Chapter Two - Neville’s Model for a 250-Year

Transition to a Humane Caring Epoch

INTRODUCTION

During the years 1993

through to 1998 (when I started this thesis), my understanding was that the

main reason Neville was evolving networks from the early 1970’s in Far North

Queensland and the Darwin Top End in Australia was to keep these networks away

from dominant interests who may seek to undermine and subvert the social action

he and others were engaged in.

In October 1998 I found

Neville’s paper, ‘Mental Health and Social Change’ (Yeomans, N. 1971a; Yeomans, N. 1971c) in his Mitchell Library archives. It is a

scribbled half page note and a hand sketched diagram written back in 1971. It

discusses the nature of transitions to a new epoch. It revealed that Neville

had specifically chosen Far North Queensland because of his analysis of its

strategic locality on the globe as a place to start towards a global

transition. Still, I did not take this seriously and immediately turned the

page to the next item. I sensed that it was more to do with being ‘away from

mainstream’. I did not realize at the time that this was a crucial document

briefly specifying Neville’s core epochal framework. In this ‘Mental Health and

Social Change’ file-note Neville clearly specifies epochal transitions. (I even

missed the significance and evocativeness of the title ‘Mental Health and

Social Change’. What for Neville was the link between ‘mental health’ and

‘social change’?) This is an example of how my pre-judging mind limited my sensing.

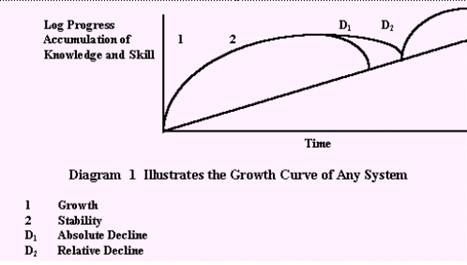

Neville wrote (Yeomans, N. 1971a; Yeomans, N. 1971c) the following on epochal change in that file

note:

The take off point for the next cultural

synthesis, (ed. point D in Diagram 1 below) typically occurs in a marginal

culture. Such a culture suffers dedifferentiation of its loyalty and value

system to the previous civilization. It develops a relatively anarchical value

orientation system. Its social institutions dedifferentiate and power slips

away from them. This power moves into lower level, newer, smaller and more

radical systems within the society. Uncertainty increases and with it rumour.

Also an epidemic of experimental organizations develop. Many die away but those

most functionally attuned to future trends survive and grow.

Diagram

1. Neville’s Diagram of the Growth

Curve of any System

In saying, ‘Its social institutions

dedifferentiate…’ Neville is talking about a shift away from dynamic

differentiated adaptive far-from-equilibrium states to non-adaptive

sameness. With the words, ‘those most functionally attuned to future trends

survive and grow’, Neville was hinting at his own aspirations.

In the same document (1971a,

1971c) Neville went on to talk about the strategic significance firstly, of

BUT - it is also the only

continent not at war with itself. It is one of the most affluent nations on

earth. Situated at the junction of the great civilizations of East and West it

can borrow the best of both. Of all nations it has the least to lose and most

to gain by creating a new synthesis.

Given all of the aspects

outlined above, for Neville, the

In December 1993, Neville

told me to remind him to get me a paper that he had written back in 1974

called, ‘On Global Reform – International Normative Model Areas’. Neville later

told me he could not locate the document. It was not until July 2000 (two

months after Neville’s death) that I found this ‘On Global Reform’ paper (Yeomans 1974). This is one of, if not the most significant

of the papers Neville wrote. Once I read it I suddenly knew of the strategic

significance (way beyond just minimizing interference from mainstream) of the,

‘Mental Health and Social Change’ paper mentioned above (the one that I had

spotted in the archives in October 1998). On Global Reform is discussed in

Chapter Thirteen.

The thesis will detail how

the essence of INMA (International Normative Model Area) specified in Neville’s

poem[1]

of the same name(Yeomans 2000a) was woven into Fraser House and into the

many Fraser House outreaches leading up to the evolving of the Laceweb social

movement. Chapter Twelve and Thirteen describe how Neville’s creation of an

INMA in the Atherton Tablelands and another in the Darwin Top End were

fundamental in evolving the Laceweb.

A

NEW CULTURAL SYNTHESIS

Neville’s view (Dec, 1993;

July, 1998, Oct, 1998) was that culture was ‘how we live together’. Science,

technology, economics and politics all take place in the context of how we live

together in our places. Neville set out to action research fostering new local,

regional and global ways of living, playing and sharing our artistry together

(cultures and inter-cultures) towards new cultures, new cultural syntheses and

a new global intercultural synthesis. The processes he explored were guided by

humane caring respecting values, and his action research involving

dysfunctional people on the margins embodied these values. Neville’s view (Dec,

1993; July, 1998, Oct, 1998) was that new directions and uses of science,

technology, economics and politics would evolve, guided by these values enacted

in everyday life together. This is explored further in Chapters Twelve and

Thirteen. The next segment introduces the Laceweb.

WEBS AND LACEWEBS

One summer morning in December 1993 in Yungaburra in Far

North Queensland, Neville and I were discussing the networking he was linked

into, and it seemed that the movement had, as far as Neville knew, no name.

Neville knew the potency of symbols, icons and logos and said these were not

used in the movement, and he did not think them in any way appropriate at the

present. Neville talked about naming the movement. Within seconds he came up

with ‘Laceweb’. This name was, in Neville’s terms, ‘an isomorphic metaphor’ –

something of similar form and resonance to the social movement that was

evolving.

The name was from a natural outback Australian phenomenon

that Neville had personally experienced. Some years previously Neville had been

travelling alone in outback

Neville’s

dreaming was of an entirely new form of social movement - an informal Laceweb

of healers from among the most downtrodden and most disadvantaged marginal

people of the world. What follows is from my file note about how Neville

described the desert web and the Laceweb as being of similar form (December,

1993):

‘The

Laceweb is the manifestation of a massive local co-operative endeavour. Not

carved in stone, rather – it is soft, light, and pliably fitting the locale and

made by locals to suit their needs. Like the spider web, the Laceweb would

appear out of nowhere. When you discover it, it would already have surrounded

you. It is exquisitely beautiful and lovely. When you have eyes that see it,

the play of reflectant light upon it in the morning sunlight is extra-ordinary.

It attracts and stores the dew in little beads. Like the desert web, the

Laceweb extends way beyond the horizon. It is suspended in space with links to

shifting things - no solid foundations here. It has no centre and no part is

‘in charge’, and in that sense, no aspect is higher or lower than any other. It

is not what it first seems. It is at the same time riddled with holes, whole

and holy. It is merged within the surrounding ecosystem and lays low. In one

sense it is delicate - in another it is resilient. Bits may be easily damaged.

However, to remove it all would be well nigh impossible. It is formed through

covalent bonding between its formers and within its form. It is an attractant.

Local action may repair local damage. It is very functional. It is what the locals

need. And it does help sustain them.’

Neville

and I explored the derivation of ‘vale’, ‘valence’, and ‘valency’ - from the

Latin imperative – to be well, to be strong. ‘Co-valence’ is to be bonded

together in mutual attraction. After the foregoing spontaneously poetic

expression, Neville told me (December, 1993) that the desert web was the

perfect metaphor for his movement.

SUMMARY

This Chapter has introduced the topic and the

history, theory and practice leading to the evolving of a social movement known

as the Laceweb. The next chapter reviews the literature on therapeutic

communities.