be experienced as feeling bad

or feeling mad, or feeling mad and bad. For these people, life may be lived

as unfathomable mess. While Neville recognized massively interconnected

causal process were at work, he also recognized and emphasized this macro to

micro direction of complex interwoven causal processes within the

psychosocial dimension. Working with the above framework Neville set out to

use the Keyline principle, ‘do the opposite’ to interrupt and reverse

dysfunctional psychosocial and psychobiological processes. Neville told me a number of

times that the aim and outcome of Fraser House therapeutic processes was

‘balancing emotional expression’ towards being a ‘balanced friendly person’

who could easy live firstly, within the Fraser House community, and then in

the wider community. The process doesn’t require or need ‘intellectual’

therapy. In this there is resonance between Nevilles and Assagioli’s thinking

(Assagioli

1971). Neville’s view was that the

intellect is the ‘servant of emotions’ and ‘servant of reproductive and

survival instincts’. Many Fraser House patients returned to functionality

with little by way of insight about what had happened to them. Neville said

that what they were researching at the Unit was whether sharing everyday

Fraser House milieu would lead to emotional corrective experience and a move

to functional living in the wider society. Neville

wanted to create a special place where people could evolve their own way of

life – their own culture – together; where they could evolve themselves as

they evolved their shared reality. This follows

from Neville’s ‘interconnected living system’ view on embodiment outlined in

Chapter Three, namely that our ideas, processes and actions with others in constituting

shared realities may sustain and change the way our body functions, and

simultaneously the way our body functions may sustain and change our ideas,

feelings processes and actions. While all manner of things

were awry with patients – cognitively, mentally, physically, emotionally, and

socially – within the Fraser house milieu, all structure and process framed

and actuated the ‘community’ as the central transforming process in the

therapeutic community, regardless of a patient’s presenting condition and

conventional diagnosis. LAYOUT, LOCALITY, AND CULTURAL LOCALITY

Locality and Layout

Fraser

House was a set of buildings over a quarter of a kilometer long. The buildings were set in a long thin wiggly line along

the contour line - refer map below. From my reckoning, the building is along

a Keyline, and Neville’s office was at the Keypoint. I had already noted this

when in 2001 Jack Wells, who is familiar with Keyline and worked at Fraser

House in the early 1970’s after Neville had left, also pointed out to me the

Keyline connection in the Unit’s layout. I met Wells through a conference

festival that Neville helped evolve called ConFest. This Conference Festival

is discussed in Chapter Eight.

Photo 2 Jack Wells at

ConFest

Photo 3 Fraser House

along Keyline where the convex curve becomes concave The

buildings were linked by enclosed walkways. While Fraser House was specially

built for Neville, he had no say in aspects of the design layout. The Health

Department ‘system’ required complete separation of males and females in

different wards. A single story administration building was in the middle. At

one end of the central administration section was a meeting room

(approximately eight meters by sixteen meters) where the big meetings were

held.

Diagram 1 Map of section of

Gladesville MacQuarrie Hospital,

(formerly North Ryde Hospital) showing Fraser House, made up of Wards

8 & 9, now called the Lachlan Center At either end of the administration block there was a double

story 39 bed ward, and there was a dining room at each end. There was a

separate staff office in each ward. Most rooms were 4 bed dormitories. There

were a few single rooms in each ward. In Fraser

House, the State system’s intention to have a division of sexes in separated

wards would have been ‘shattering’ any chance of what Neville called ‘total

community’, ‘transitional community’ and ‘balanced community’. Neville viewed

the original planned (by the system) use of space as ‘schizoid’ - completely

divisive, split - creating ‘them and us’ and ‘no go’ areas for both patients

and staff. Neville saw this separation of the sexes as isomorphic with

cleavered dysfunctional community. Warwick Bruen was a psychologist at Fraser

House in the early 1960’s. In a 1998 interview, Bruen described the initial

separation of sexes into different wards required by the Department as, ‘an

extension of the medical infection model’.

Photo 4 One Wing of the

Fraser House Dorms The

female ward opened in October 1960. Neville rearranged room allocation so

there were no separate wards for males and females, although bedrooms

remained same sex. This required some negotiating between Neville and the

male staff and Unions as there was resistance to this change. After the Unit

was running for a time, eight downstairs rooms were set aside for

families-in-residence. The eight cots were also in these rooms. School age

child patients at Fraser House attended local schools. Neville

arranged for the dining room at one end to be used by all patients. The other

dining room was turned into a TV, games and recreation room. This created the

necessity for patients and staff alike to walk more than quarter of a

kilometer wending through each building and along winding covered walkways

between buildings to go to these popular places. The dining room, the lounge

room and the long corridor between them were all public spaces conducive to

meeting and talking. Fraser House was a replication

of the community space of the Tikopia Villages and trails. Locality As Connexion To Place And Connexity With Place

The

following is a synthesis of my crosschecked findings from interviewees and

archival records. Neville created opportunities for Fraser House residents to

respect and celebrate their diversity in creating social unity and cohesion

as the Fraser House Community. While Fraser House was located in the

grounds of the North Ryde Hospital, Neville was creating locality in the sense

of ‘connexion to place’. He structured interaction such that the close

communal living and the mores they evolved together helped constitute and

sustain individual and communal psychosocial wellbeing among the residents.

Neville also structured interaction during Fraser House events, and outdoor

picnics and excursions (Fraser House Follow-up Committee of

Patients 1963). Just as in Tikopia, Neville

structured social exchange such that psychosocial wellbeing processes were

woven completely into every aspect

of their lives together. There was constant linking within and between people

of differing generations, gender, ‘clan’ (family group), ‘village’, home

locality, status and occupation (that is, differing sociological categories).

Neville did this by cleavering the Big Group attendees into the Small Groups,

each time using different sociological categories. This is discussed in

Chapter Five. In Fraser

House, everyone’s lives in the Unit’s space created public space. The Unit’s

public space was community space - where people were in continual close

social exchange - where friendships blossomed and were sustained by regular

contact. Neville created Tönnies' ‘Gessellschaft’ (Tönnies and Loomis

1963). Like in Tikopia, with

all of the constant social exchange, any strife soon became common knowledge

and typically, it was interrupted before it could start. Within the wider

civil society there is scant ‘public space’ as places that allow for, and

foster people engaging in conversing and community building with friends,

relatives and strangers. The shared community life in Fraser House ‘public

space’ meant that people continually talked to and about each other, and

hence, like on Tikopia, social news was continually circulating. In Fraser

House this circulating of social news was encouraged by the slogan, ‘bring it

up in a group’. At certain

times of each day there was a mingling flow of females and males from one end

of Fraser House to the other along a winding long

passageway that mirrored the mountain trails between both sides of Tikopia

Island. In Fraser House everyone was ‘contained’ within healing

community space. Everybody was in every one else’s gaze, and audience to each

other’s change work. Chilmaid made the observation in April 1999 that there

was literally no place to hide in Fraser House. One swoop through the place

would find someone if they were there. Neville

created a large community gathering place in Fraser House for Big Group

Meetings and many smaller gathering places for Small Group meetings and

re-creation, with the passages between these (and the dining room) mirroring

Tikopia trails. In evolving Fraser House, Neville engaged in place-making and

sub-place-making. For example, the room that Big Group was held in became a

very special place. Neville set

up a process where there was always a support network to call on to resolve

any issue. As necessary, a special support network would be temporarily

created to surround one or more till an issue was resolved. For example, in

Fraser House suicidal people would have a small 24 hour-a-day support group

comprising patients and staff. The Unit’s evolving common stock of practical

wisdom about what works was so readily passed on that this wisdom was widely

held in the Fraser House community. Patients, Outpatients and staff who had

been in Fraser House for a time knew ‘what worked’ in different contexts.

These socio-healing actions were preventive. They sustained wellbeing. They

were the norm. Social exchange that ‘worked’ constituted an integral part of

the patients, outpatients and staff’s evolving good life together. Typically

it was trivial ‘everyday stuff’ about how to live well together. Like

in Tikopia, within Fraser House Neville structured it so that people lived

with those most different to themselves. The under-active

over-controlled shared dorms with the over-active under-controls. As in

Tikopia they lived with those most different in order to gain unity and

strength together though regular contact in day-to-day life. All involved in

Fraser House experienced inter-related cohesive factors of everyday

operation, the use of a common understanding and experience of Fraser house

routines and shared values, and the sharing of a common culture; the sharing

of Community (with a capital ‘C’), - to paraphrase Firth - all that is

implied by all involved in the Unit when they would speak of themselves as

‘being at Fraser House’, just as the Tikopian said ‘tatou na Tikopia,’ ‘We

the Tikopia,’ Locality

as ‘connexion to place’ became ‘connexity with place’ by Neville’s modeling

and by osmosis as all aspects of Fraser House’s social forces naturally

constituted interdependent, inter-related, interwoven, inter-connected, and interlinked

experience and action. While I can write about this, to fully

sense Fraser House we would have had to have been there; words are not up to

the job – like attempting to convey with words the lived experience of

listening to Bach’s Mass in B Minor. All the above is discussed in greater

detail in this and later Chapters. Cultural Locality

Crosschecked

interview reports from all of my Fraser House interviewees and findings from

a wide range of archival material (Yeomans 1965; Yeomans 1965; Yeomans

1966; Yeomans 1967) confirm that the Fraser House

milieu became a community of people who were evolving their own sub-culture

together. While all people do this all the time, Neville recognized that

linking people together, and simultaneously linking them to a specific place,

has potential. In the last Chapter I referred to this as creating ‘cultural

locality’ (Kutena 2002). Neville used the word ‘culture’ as

meaning ‘way of life together’. He used the word ‘locality’ having this

meaning in his drafting of the Objects of the Keyline Trust mentioned in

Chapter Eight. In specifying things being produced by the Keyline Trust

Neville wrote: (b) Such materials and productions to be Australian in origin and dominantly for the purposes of enhancing community cooperation and mutual support, locality, self respect, friendliness, creativity, culturally appropriate peaceful nationalism and multinational regional cooperation Recall that ‘Cultural

locality’ means ‘way of life together in this place’. ‘Cultural locality’ is

derived from Indigenous sensitivities, wisdom and way. While Neville used the

term ‘locality’ to mean ‘connexion to place’ I cannot recall him using the

expression ‘cultural locality’, although I sense he would have had resonance

with this expression. All people involved in the Unit belonged to and were

together evolving the Fraser House cultural locality. The places and spaces

in Fraser House became very familiar. They were intimately known. These

spaces and places, as well as the staff, outpatients and staff in those

spaces and places were all an integral part of it. Once oriented

participants in the Unit knew where they were within Fraser House. This was

in a twofold sense, firstly, where they were in Fraser House space, and

secondly, something far more challenging, where they were in relation with

all the others in the Fraser House community. They also knew where they

were in relation to other places and spaces in Fraser House. All of this was

embodied. They had feeling and knowings and associated shared understandings

of the past happenings in Fraser House places and spaces. Their mindbody

‘livingness’ – as in ‘the whole of it’ (Kutena 2002) responded to the re-membering of

these happenings. All involved were living the physical embodiment of the

Fraser House cultural locality. By arranging for all in Fraser House to

attend Big Group meetings Neville was creating concentrated cultural

locality. The vibrant cultural locality of Fraser House was vastly different

to the anomic, displaced, normless, alienated, unconnected, meaningless,

overwhelming, aggravating lives they had been leading. EMBODYING KEYLINE

The

Tikopia people, in communally walking against and with gravity as they walked

over the ridges to an fro - passing those opposite to themselves in friendly

banter - were embodying their way of

life - a mindbody synthesis with their people, their place, and their world.

Like the Tikopians, all in walking to and thro in Fraser House were embodying their way of life - a

mindbody synthesis with their fellow Fraser house people, in their place and

in their world of their co-reconstituting. For

Neville particularly, ideas, feelings, bodily functioning – even down to the

neuro-psychobiological dendritic and cellular level, as well as psychosocial

processes and actions in everyday life are all interactive and

co-constituting, that is, each part plays a part in maintenance and change

processes. This is discussed in Chapter Six. Resonant with Neville’s view on embodiment, Stephen

Rose, author of the Conscious Brain (Rose 1976; Rose 2002) in a radio interview broadcast on the Australian ABC Science

Show on Saturday 29 June 2002 said, ‘Changes in Society can change people’s

nature, which in turn can change their biology’. Neville would have said that

change in any of these three aspects might ripple through to change the

others. This has important implications. Our ideas, processes and actions

individually and collectively may sustain and change the way our body

functions. The way our body functions may sustain and change our ideas,

processes and actions. Another term for ‘embodying’ is ‘incorporating’ from

the Latin ‘in corpus’ meaning, ‘in the body’. This embodying has been

intimated a number of times already. Neville was constantly exploring how to

foster and use this interactive embodiment

happening within and between connected people who are connected to place

– cultural locality. Fraser House people incorporated Fraser House Way. This extends ideas discussed by Berger and Luckmann that society is

social constituted and in this process - people are constituted as products

of society, psychosocially, and psychobiologically

(Berger and Luckmann 1967). Recent research into tensegrity (integrity through tension) (Buckminster Fuller 1961; Pugh 1976) and intercellular communication is resonant with this. The creative

and strategic use by Neville of tension to enable integrating possibilities

(tensegrity) in Fraser House will be introduced in Chapters Four through

Seven. Neville’s use of ‘extegrity’ (Yeomans 1999), a term he used meaning ‘extensive integrity’ in Laceweb peacehealing

for reconstructing collapsed societies is discussed in Chapters Nine and Ten.

SOURCING PATIENTS

Back Wards and Prisons

It

was not commonly known in 1959 and through the Sixties that Neville set up

Fraser House to be a micro-model of a dysfunctional world and more

specifically, a micro-model of the alienated dysfunctional fringe of a

dysfunctional world. This was the major first step in exploring epochal

change. This was where Neville felt it was the best possible place to start.

What’s more it was Neville’s view that together, this fringe had massive

inherent potential to thrive. This was isomorphic with nature’s tenacity

to thrive at the margins. Neville’s aim was to work with and tap this potency

just as he and his father worked with the emergent potential of their

farmland. His relation to the land and to this alienated dysfunctional fringe

was one of love, care, respect and awe at their potential, rather than one of

disdain, domination and control. Neville was mirroring Indigenous way. To

approximate this alienated fringe, Neville arranged to populate the Fraser

House with a balanced group of ‘mad’ and ‘bad’ people. To reiterate for

emphasis, Neville was not just setting himself a big challenge in starting

with the mad and bad of Sydney, he did so because he firmly believed that

these, along with dysfunctional Aboriginal and Islanders were the best

people to work with in evolving a new caring epoch Fraser House accepted long-term chronic mental patients and

other severely mentally ill people balanced with an equal number of

criminals, alcoholics, delinquents, addicts, and according to the sexual

mores of the Sixties, homosexuals, prostitutes and other sexual deviants (Yeomans 1961; Yeomans 1961; Clark and Yeomans 1969). There was a spread across the various diagnostic categories.

The intake aim was to have a spread of categories present in the Unit.

Appendix 3 shows the various categories of patients in Fraser House as at 30

June 1962. Note that there were an equal number of males and females. This

was typical From

the outset Neville negotiated with the Office of Corrections that Fraser

House would have twenty male and twenty female prisoners released on license

to Fraser House at any one time. People were transferred straight from jail

and signed on as voluntary patients. None of the Wards at Fraser House were

locked. Few absconded. If they did, they knew that Neville would send the police

after them. Upon their return to Fraser House they would face the possibility

of not being able to stay and therefore the aversive possibility of being

transferred to another hospital, or for ex-prisoners, being transferred back

to jail with further charges against them. The

prisoners selected to go to Fraser House typically had considerable

psychosocial dysfunction that had been in no way addressed by incarceration.

They were typically in the last months of their prison term. Typically, that

some of them had to be soon

released back into society was a worry to people at all levels of society. Fraser House patients were adults, teenagers and children of

both sexes, mainly from middle and working-class backgrounds. Typically,

around two thirds of Fraser House patients were referred from public

agencies, especially state Psychiatric Services. Other institutional

referrals came from courts, probation and parole services, and the narcotics

and vice squads. Some admitted were referred by private individuals, doctors,

patients and staff (Clark 1969, p.58-59). Some staff admitted themselves as voluntary patients. In

1961, referrals were accepted from patients, and family and friends were

admitted. In 1963 whole families were admitted. Desegregation of family units

and single patients occurred in 1964. (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 4 p. 2-4). During the development of Fraser House in 1959 the working name

for the Unit was reported in the Weekender Newspaper as the ‘Neurosis and

Alcohol Unit’. Neville was reported in the Sunday Telegraph Newspaper, 14

February 1960 as saying that he believed that Fraser House was the only

clinic in the World where Alcoholics and Neurotics mingle 50% and 50 % (1960, February 14). The male Unit had both single and married men. Married men who

were alcoholics could have their wives stay with them regardless of whether

the wife was an alcoholic or not. The couple was the focus of change. This

was the start of eight family suites. Whole families with two and three

generations, from babes in arms to the elderly were involved in the suites.

Neville pioneered family therapy and inter-generational therapy in Australia. The focus of change at Fraser House for both the mad and the bad

was ‘the patient in their family-friendship-workmate network’. In keeping

with this, another condition of entry was that members of a patient’s family

friend workmate network had to sign in as outpatients and attend Big and Small

Groups on a regular basis. According to all of my interviewees, including a

former patient and outpatient, the Fraser House outpatient sub-community was permeated with

dysfunctional/problematic behavior, which was typically transformed to

functionality by their involvement in Fraser House. It was regularly found

that dysfunctional patients had dysfunctional family-friendship-workmate

networks. The focus of change being the patients and outpatients and their respective networks made

sense from the Fraser House experience. In supporting mad and bad people to live well with each other,

Neville’s view was that one of the primary healing processes that was both

structured into and continually and pervasively at work within Fraser House, was

the day-to-day lived-life dynamic healing interplay of social cleaving and unifying processes; the

same processes that have been discussed in talking about Tikopia. Neville

would set up scope for micro-experiences creating very strong forces cleaving

pathological entanglements, as well as forging functional bonds within

and between people - linking them back to their humanity. Balancing Community

Resonant with Tikopia and as part of Fraser House’s Unity

through Diversity, Neville arranged for Fraser House to be a ‘balanced

community’. Neville endeavored to have equal numbers in each of a number of

categories. Neville sought and obtained balance within the Unit population on

the following characteristics: ·

inpatients and outpatients ·

mad and bad ·

males and females ·

married and single ·

young and old ·

under-active and over-active ·

under-anxious and over-anxious ·

under-controlled and over-controlled Figure

1 Categories in

which Neville sought to have equal numbers of Patients Neville

in his paper ‘Socio-therapeutic Attitudes to Institutions’ refers to the potency of community

process in the ‘balanced community’ he had created. He speaks of a special

kind of community as a therapeutic technique, where, ‘therapeutic

techniques must aim at giving patients autonomy and responsibilities, and to

encourage contrast with (the wider) community, the ‘balanced community’ aims

for a mixture of patient types so that the strain is towards normality rather

than the strain toward the mode of abnormal behavior of a particular section

of the institution’ (Yeomans 1965, Vol 12.

p. 49). The above quote is another example

of the way change was structured into the Fraser House process. The emergent

properties of social and community forces were recognized and harnessed. In

his monograph, ‘Social Categories in a Therapeutic Community’ (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 2 p. 1) Neville describes a

number of processes used to allocate beds : age grading, marital status and

social categories. Room allocation was never based on diagnosis. While there were same sex dorms (except in the family

units) Neville ensured that the opposites were placed together in dorms,

therapy groups, activities and patient-based committee work. An example of

structured use of cleavage/unity processes in Fraser House was allocating

bedrooms such that two under-controlled hyper-actives (e.g. sociopaths) were

placed in with two over-controlled under-actives (e.g. neurotic depressives).

This became the main basis for room allocation. Many interweaving processes, to be discussed later, ensured

patient safety. Having opposites sharing the same dorm was based on the

principle that the presence of opposites creates a metaphorical normal

position in the middle. Fraser house research showed that there was a

tendency towards the mean, with under-controlled becoming more controlled,

and less active; the over-controlled became less controlled and more active.

Drawing 1 The metaphorical

normal middle A

‘glimpse’ of Neville’s use of the above two principles and Tikopia’s

cleavered unities show up in the book, ‘Fraser House’ under the subheading

‘Cleavages’ (Clark and Yeomans 1969, p. 131). ‘The

friendship patterns, and therefore the informal influence structure,

reflected cleavages in social groupings according to status (patient or

staff) and sex. This conclusion is based on a sociogram, figure 14.1

constructed from replies to the question’ ‘Who are your main friends in the

Unit?’ ....’

Sociogram 1 This sociogram

is Figure 14.1 from Clark and Yeomans, 1969 book depicting a sociogram

of Mutual Choice Friendship Structure ‘In the

sociogram, a horizontal line shows

the cleavage between staff and

patients, and a vertical line shows

the cleavage between the sexes’ (my

italics). The

authors summarize the sociogram data as follows, ‘In short,

the genotypical structure of the community

(my comment: ‘as a healing community’) is represented by the mutual ties that

form a network which is both continuous

and yet divided by sex and

staff-patient status (my italics).’ One

observation of the emerging community depicted in the above sociogram is the

relationship between the informal and the formal social structure. Clark and

Yeomans provide the following comment on this: ‘The individuals with the most formal power

are the psychiatrist in charge (Neville) (40) and the medical officer (41),

the male charge nurse (23) and the female charge nurse (11). Of these, the

only one with a link, by means of a mutual tie, into the genotypical informal

social structure was the psychiatrist in charge. This suggests that the main

burden of influence and communication falls on the lower status individuals.’ This

finding is fully in keeping with Neville’s notion of devolving responsibility

and reversing the status quo. It was also in keeping with Neville’s hands-off

though being profoundly and sensitively linked that he was enabler on the

edge of the informal social structure. Recognizing the inter-generational nature of dysfunction, Fraser

house had three generations of some families staying in the family units or attending

as outpatients. There were three types of inpatient categories - firstly,

inpatients who attended each day from 9A.M. to 9 P.M.; secondly, residential

inpatients who went out to work full-time or part-time; and thirdly,

full-time residential inpatients. Fraser House

was a huge endeavor. Once under way it was having around 13,000 outpatient

visits a year. Big Groups and Small Groups were held twice a day on all

weekdays with between 100 and 180 in attendance five days a week year round. Fraser

House had more than 3000 small groups a year with between 8 to 12 people

attending, i.e. between 24,000 and 36,000 people attendances (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4 , p. 18) For all of the unifying talk within Fraser House of, ‘we are all

co-therapists’ - staff and patients alike - when a member of staff required

treatment it was given in groups containing only staff members, or the

treatment was given separately from the day-to-day functioning of the unit,

or the staff member gave up the staff position and signed in as a patient.

Some staff did do this. Aboriginal and Islander Patients

In keeping with his (Yeomans 1965) interest, one of the early things Neville did was to invite

Mental Hospitals throughout NSW to send any Australian Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander patients that they had incarcerated to Fraser House. The 9

April 1962 Daily Mirror ran an article with the heading, ‘NSW Lifts the

Aboriginal States – Freedom in Ryde Clinic’ (1962) wherein Neville is quoted as saying, ‘We have a plan to

transfer to the Centre over a period of time all 50 Aboriginals who are now

patients in NSW mental hospitals.’

Around Fifty Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients

were sent to Fraser House, emptying all the other Mental Hospitals of

patients with these backgrounds. Apart from a few that needed full time care because of

associated medical conditions, all of these Aboriginal and Islander people passed

through Fraser House and were returned to their respective communities. Both

Bruen and Chilmaid, as well as media reports (Yeomans 1965) confirmed that these patients blended into and participated in every

aspect of the Fraser House healing milieu. The 9 April 1962 Daily Mirror

article mentioned above also stated: ‘Aboriginals mix freely with white patients in a special unit at

the North Ryde Psychiatric Clinic. It is the first time in NSW that Aboriginals

have been accepted with equality in a psychiatric unit. They share the same

wards and have the same privileges as white patients’. Neville is reported as saying, ‘One Aboriginal patient at a

mental hospital for 20 years had been completely rehabilitated after a few

months at the center. He is now at home with his family.’ Margaret Cockett would continually ask around the prison/court

system for any Aboriginal and Islander people who could be transferred to

Fraser House. Typically, the people involved in the prisons were pleased to

let Aboriginal and Islander people transfer. One such Aboriginal prisoner was

paranoid as the reason he was in jail was that whenever he was drunk he would

go out of his way to punch policemen. He settled down in Fraser House and was

released to more functional living with his family. As

an example of a back ward individual, Neville described the case of an

isolate micro-encephalic Aboriginal person (born with a very small brain) who

presented with few skills. He had the body of a twelve year old though he was

an adult. He had no capacity for speech and would make aversive noises, for

example, snarling and screeching. As well, he would get angry and bite.

Within the Unit, at Neville’s instigation, this person was related to as if

he was a ‘lovable little puppy dog’. This matched his optimal functioning.

After this he soon became friendly, contented and easily fitted in to Fraser

House society. Neville described his cries as: ‘…soon becoming harmonious and

naturally expressive of mood - typically, contentment and happiness compared

to the prior screeching. He had probably moved close to the optimum

functioning of his mindbody. Thereafter he was attached to various factions.

He was able to move back out into the community in a care-house and fit in

with the house life as a normal micro-encephalic person rather than a

dysfunctional abnormal one’. Neville

was fascinated that this person adjusted so well to social life and his

change was a convincer for Neville that emotional freeing up is the core of

all therapy. ‘With no frontal cortex to speak of, how else could he have

changed?’ THE FRASER HOUSE MILIEU

Creating Whirlpools

Both psychosocial structure and

processes where entangled in Fraser House just as the. whirlpool’s structure

only exists as water in process in a vortex. Similarly Fraser House’s tenuous

evolving psychosocial structure was constituted, reconstitured and sustained

as self-organising human energy - as processes in action. Being Voluntary

While many

of Fraser House patients were people who had been committed to other asylums

and required approval of the system to leave, a condition of entry to Fraser

House was that patients voluntarily accept

the transfer to Fraser House with some appreciation of what the Unit was

like. Having all patients

‘voluntary’ was part of the self-help frame Neville set up at Fraser House.

This ‘voluntary’ component was a crucial aspect of patient empowerment.

Neville saw the Health Department stopping this voluntary requirement in the

late Sixties as the single most important imposed change that ended Fraser

House as self organizing Cultural Keyline in action. This is discussed

further later. Neville

asked around Mental Asylums for people they had in their back wards. These

wards were typically where ‘long term stays’ were kept who the system had

given up on ever restoring to society. Eleven certified patients from

Gladesville Hospital’s back wards were asked, and Neville described them as

more in the ‘resigned to coming’ category. They were given ‘Special Care

Leave" from their home hospital and signed on

as patients at Fraser House. Neville said that apart for a couple who had

serious medical problems who needed constant care, the rest of these moved

through Fraser House and back to functional living in Society. Re-Casting the System

There

is present in society a caste system that says, ‘normals have to behave

normally, criminals behave criminally and mad people are anticipated to

behave madly’. One psychiatric nurse with experience outside of Fraser House

said that in her experience of other mental asylums, both the patients and

the staff will tolerate madness in other patients, ‘because the patients are

ill’. However, they typically will not tolerate the slightest bit of

inappropriate behavior in staff. This again reflects the caste system. When I

mentioned her comments to Neville. his view was that while this ‘tolerance’

towards patients in other institutions in one sense is ‘showing consideration’,

at the same time, this tolerance maintains the madness. In Fraser House there

was relentless subversion of both madness and criminality, and rather than

displaying a tolerance that maintained the status quo, fellow patients took

the lead in this subverting. Some people in some categories of mental

disorders were inept in picking pathology. Other patients and outpatients

became very skilled at picking pathology or were already skilled at this and

took the lead in pointing out, ‘that madness and badness are not tolerated

here’. In Big

Group, and in other Fraser House contexts, people would be engaging in all

the ‘natural’ dysfunctional roles of ‘helpless’, ‘hopeless’, ‘blamer’,

‘judger’, ‘condemner’, ‘distracter’, ‘demander’ and the like. For a

discussion of these terms refer Virginia Satir’s books (Satir 1972; Bandler, Grinder

et al. 1976; Satir 1983; Satir 1988). Typically, some of the

patients using these behaviors would be withdrawn isolates. Anyone using any

of these behaviors in Fraser House would have had it pointed out to them and

typically, they would have been interrupted. If they persisted in the

behavior this would have been reported to Big Group and Small Groups. This

is another example of Neville’s use of his father’s idea of using ‘opposites’

and ‘reversals to mainstream protocols. When madness or badness was subverted, all hell may break

loose, and Fraser House had the processes to work with the corrective

emotional outpourings and experience, and the support for people through this

experience, towards functionality. Getting On With It

Recall

that from inception, Neville had teed up Fraser House as a ‘short term stay’

facility. For Neville, Fraser House was not an interim ‘holding place ‘ while

a long term place could be found in other institutions. From the outset

Neville had confidence that his ideas would work in getting people living

functionally in the wider community. A rule was set up that patients could only stay at Fraser House for six months.

This was later reduced to three months. After three months patients had to

leave regardless of whether they had improved or not. This rule was to

provide motivation to ‘get on with their healing’. The clear message of the

rule in the vernacular was, ‘Don’t procrastinate. Get on with it.’ At one

time the typical stay was six weeks (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 4 p. 2-4). Another general rule on admittance was that patients could return

to Fraser House three times. The break between returning was flexible. One

patient said that he wanted a transfer to Gladesville Hospital. He was told

that on leaving Gladesville he could not return to Fraser House for six

months. He did go to Gladesville for a short time and then settled down and

got on with his healing at home. This was reported to Neville by patients

doing follow-up domiciliary work – (from conversation with Neville during

Aug, 1999). This follow-up work is discussed later in this Chapter. Fraser House As Therapeutic Community

In

Neville’s paper, ‘The Psychiatrist’s Responsibility for the Criminal, the

Delinquent, the Psychopath and the Alcoholic’ (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 12, p. 50)

he wrote, ‘The community is allowed easiest into the hospital which treats

the whole family and friendship group of the patient.’ Neville quotes from

WHO Technical Report Series No. 208. 9th Report of the Expert

Committee on Mental Health 1961, p.15 in his paper, ‘Sociotherapeutic

Attitudes to Institutions’ (Yeomans

1965):

‘In the opinion of the Committee, the importance of adequate training in

medical sociology can’t be over estimated, particularly in connection with

the teaching of mental health promotion.’ Neville wrote of that, ‘World

Health Organization Report’ that enlarged upon the growing view that the

recovery of mental patients depends less upon the specific therapeutic

techniques than on the socio-psychological environment of the patients in the

hospital’ (Yeomans

1965 Vol. 12, p. 46, 60-61).

Consistent with creating ‘cultural locality’ Neville went on to say that

Clinicians, ‘must aim at allowing the outside culture into the institution’. The

socio-psychological environment in Fraser House was central to the change

process. As mentioned in the Chapter Three method

section, it took me a long time to realize that the expression, ‘Therapeutic

Community’ was not just a title. Fraser House was a therapeutic community - pervasively. Therapy was the

function; Community was the process.

The word ‘therapy’ was not used in the conventional sense of something

done to someone by a psychotherapist, but in the sense of self-organizing

self and mutual co-reconstituting of wellbeing. The Fraser House milieu was like the soil on the Yeomans’ farm.

It was complex, interwoven and maintained in a thriving state because of very

strategic redesign features that Neville set up and sustained, fully

consistent with thrival aspects within individuals as living system and

between individuals as a Fraser House living system. At Fraser

House, other dysfunctional people were regularly arriving into a community of

dysfunctional people in various stages of shifting towards being able to live

well with others and return functionally to the wider community. It was not

just a unit where everyone did their best to make it therapeutic. In the

Unit, the community as ‘community’ functioned as therapy. In

Fraser House thousands of people were coming and going with between ten and

thirteen thousand outpatient visits annually. There was the therapeutic

perpetual passing on by staff and patient alike of the ‘common stock of

knowledge of how things work around here’ (Berger and Luckmann

1967) - individual quirks,

where things were, who sits in that chair at that time, the little routines -

all the little bits that make living comfortably with others possible. All the

members of the Fraser House therapeutic community – staff, patients and

outpatients - as community, shared their lives with each other. In Fraser

House the norm was created that there was never any blaming of any one.

Anyone blaming himself or herself or anyone else would be immediately

interrupted. If anything happened it was deemed to be a shortcoming of the total community. Neville said that every aspect of Fraser House was

structured as a community system that overrode everything limiting change, even a doctor’s power of veto. Only Neville as director had the power

of veto and he was always driven by

context, and within that, the ecological part of the context; so he too

fitted in with the fitting. Neville’s process is discussed further in Chapter

Five. Any doctor breaking this veto rule would have his or her attention

drawn to it by patients and staff, including the cleaners, and the matter

would be a priority agenda item during the next Big Group. In a 30 June 1999

conversation with Neville he said, ‘Doctors working in Fraser House would

have had their maximal sense of professional powerlessness in their careers.

Doctors being authoritarian was not permitted. Most administrative things

that doctors would decide as a matter of course in other medical contexts had to be brought to meetings where patients had a voice and were in

the majority. If a life-threatening situation occurred where a doctor or

other ‘professional’ felt the need to intervene, then a special committee of

as many patients and staff as possible would be quickly convened. These

temporary special committees would be typically reviewed at the next Big

Group.’ Staff Relating

The nurses and doctors

within mainstream never fraternized in each other’s tea-room; they did

in Fraser House. The mainstream way at the time was that a nurse would always

stand if a Doctor entered a room. Nurses new to Fraser House would be tugged

back down on to their chairs when they stood when a Doctor entered the room.

‘None of that necessary here!’ It took a time for this big change to settle

in. In Fraser House, the shared norm was that ‘the voice of the newest nurse

was just as equal as any one else’. At Fraser House Nurses worked as a team (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4 , p. 17). One of the nurse roles was that of

educator (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4 , p. 20-23). Neville’s

view was that the power – the healing wisdom, psychosocial and emotional

energy, and creativity of the Fraser House community was infinitely greater

than anyone, including himself. According to Neville during an August

1999 conversation, ‘the staff were astonishingly loyal, and acted with

inspired devotion’. Neville gave all concerned almost absolute freedom except

in times of crisis. As a by-product, staff fostered their new profession and

won a new award rate in creating a new role for themselves as nurse

therapists. Fraser House psychiatric nurses were the first ones to achieve a

professional award salary in Australia. Such was the passion and commitment

within the staff that Neville would often have to order them to go home.

Consistent with Neville’s Way discussed in Chapter Three, he would leave

almost total freedom to the community so that it could evolve itself (emergent

and self organizing process). For and Against

While Fraser

House had the support and backing of the Head of the Health Department, the

second string people of the Health Department were bitterly opposed to every

aspect of Fraser House as it challenged every one of their beliefs about

psychiatry, psychiatric nursing, nursing, as well as about hospital

governance, structure, administration and practice. While

operating ‘within’ a ‘government service delivery’ frame, Neville set up

another frame, namely, ‘folk self-organizing self-help action in community’.

Mainstream ‘health’s, ‘we do it for you because we know’ ‘servive delivery’

people had little or no sense of this new form of ancient wellbeing action. The Far-From-Equilibrium Learning Organization

In

complexity terms, every aspect of Fraser House was structured by Neville and

others to maintain the Unit in a far from equilibrium state. Living

systems that are adaptive and thriving well while being provoked and

challenged by the surrounding ecosystem are usually in far from equilibrium

states (Capra 1997, p. 85-94,

102, 110, 175-178, 187). When situations within

Fraser House became stuck, Neville would intentionally provoke it and then

use the evoked heightened emotional contagion as emotional corrective

experience. Some examples of this are given later in this Chapter and later

Chapters. Neville

created a community which was what Senge called thirty three years later a

‘learning organization’ (Senge 1992). The Unit had a culture of

continual review, innovation and openness to try new ways, leading to

sustained negentropy (the opposite of entropy). Neville was decades ahead of

business cultural change practitioners in introducing what has since being

called, ‘a culture of continual improvement’. Many examples of how Neville

sustained this culture are given later. In the business world this culture of

continual improvement is often talked about, but not easily achieved, as conservative

forces constantly subvert the novel in a myriad ways to maintain near

equilibrium conditions. Business leaders are now beginning to realize that

equilibrium in a fast changing world is a dangerous state that impoverishes

an organization’s adaptive capacity (Davis and Meyer 1999; Pascale,

Millemann et al. 2000). The Use Of Slogans

Neville and staff made extensive use of simple slogans to pass

on to newcomers how the place worked. To have staff, patients, and

outpatients embody the values, ideology and practices of the Unit, simple

slogans were restated over and over. For example, the Unit’s social basis of

mental illness perspective was expressed by the slogan, ‘Relatives and

friends cause mental illness’. The idea of potential for change and using

existing internal resources for change was supported by the slogan, ‘No one

is sick all through’. The best advice that could be given a patient was,

‘Bring it up in a Group’. In the early days of Fraser House, permissiveness

within the staff-patient relation was embodied in the slogan, ‘We are all

patients here together’. The self and mutual help focus was supported by the

slogan, ‘We are all co-therapists’. However, recall that boundaries were

maintained between staff and patient, in that any staff needing psychosocial

support would either receive this within an all-staff support group, or if

the situation warranted it, the Staff member would enter Fraser House as a

voluntary patient. Some staff did this. The requirement that patients and

outpatients get on with self and mutual healing and interrupt any mad or bad

behavior in self and others was reinforced with the mantra, ‘No mad or bad

behavior to take place at Fraser House’. Rules/slogans for use by

the staff were mentioned in a document called, ‘How to administrate in Fraser

House’(Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4 , p. 24). Some examples: ‘Know what to leave

undone in an emergency’ ‘Frequent rounds are a

necessity’ ‘Combine the weak with

the strong’ All of the above slogans and rules became a simple shared

language and set of beliefs that were easily taught to new arrivals. I found the same practice of using simple slogans used

informally among prisoners in my prison work in a 63 bed medium security

special protection unit to sustain a smooth running people system. One

example that was repeatedly used by prisoners was, ‘You either do it (time)

easy or you do it hard’, and another was, ‘You do the crime; you do the

time’. These simple notions linked to spontaneous renouncing of the world

outside the prison in many respects made prison life much easier for many

inmates and contributed to their psychosocial surviving. This happened

spontaneously. Socio-Medicine For Social Cohesion - Everyday Life Milieu

Therapy

Within

Fraser House simple and profound changes occurred in people’s lives during,

and as a function of mundane everyday life contexts – as people went about

sharing food, getting dressed, engaging in idle chats and the like. Neville

called this, ‘Everyday Life Milieu Therapy’. For this, Neville drew upon his

understandings and personal experiencing of Indigenous socio-healing way, as

well as from his reading the work of, and conversations with his colleague,

psychiatrist Dr. John Cawte about Australian Aboriginal Sociomedicine (Cawte 1974; Cawte 2001,

(First edition - 1996)). Paul Wilson,

a noted Australian criminologist and a past head of the Australian Institute

of Criminology and current Dean of the School of Humanities at Bond University,

writes of this learning how to ‘live well with each other’ in describing his

experience of living in a therapeutic community Neville modeled on Fraser

House in Mackay some years after leaving Fraser House (Wilson 1990, p.79-80). The Mackay Therapeutic House was far from being a typical

boarding house. Neville told me that he had incorporated and adapted Fraser

House Way to that small Mackay therapeutic community house. Wilson was having

psycho-emotional difficulties in his life at the time and used his stay in

this therapeutic community house to sort out his life. The following quote is

Paul Wilson’s experience of everyday-life milieu therapy: ‘Neville Yeomans

created a community free of doctrinaire principles. The Mackay setting

successfully created a sense of belonging. Most people who have experienced

deep personal distress have lacked, in my opinion, any sense of residing in a

group or clan. They, like I, have lived their lives constructing walls around

themselves, to protect themselves from other people. In the process, they

have lacked the knowledge and experience of living in a community’. ‘There was nothing magical in the process of achieving this sense

of belongingness..... Our day-to-day activities were almost mundane. I would

wake up in the morning and help whoever was up to get breakfast ready. Then as people came in to the kitchen, we would talk about all

sorts of things people talk about over breakfasts. Marion would ask one of us

to collect some groceries, or to cut the lawn, or help with the laundry.’ ‘Most

importantly, there were always people around you who you felt cared for you as

a human being. This interconnectedness of person with person was the thread

that bound the community together and gave us a sense of ‘family’ - a unit

that many of us had ignored or not had before.’ This passage

resonates with the Fraser House milieu, highlighting the point that everyday

life contexts can provide opportunities for one-trial learning about how to

live together. This links to what Neville called, ‘caring and sharing the

Aboriginal way’ – ‘home, street and rural Mediation Therapy’ and the relating

potency of Neville’s ‘mediation

counseling’. Neville had

drawn from his experiences with Aboriginal and Islander nurturers an

extensive array of micro-experiences and simple processes that foster social

cohesion, family friend networking, relationship building, and healing

happening between people in conflict, within a relational mediating healing

frame. As an aspect

of sociomedicine Neville used what he termed, ‘conversational change’. With

this, everyday conversation has potential for reconstituting people’s being

and behavior. In exploring ‘conversational change’ processes, Neville also

evolved a set of micro-experiences that may allow the enabling of healing

action to take place ‘on the run’ as it were, as one goes about relating with

other people in day-to-day contexts. These are resonant with the Milton

Erikson’s therapeutic use of language in everyday life (Bandler, Grinder et al.

1979; Hanlon 1987) and the similar subtle

language Eleanor Porter wrote for her character Pollyanna in the book of the

same name (especially Chapters Eight to Ten) – now available on the internet (Porter 1913). Neville passed these ways on to me in action research contexts.

Neville also used what he called ‘context healing, street mediation and group

story performance’. These draw on Indigenous healing process, cultural action

and cultural healing action (Yeomans and Spencer

1993; Queensland Community Arts Network 2002), corroboree, therapeutic communities, dance movement and

Keyline organic farming concepts and processes. This action uses natural and

evolving contexts as healing possibilities. It also uses what Neville called

mediation therapy and mediation counseling for strengthening healing,

relationship and community. These ways are discussed later. A central

component of Fraser House change was the freeing up of emotional and gut

feelings of all involved while sharing in community as they went about

mundane aspects of everyday life. While drawing on the above ways, Neville

also applied from Taoism the idea that for all at Fraser house, healing came

from ‘letting life act through them’ as they went about their shared life

together in the daily routines of getting up, getting dressed, showering, and

the like. Within Fraser House and the subsequent small therapeutic houses

that Neville established, a change component was this persistent sorting out

of how mad and bad people could live well with each other. Patients,

outpatients and staff became skilled as co-therapists during their respective

stays at Fraser House and would engage in ‘everyday life’ therapy as they

engaged in social interaction with each other. Some adopted Neville’s

conversational change processes by absorbing them into their mode of being,

typically without noticing that they were doing this. ‘Therapy’ wasn’t a

mantle that people put on - it was not a ‘chore’ – it was there as a hardly

noticed aspect of being. Clark and Yeomans’

book contains a segment of a young male patient’s diary (Clark and Yeomans 1969). The earlier section has entries where the

patient writes of his confusion and tentativeness about his life and Fraser

House. His dysfunction is implicit in his writing. As his diary entries

proceed, he records things indicating that he is shifting to functioning well

without giving any indication that he even notices that he is changing. Here

is an excerpt from early in this patient’s personal account: ‘I

am sitting beside Jane in the male group room, holding her bandaged hand. She

is very tense. ‘Please help me’, she says. ‘What is the matter with me?’ ‘I

feel frustrated. I don’t know what to do. I tell her that there must be a

reason for her tension and that she should talk about what bothers her to me

or in the groups. But she says that she never knows what to say.’ He

is out of his depth though he reiterates the Fraser House mantra, ‘Bring it

up in a group.’ A little later: ‘I

catch John on the verandah and when I have told him about what bothers me he

asks me: ‘Have you talked to Jane about it?’ ‘No I have not.’ ‘Why don’t

you?’ he says then. ‘She has been leaning on you for so long now, why not

turn the tables for a change and let her help you?’ I haven’t thought of it,

but it sounds logical enough.’ This

is an example of self-help through mutual-help. While these exchanges seem

trivial, Neville and the other interviewees said that time and again the

Fraser House experience was that trivial exchange was potent. At the

end of this patient’s diary he has been assessed as ready to leave Fraser

House and return to the wider world. Nowhere does he give any

indication that he has any insight into the process whereby change to

wellbeing and functional living is occurring in his life, or that such change

is even occurring. He was not engaging in any intellectual sabotage of his

changework – behaviors like faultfinding, judging, blaming, and condemning. Fraser House Social Ecology

The

total Fraser House process curtailed any physical violence. Any newcomers

were assigned a buddy for sometime who tagged them so they were never alone. A ‘contract’ was made that

everyone at Fraser House, staff, patients and outpatients alike, were to

watch out for violent situations and to restrain and interrupt people,

preferably before problematic situations even got under way. No informant had

any knowledge of any staff member ever been seriously hurt. Fraser House was

a relatively big place - around 250 meters long. Outside of Big and Small

Groups and the intervening tea break, people were always spread throughout

the buildings or on the move. Some fights did break out between patients and

were typically interrupted quickly. Any unusual noise would immediately

attract a crowd. The energy and ethos of the Unit was always to respond

immediately to disturbance and interrupt, rather than to encourage fighting,

as more typically happens in wider society. Typically, if something happened

say, late at night, any patient or staff member spotting it would immediately

get everyone who was up and about to form a group (often a fair size group -

as many as they could get) to go to the ‘disturbance’. If someone was doing

an ego trip, he or she would be ‘dumped on big time’. Other

mitigating factors were the continual presence of an audience, the presence

of females and children, and knowing that violence, or threats of violence

would be brought up in Big Group with around 180 mad and bad people present

to focus on the perpetrator(s) of violence. Violence and other unacceptable

behavior would also be invariably discussed in small groups. Typically, there

was commitment to healing in patients and outpatients. All knew that the very

strong expectation within the Unit’s milieu was that, ‘here people change and

return to the wider society well’. There was also a continually reinforced

mantra, ‘no mad or bad behavior to take place at Fraser House’. Crazy

behavior was expected and accepted at every other mental hospital in Australia – after all, the

reasoning went, ‘Patient are crazy,

so what else would you expect’. In stark contrast, new arrivals would have a

settling in period where their mad and bad behavior would be pointed out to

them. Increasingly, mad and bad behavior would be interrupted in ways

discussed later. Patients

also knew that violence could mean their treatment could be terminated.

Recall that another pressure to change was a time limit on a stay at Fraser

House of six months. Recall that during 1965 the common limit rule for staying at the Unit was

five months This was later tightened to three

months and the average length of stay was six weeks (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4 p. 2-4). After

leaving, people could return two more times by arrangement. These limits

reinforced the, ‘you will return to the wider community’ framing that was

pervasive at Fraser House. After leaving Fraser House people could stay in

‘contact’ with the Fraser House milieu because they had this sustained in

their reconstructed family-friend network Handbooks On Fraser House Structure And Process

Neville gave patients and

outpatients the task of becoming so familiar with Fraser House structures and

processes including the processes Neville and others used to enabling Big and

Small groups that they could and did write extremely well written and

succinct handbooks for use by new staff, patients, outpatients and guests (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 4). Neville wrote the

introduction section of a Handbook called, ‘Fraser House Therapeutic

Community’. This was one of a number prepared at different times specifying

the Unit’s structure-process. Two other statements about Fraser House

structure and process was the February 1965, ‘Introducing a Therapeutic

Community for New Members by the Staff of Fraser House (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4).

A 1966 draft of the Second Edition of the above document was a

complementary document to the document, ‘Staff Patient Organization in Fraser

House and was largely written by patients (Yeomans

1965, Vol. 4). In March 2003 Chilmade

wrote to me saying that there were handbooks (roneoed typed sheets) both for

patients and relatives. The staff handbook was for longer term staff. ‘I didn`t

get one in my first stay of 3 months in 1962, but did get one (borrowed &

not returned) in 1966 when I spent a full year there. Patients did not get

access to the staff handbook.’ SELF-GOVERNANCE

AND OTHER RECONSTITUTING PROCESSES

The Resocializing Program – Using Governance Therapy

Neville

set up a process whereby patients evolved response abilities by taking responsibility

for their own democratic self-government. Neville

referred to patient-based rule making as creating ‘a community system of law’

(Yeomans 1965, Vol. 3). Law evolved out of evolving Fraser House lore. The Fraser House

vehicle for evolving democratic self-governance initially was a committee

that decided the ground rules for ward life called appropriately the Ward

Committee. Eventually

many committees were established. Patients

outnumbered staff on all committees. Each committee member had one vote. This

meant that patients could always

out-vote staff. This often happened. Neville set the committee ground rules

such that he always had a power of veto. Dissenting people who felt strongly

enough about a decision could take it before Neville and the decision would

be held over till he attended the particular committee where people would

present their views. Neville

rarely overturned a decision made by patients where staff dissented, as by

Neville’s reckoning after due consideration, the patients generally held the

better stance. In his

paper, ‘Sociotherapeutic Attitudes to Institutions’ and consistent with

creating ‘cultural locality’ Neville wrote, ‘Patient committees formalize the

social structure of the patients’ sub-community (Yeomans 1965 Vol. 12, p. 46, 60-61). Neville being ‘dictator’ satisfied

the Health Department’s requirements for Top-Down control. However, in

practice, Neville was a benevolent dictator’ and the patients and outpatients

effectively ran the place – and by all accounts, they ran it effectively. Chapter

Ten discusses Neville’s using his patient self governance processes as a

model for post war reconstruction of decimated societies. The Ward Committee

Patients

were voted on to the Ward committee by their peers and readily participated.

This first of many committees decided matters such as when lights went on and

off, and patient conduct within the wards. The Ward Committee evolved to be

the main process for evolving the Unit’s rules and disciplinary process in

ensuring compliance with the rules. The

Ward Committee membership was typically isomorphic with the ward’s mix

relating to the merging of opposites. Typically, diabolically autocratic

people served along side people who displayed extreme tolerance and

passivity. Criminals often with a tough ‘no mercy’ attitude would serve with

the anxious over-controlled. This was another social context for working out

how to work together, and working this through created potential for all

involved to catch glimpses of a metaphoric normal person somewhere in the

middle. And then, ‘Yeh! I can do that!’ ‘We can work this out!’ Patient Administration

The other

early committee was a Parliamentary Committee that grew to be a committee

that governed the work of all other committees. Every member in every other

committee was automatically a member of the Parliamentary Committee. The

Pilot Committee was a ‘Committee of Review’ of the Parliament Committee.

Within a very short time, a number of patient-run

committees and work groups were set up that involved the patients themselves being

actively involved in making decisions and taking actions on every

aspect that normally would be the role of Fraser House administration people.

Neville evolved the Fraser House committee process

so that eventually the committees involved the Committees taking on aspects of all of the roles normally undertaken by staff. Imagine

psychiatric patients returning to everyday life with finely honed practical

skills in administering a complex organization having for example, over

13,000 outpatient visits a year. This is what happened. When they were back

in their community and learning to interact with people at say, the counter

in their local Child Endowment office, the patients typically had some

understanding about how bureaucracies worked through personal experience. The

structures and process of the committees were being continually fine-tuned.

Chapters 8 and 9 of Clark and Yeomans book (Clark and Yeomans 1969) contain a detailed description

of the patient committees at one point in time. Figure 04 below shows a

diagram from Clark and Yeoman’s book depicting Patient Committees and the staff

devolving their traditional roles to become healers.

Diagram 2 Patient

committees and the staff devolving their traditional roles to become healers (Clark and

Yeomans 1969) The

respective roles that were devolved to the committees were, psychiatrist,

charge nurse, nurse, occupational therapist, social worker, and

administrator; these are depicted by the darker boxes. The various committees

that took on aspects of the foregoing roles are shown in the lighter boxes. All of the above committees were isomorphic with mainstream

administrative cleaving; even following the Federal Government’s

Parliamentary Review Committee (the Fraser House Pilot Committee) and using

the term ‘Parliamentary’ Committee’. This reframed matching by Neville of

mainstream structures and processes was a precursor of Neville’s 1999

Extegrity Program documentation specifying frameworks for bottom-up

grassroots self-organizing mutual-help towards reconstituting decimated

societies. This is discussed in Chapter Nine. Another

snapshot of the committee structure and process is in the Fraser House Staff

Handbook (Yeomans 1965). A further view is in Dr. N. M.

Mitchell’s monograph on the Committee Structure at Kenmore Hospital

Therapeutic Community in Goulburn (Mitchell 1964) held at the Kenmore Hospital Museum. Kenmore’s Therapeutic Community was modeled

on Fraser House. This is discussed in Chapter Seven. The New

Role For All Staff

In

this devolving, staff took on the enabling/mentoring roles in respect of the

patients taking over the staff’s administrative duties. This freed up all the

staff including the cleaners to be also supporters of self-healing and

mutual-healing by the patients and outpatients. The patients did the

cleaning, with cleaners in mentoring roles. Because the cleaners were

constantly present in the community during day work hours, they saw most of

what was going on. Aided by this, and by common agreement of patients and

staff, the cleaners were the most insightful community therapists after

the patients. This skilled therapeutic role of the patients and cleaning

staff was reported in the research, writing, and archives, and collaborated

by interviewees. Recall all staff attended Big Group – including the cleaners.

Some cleaners became very insightful therapists - the ‘onlooker seeing most

of the game’. On one occasion, mentioned by Neville in a conversation we had

in Yungaburra Queensland during December 1992, a cleaner spotted that a

catatonic women had drawn a beautiful horse in a moment of lucidity. The

cleaner mentioned about the catatonic’s drawing skills during a Big Group and

suggested that a drawing pad and colored pencil-set be left beside her so

that she may be prompted to stay lucid longer. This was done and the

catatonic patient did start to draw. To encourage her further, a full

painting kit was arranged to be place beside her. After a time a set of

poster colors in pots were set up and a nearby wall was designated as the

‘mural space’ and mentioned her name. In the end this patient came out of her

catatonia and painted beautiful big murals over a section of the Unit and

largely from this work. At one stage she was running out of walls to paint

and this coincided with word being received on the grapevine that a’ razor

gang’ would arrive that might recommend closing the Unit if it was deemed to

‘way out’. After discussion in Big Group about this impending inspection it

was agreed that everyone would help in painting over the murals and returning

the unit to white. When the inspectors arrived the staff where in their white

uniforms in a white unit. The inspectors saw little that was out of the

ordinary and okayed the Unit. After they left the mural painting resumed and

after a time this person was able to return to living in society. All

of the staff were entering into new territory at Fraser House. No one, including

Neville, had any prior experience

of facilitating the collective action therapy of patient self-governance, or