Chapter

Three – The Emergence of Therapeutic

Communities and Community Mental Health – History, Types and Significance

OVERVIEW

This chapter provides a background to my research into

Neville’s pioneering of therapeutic communities and community mental health in

THE EMERGENCE OF POPULAR/FOLK AND

SCIENTIFIC MODELS

Throughout human history there have been

popular/folk models about mental malfunction based upon culturally derived

belief systems (Engel 1977). Prior to the Twentieth Century, in the

United Kingdom, the United States of America and other places, individuals with

mental malfunctioning experienced harsh inhumane treatment (Roberts 2005a; Roberts 2005b).

Physical and mental abuse was commonplace. There was wide use of

straight jackets and heavy arm and leg iron bands and chains (Roberts 2005a; Roberts 2005b). Kennard writes of what was called as early

as 1796 ‘moral therapy’ as an early precursor to notions of therapeutic

community (2004, p. 298):

The application of therapeutic community principles to work with the chronic mentally

ill is, in many ways, the closest version of therapeutic community modality to one of its most important predecessors,

Moral Treatment. This was the term used to describe a model of care first

developed in 1796 by the Quaker William Tuke at The Retreat in York (Tuke 1813; Borthwick A., Holman C. et al. 2001).

In keeping with Quaker ideology, the mentally

ill were accorded the status of equal human beings to be treated with gentleness,

humanity and respect. This was quite revolutionary at the time, and The Retreat

also gave priority to the value of personal relationships as a healing

influence, to the importance of useful occupation, and to the quality of the

physical environment. Much of this early vision of a humane treatment for

mental illness was lost as the 19th century progressed and the mentally ill

were housed in increasingly large and impersonal asylums (Kennard 2004, p. 298).

In

What he observed was a strict non-violent,

non-medical management of mental patients came to be called ‘moral treatment’

though ‘psychological’ might be a more accurate translation of the French

‘moral’ (2005).

Notwithstanding the ‘humaneness’ of the approach, Pinel

condoned the use of threats and chains when other means failed (Dr. Grohol's Psych Central 2005).

Moral treatment was also

used by Sir William and Lady Ellis in the

1900s (History of

Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 2005) who came

to be in charge of England's county asylums. Under the Ellis’, asylums as ‘community’ had a family atmosphere and the

men and women were encouraged to enhance their previous trades or establish new

ones in order to support purposeful activity. Sir and Lady Ellis were able to

prove that the mentally ill were not dangerous with tools, and were far less

dangerous than other unoccupied individuals. The Ellis' were also responsible

for developing the idea of an ‘after care’ house, very similar to the halfway houses

of today. These places functioned as stepping-stones from total care to limited

assistance living care.

The Religious Society of Friends founded

The York Retreat and the

In the later 19th and the early 20th

centuries psychiatry was in the process of seeking links with academic

disciplines. Medicine was doing the same thing (Engel 1977; Bloom 2005). While medicine had been evolving within

biological frameworks, Rudoph Virchow writing in 1848 wrote that ‘Medicine is a

social science’ (Rosen 1974).

Bloom identifies the rise

of biopsychosocial

approaches in psychiatry in the 1920’s and traces the professional links made

by psychiatrists to evolve their specialty in the 1920s.

Bloom (2005, p.77) states:

Collaboration between

sociology and psychiatry is traced to the 1920s when, stimulated by Harry Stack

Sullivan and Adolph Meyer, the relationship was activated by common theoretical

and research interests. Immediately after World War II, this became a true

partnership, stimulated by the National Institute of Mental Health, the Group

for the Advancement of Psychiatry, and the growing influence of psychoanalytic

theory.

Bloom continues (2005, p.

81):

One piece of evidence of

this development was the emergence of the new subspecialty of social

psychiatry. Initiated in

Colloquiums were held in 1928 and 1929 under the auspices of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Relations with the Social Sciences. As well as psychiatrists, the colloquium attendees were psychologists, political scientists, anthropologists and sociologists. These two colloquiums helped forged psychiatry’s links with the social sciences.

In the context of this reaching out to the

social sciences and as an indication of the acceptance of psychiatry by the

medical profession in the 1920’s the APA chairperson White stated during the

1929 Colloquium:

The specialty of psychiatry is almost universally

neglected by medical education (White 1929, p. 136).

Bloom (2005, p81.) quotes

Grob (1991) writing that it was,

…..the triumph of the

psychodynamic approach….that set the stage for the collaboration and

cross-fertilization of psychiatry with the behavioural and social sciences in

the 1950s.

The effects of a sociology that focused on issues of health and illness proceeded to grow in medical education, research, and the treatment of mental illness until 1980, when a distinct shift of emphasis in psychiatry occurred.

After the rise of biopsychosocial

approaches in the 1920’s there was a move away from the biopsychosocial to a

biopharmacological model in the 1980’s (Bloom

2005, p. 77):

In its role as educator of

future physicians, post-war psychiatry developed a paradigm of biopsychosocial

behaviour but, after three decades, changed to a biopharmacological model.

The definition of mental

illness as a deviant extreme in developmental and interpersonal characteristics

lost favour to nosological diagnoses of discrete or dichotomous models. Under a

variety of intellectual, socio-economic, and political pressures, psychiatry

reduced its interest in and relationship with sociology, replacing it in part

with bioethics and economics (2005, p. 77).

Speaking of the 1950-1970 period Bloom (2005, p. 82)

discusses important changes in psychiatric approach and educational method:

…the focus was on human behaviour, and the theoretic

model was psychodynamic. George Engel, in what he called the biopsychosocial

model, gave voice to this point of view more than any other single voice.

Engel and others argued for both medicine and psychiatry

to be modelled on the biopsychosocial:

To provide a basis for understanding the determinates of

disease and arriving at rational treatments and patterns of health care, a

medical model must also take into account the patient, the social context in

which he lives, and the complementary system devised by society to deal with

the disruptive effects of illness, that is the physician role and the health

care system’s. This requires a biopsychosocial model’ (1977, p. 32).

Bloom refers to Mechanic (1999) writing of the biopsychosocial being based

on a continuum and the biopharmacological being based on discrete or

dichotomous model. Mechanic describes

two definitions of mental health:

One presented a continuous model of mental health and

illness, the other a discrete or dichotomous model of mental illness. In the

first, mental health and illness are the opposite ends of a continuum; the

second rejects such a continuum, instead fitting a medical model of specific

disease categories with measurable symptoms (Bloom, 1997, p. 78).

Engel makes the point that:

Other factors may combine to sustain patienthood even in the

face of biochemical recovery. Conspicuously responsible for such discrepancies

between correction of biological abnormalities and treatment outcomes are

psychological and social variables (1977, p.132).

In the Seventies the debate about appropriate models for

both psychiatry and medicine continued. Some argued the medical model is not

relevant to the behavioural and psychological domains.

Disorders directly ascribable to brain disorder would be

taken care of by neurologists, while psychiatry as such would disappear as a

profession (Engel, 1977, p.129).

In the late 1970’s one view

of psychiatry documented by Engel was:

Psychiatry has become a

hodgepodge of unscientific opinions, assorted philosophies and schools of

thought, mixed metaphors, role diffusion, propaganda, and politicking for

‘mental health’ and other esoteric goals (Engel 1977, p. 129).

Today psychiatry has typically maintained a biopharmacological model as a biomedical sub-specialty (Bloom, 2005).

The next section explores what was actually happening to

people suffering mental malfunction since the late 1800s.

NINETEEN AND TWENTIETH CENTURY

PRACTICE

USA

In the Nineteenth Century, the

The publication by Clifford Beers of his expose of his

USA experience in the state asylum system, ‘A Mind That Found Itself’ (1908) had a wide and immediate impact both in

America and overseas towards reforming and humanizing mental health practices.

In the same year Beers founded the Connecticut Society for Mental Hygiene, and

the following year founded the

National Committee for Mental

Hygiene. This entity merged with others in the

Early Australian Experience

The Central Sydney Area

Mental Health Service’s (2004) ‘History

of Rozelle Hospital (formerly Callan Park)’ reports that:

Social deviants were often

treated brutally and alcoholism was rife in the new colony. Governor Bourke in

1820 wrote that ‘a lunatic asylum is an establishment that can no longer be

dispensed with.

The

Australian experience followed that of the

Psychiatry

in

·

1788 to

1839 - The Primitive Era. (The Beginnings)

·

1839 to 1860

- The Moral Treatment Era. (The Romantic)

·

1860 to

1945 - The Physical Treatment Era. (The Classical)

·

1945 to

the present day - The Modern Era. (The Revolution in Therapy)

On 1 July, 1876, Manning was appointed by the Colonial Government as the

Inspector of the Insane for mental institutions in NSW (The Central Sydney Area Mental Health Service 2004). Manning was noted for his humanitarianism. His

constant desire was to ensure that his patients received treatment for their

illnesses rather than confinement in a ‘cemetery for deceased intellects’.

Despite overcrowding with 1,078 patients being recorded in 1890, the

Hospital (Callan Park) at the turn of the century was considered to be one of

the ‘finest Institutions in the Commonwealth for the housing and treatment of

persons, suffering from mental disorders’ (Leong 1985).

Photo 1.

Photo of Callan Park (Leong 1985)

Two World Wars and the Great Depression brought social upheaval and

hardship and further overcrowding. Demands for financial austerity eventually

lead to

Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital

in Campbelltown which opened in January 1895 following a building

program which started in 1893 and expanded to have over 1,800 patients (Mitchell 1964).

Other large asylums were

also built in

There is no doubt in my mind that the

patients are kindly treated, and that any attempts to ill-use them would, if

they came to the knowledge of the superior officers, be most vigorously dealt

with.

Asylums in

UK

Throughout the Nineteenth

Century many madhouses and asylums were built and regulated under various Acts

of Parliament (Mind 2005). For

example, the 1828 Madhouses Act, regulated conditions in asylums including the

moral conditions. Official visitors were required to inquire about the

performance of divine service and its effects. In 1832 this Inquiry was

extended to include ‘what description of employment, amusement or recreation

(if any) is provided’.

The last of the (large)

mental hospitals to be built in England and Wales was in the early 1930’s (Roberts

2005a; Roberts 2005b).

EVOLVING THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITIES

This section discusses the

rise of therapeutic communities, the ways in which therapeutic communities

differ from asylums and the psychosocial healing potential of communal living.

Kennard refers to the link

between community and healing:

The idea of a community as a

place of healing for the troubled mind is probably universal and as old as

society itself. One of the earliest recorded intentional uses of a community in

this way was Geel in

Kennard identifies the

founding of the Little Commonwealth by

Lane was an American who had

experience as an educator at the George Junior Republic, a reformatory system

developed in the United States, and was invited to advise on the setting up of

a home for delinquent adolescents in Dorset in south west England. For 5 years

the Little Commonwealth housed around 50 youngsters, mostly aged 14–19, who

participated in a carefully structured system of shared responsibility. Lane

wrote that the chief point of

difference between the Commonwealth and other reformatories and schools is that

in the Commonwealth there are no rules and regulations except those made by the

boys and girls themselves. All those who are fourteen years of age and over are

citizens, having joint responsibility for the regulation of their lives by the

laws and judicial machinery organized and developed by themselves (Kennard 2004, p. 296).

This is an early example of the interconnected

psychosocial process of marginalized people on the fringe of society

co-constituting themselves in the process of establishing and maintaining their

lore, norms, law, self governance and shared community.

A biopsychosocial approach

addressing general health was the 1935 ‘Peckham Experiment’

at the Pioneer Health Centre in

According

to the Southwark Council Website (2005) this centre was:

…a

unique attempt to raise public health through a combination of education,

community care and preventative medicine.

The

experiment came about in response to worryingly low levels of health and

fitness amongst low-income inner-city families. Doctors Scott Williamson and

Innes Pearse (a husband and wife team) believed that social and physical

environment could have a direct affect on health - and looked to prove it.

Just

as we now join gyms, 950 families signed-up, paying one shilling a week to

relax in a club-like atmosphere where physical exercise, games, workshops and

relaxation were all encouraged. The families were constantly observed by

Williamson and Pearse's team of doctors - and attended thorough medical

examinations once a year.

The

experiment was a bold departure in the medical field in the 1930s,

concentrating on a preventative, rather than a curative approach to health -

and its setting was equally pioneering. The well-lit and open-plan design of

the building (designed by Sir Owen Williams) was far ahead of its time, providing

an ideal environment for observation and relaxation.

One

historical record describes the

large Pioneer Health Centre’s as having:

…. an out door area for roller-skating, cycling and

sports. Inside the building, you notice that large windows allow you to see the

activities of the gym, swimming pool, games area, nurseries, dance floor,

cafeteria, theatre, library and workrooms from almost any point in the

building. The facility is fully equipped with a modern laboratory and medical

staff. Many areas are designed with rollaway rooftops to allow fresh air, and

sunshine when available. The centre is designed to accommodate leisure

activities of 2,000 families (Chek 2005).

Membership of the

centre entitled all members of the family to participate in a wide range of

sports, pastimes, crafts, social and learning activities as well as community

dining.

Photo

2.

The Purpose Built Peckham Centre

- (Peckham

Health Centre 2005)

The

centre research showed significant improvement on a range of medical and

wellbeing indices compared with baseline entry levels.

The

experiment continued until 1950, concluding that: ‘It is not wages that are

lacking ... but quite simply ... social opportunities for knowledge and for

action that should be the birthright of all; space for spontaneous exercise of

young bodies, a local forum for sociability of young families, and current

opportunity for picking up knowledge as the family goes along’ (Chek 2005).

Peckham is an early example

of social learning in transitional community.

Kennard (2004, p. 304) refers to the 1939-1945 period in England

and the development of therapeutic community:

What seemed to happen at this moment in

history was that a particular constellation of human ideology, wartime

necessity, psychoanalytic insights and open mineded pragmatism came together

and coalesced into a new form of treatment.

Kennard (2004, p. 299) writes that following World War Two the zeitgeist for the mentally ill began to

change:

‘Factors which can be seen to have

contributed to this included the founding of the English National Health

Service, the emergence of sociological studies of the toxic nature of large

institutions, and the (re)discovery of a humane and egalitarian model of care

in the shape of the therapeutic community experiments during and following the

Second World War.

Bloom (2005 p.80) refers to the link between personality

and society:

The core of both social and psychiatric

theoretical speculation stimulated by the war was that the social structure and

personality are linked. Differing in its particulars but similar conceptually

was the interpretation of the hospital as a therapeutic community.

UK

The Second World War created a context that contributed

to major change in the treatment of the mentally ill. By the end of the Second

World War both

There, a group of psychoanalysts and group

therapists working with demoralized psychoneurotic ex-soldiers developed a new

pattern of institutional life (Clark, 1974, p. 29).

Weisaeth and Eitinger (1991) make the point that:

Although it is well known that the principles of forward

psychiatry were rediscovered in WWII, not everyone is aware that modern

treatment principles such as the therapeutic community and group therapy were

also developed by psychoanalysts in the British Army. The late Tom Main's ‘The

Ailment and Other Psychoanalytic Essays’ (1989) provides important information about this.

The conventional asylum of the day replicated most of the

rigid life-controlling daily routines of the returning soldiers’ former

prisoner-of-war camps. Main’s aim was to re-socialize the hospital’s patients

via ‘full participation of all its members in its daily life’.

The Northfield Experiment is an attempt to

use a hospital not as an organization run by doctors in the interests of their

own technical efficiency, but as a community with the immediate aim of full

participation of all its members in its daily life and the eventual aim of

re-socialisation of the neurotic individual for life in ordinary society (Clark 1974, p. 29; Main 1989).

Some psychiatrists caring for these ex-soldiers

recognised that major changes to ‘treatment’ had to occur for these people to ever

be able to return to functional living in society. Psychiatrists began

exploring community-based approaches to reconnect these former soldiers with

society. Given the community approaches being used, these units became known as

therapeutic communities.

Maxwell Jones is recognized as the main developer of

therapeutic community (Jones 1953; Jones 1957). In contrast to the conventional

asylums, Jones writes of starting at

By great good fortune I was asked to organize

a treatment unit for British ex-prisoners of war who had just returned from the

prison camps in

And so, almost imperceptibly we moved from

the idea of teaching with a passive, captive audience, to one of social

learning as a process of interaction between staff and patients. By the end of

the war we were convinced that people living together in hospital, whether

patients or staff, derived great benefit from examining, in daily community

meetings, what they were doing and why they were doing it (Jones 1968, p. 16-17).

Kennard writes of wide interest in Jones’ work (2004, p. 299):

Right from its early days

Maxwell Jones’ experiment at

In stark contrast to conventional asylum top-down

autocratic structure, Maxwell Jones writes of re-constituting towards democratic

egalitarian structure/processes having three main objectives – communication,

decision-making and culture:

…the establishment of two-way communication

involving as far as possible all personnel, both patients and staff; decision

making machinery at all levels, so that everyone has the feeling that he is

identified with the aims of the hospital, with change, and with its success and

failures; the development of a therapeutic culture reflecting the attitudes and

beliefs of patients and staff and highlighting the importance of roles and role

relationships (Jones 1968, p. Xlll).

These changes in communicating, decision-making and

culture were core shifts in changing from top-down expert driven hierarchy to a

democratic egalitarian holarchy (each participant as networked part of the

whole) with a community focused structure:

In a therapeutic community communications at

all levels are made as efficient as possible, and decision-making by consensus

is aimed at.

In a therapeutic community, a unilateral

decision, no matter how wise, is seen as contradictory to the basic philosophy (Jones 1969, p. 48).

In this shift to a flatter structure, Jones suggests that

a more apt name for the leader is ‘catalyst or charismatic leader’ (Jones 1969, p. 24).

Two-way communication and all-inclusive meetings change

the notion of ‘confidentiality’. Information is to be kept confidential within

the community, not just within the patient-psychiatrist relationship (Jones 1969, p. 54).

In his book ‘Administrative Therapy’, D, H. Clark (1964) writes of using meetings and other aspects

of administration as an integral aspect of patient change, what he called

‘Administrative Therapy’.

Maxwell Jones expands on these re-socializing themes:

The psychiatric hospital can be seen as a

microcosm of society outside, and its social structure and culture can be

changed with relative ease, compared to the outside. For this reason

‘therapeutic communities’ to date have been largely confined to psychiatric

institutions. They represent a useful pilot run preliminary to the much more

difficult task of trying to establish a therapeutic community for psychiatric

purposes in society at large (Jones 1968, p. 86).

In a conversation I had with

Alfred Clark (June 2004) he recalled the term ‘civil

reconnection’ for what the

Jones saw therapeutic community as an adjunct to existing

processes:

It does not amount to a treatment methodology

in its own right but complements other recognized psychotherapeutic and

pharma-cological treatment procedures (1969, p. 86).

Jones and others recognized potential in hospital social

restructuring:

A hospital has the advantage of being a small

community where it is possible to organize the social structure so that it

enhances social learning (1969, p.91).

Jones called this setting up a ‘living-learning’

situation:

The term is meant to convey the concept of

social learning as it applies to the problems of everyday living (1969, p. 87; Kennard 2004).

Jones adds that along with structure - roles, role

relationships and culture may be involved in re-socialising:

The concept of the therapeutic community

stresses the importance of social structure; it underlines the need to focus on

roles and role relationships and to evolve a therapeutic culture (1969, p. 86).

David Clark, in writing the history of

…mixed-sex wards, no staff uniforms, ward

meetings, staff discussion groups and open and free discussion between

professions. There was plenty of encouragement for patients to help each other

and to talk openly with staff, as well as active involvement of, and discussion

with relatives of patients (1996).

Other aspects were:

Doctors’ Sensitivity Meeting on Fridays (with

its egalitarian sharing), the Hospital Innovation Project, and the culture of

growth.

Basic premises of the therapeutic community

are the abolition of hierarchy and authority, the establishment of all

contributions as equally valid, the tolerance of open confrontation and

challenge, and the acknowledgement of patients’ responsibility for their own

lives and for the running of their wards (1996).

Patients became change-agents of self and others.

Patients also became community leaders.

The task of senior officers like myself, the

power holders in the organisation, was supportive – creating an atmosphere

where hope could develop.

It taught us to value the contributions of all the people

who worked with patients and showed us the immense power of social forces in

the life of the ward (Clark 1996).

David Clark writes of Maxwell Jones:

Jones himself said that the distinctive

aspect of the method was ‘the way the institution’s total resources, both staff

and patients, are self-consciously pooled in furthering treatment (1974, p. 29).

Jones contrasts therapeutic community with conventional

treatment.

In therapeutic communities - active rehabilitation,

democratisation, permissiveness and communalism replace the conventional

custodialism and segregation, old hierarchies and status differentiation,

customarily limited ideas and the specialized role of the doctor (1968, p. 87).

Jones refers to meetings playing a central role:

An essential feature of the organization of a

therapeutic community is the daily community meeting. By a community meeting,

we mean a meeting of the entire patient and staff population of a particular

unit or section. We have found it practicable to hold meetings of this kind

with as many as 80 patients and up to 30 staff; we think that the upper limit

for the establishment of a therapeutic community in the sense that the term is

used here is around 100 patients…it is desirable for the community meetings to

be followed by meetings of these smaller groups (1968, p. 87-88).

David Clark writes of

The centre of Belmont Life was the morning

meeting, attended by all members of the community, where all matters of general

interest were analysed. There was a system of feedback of the events of the 24

hours. This was followed, always, by a staff review session, where the main

meeting was analysed and personal contributions and reactions assessed (1974, p. 30).

Rather than been seen as a negative, crisis situations

were used to foster change:

The social organization inherent in

therapeutic community settings – both inside and outside the hospital -

strongly facilitates the productive resolution of crisis situations by

confrontation (Jones 1969, p.86).

The therapeutic

community process was largely responsible for the return of war neurosis

soldiers to mainstream society. According to Jones, at

…the group that benefited most

from the therapeutic communities were the patients (and staff) trapped in

long-stay wards. By 1980 most of those patients had left hospital (1996).

USA

Kennard (2004) refers to the writing of Boston psychiatrist

Bockoven (1956) who described ‘the heavy atmosphere of

hundreds of people doing nothing and showing interest in nothing’ in American

hospital wards in the1950s.

Sandra Bloom (1997) refers to the U.S.A. development of

therapeutic community having similarities to the UK treatment of war neurosis.

During the same

era in the

SOCIAL PSYCHIATRY, SOCIAL THERAPY AND MILIEU THERAPY

This section details some of the terms and processes

associated with therapeutic communities.

Jones defines social psychiatry as:

The preventative and curative measures, which

are directed towards the fitting of the individual for a satisfactory and

useful life in terms of his own environment (1968, p. 29).

Jones further writes on social psychiatry:

Sociocultural process is an integral part of

the treatment. The sort of social system that results is often called a

‘therapeutic community’, or in terms of social process, milieu therapy.

What distinguishes a therapeutic community

from other comparable treatment centres is the way in which the institutions

total resources, staff, patients, and their relatives, are self consciously

pooled in furthering treatment. This implies above all, a change in the usual

status of patients. In collaboration with staff, they now become active

participants in their own therapy and that of other patients and in many

aspects of the unit’s general activities. This is in marked contrast to their

relatively more passive, recipient role in conventional treatment regimes (1968, p. 85-86).

Kennard describes distinguishing features of

therapeutic communities as:

There is a ‘culture of

enquiry’, a phrase that highlights the need not only for efficient structures

but for a basic culture among the staff of ‘honest enquiry into difficulty’,

and a conscious effort to identify and challenge dogmatic assertions or

accepted wisdoms.

The basic mechanism of change can be described as this:

the therapeutic community provides

a wide range of life-like situations in which the difficulties a member has

experienced in their relations with others outside are re-experienced and

re-enacted, with regular

opportunities - in groups, community

meetings, everyday relationships

and, in some communities, individual psychotherapy - to examine and learn from

these difficulties. The daily life of the therapeutic community provides opportunities to

try out new learning about ways of dealing with difficulties (2004, p. 2).

In the context of therapeutic communities, David Clark (1974, p. 14) defines ‘social therapy’ (a term linked to

therapeutic communities) as:

… an attempt to help people to change by

affecting the way in which they live.

This is based on the observation that:

…people are shaped by the way they live,

unfortunately often for the worse (Clark 1974, p. 14).

Carstairs in the Forward to David Clark’s book quotes

another of

…the use of social and organizational means

to produce desired changes in people (Clark 1974, p. 8).

Carstairs also quotes David Clark’s third definition:

Social therapy is about personal change and

growth and living-learning experience (Clark 1974, p. 8).

David Clark suggested that social therapy could be

summarized using three words – ‘Activity’, ‘Freedom’ and ‘Responsibility’.

Jones notes the ‘experience of two centuries’ of the corroding effect of

idleness. A central focus was the potential of a community exploring freedom

and responsibility together (1974, p. 67).

The common theme through the above summary of therapeutic

community experience has been the use of social processes, especially community

meetings, as the change process. Chapters Six to Ten will detail how Neville

went way beyond the above in Fraser House.

The next section explores the intervening forces

contributing to a decline in the use of therapeutic communities within

psychiatry.

DECLINE OF THERAPEUTIC COMMITTEES

IN THE UK

David Clark, in Chapter Eight of his book ‘The Story of a

Mental Hospital: Fulbourn, 1858-1983’ (1996), details the reasons for the decline of

therapeutic committees in the UK National Health system.

In 1970, four

wards in Fulbourn hospital had been therapeutic communities and a number of

hospitals had therapeutic communities. David Clark writes of the

During the 1960s therapeutic communities had started in

many psychiatric hospitals; Henderson, Claybury, Littlemore, Fulbourn,

Dingleton and Ingrebourne became well known. In the 1980s therapeutic community

wards stopped operating, units were closed, hospitals famous for being

committed to therapeutic community principles, such as Claybury, dwindled in

size and ultimately were being closed down (1996).

The root cause is the incompatibility of an

egalitarian, democratic ward culture with the authoritarian, bureaucratic

organisation which the National Health Service has gradually become.

… the hostility of powerful senior doctors to

a system that devalued their expertise and challenged their power worked

against it, and the National Health Service Bureaucracy of the 1990s, with its

emphasis on ‘business management’, strict economy, and answerability upward

could not tolerate a system so challenging, so revolutionary and so irregular.

Enthusiasm and hope do not appear in accounting

systems.

The external response was as suspected; David Clark

writes:

A unit where patients make decisions, where

disorder is apparent and from which unacceptable demands may come, perplexes

and angers tidy-minded and harassed managers so that they readily support

demands for enquiries, disciplinary action and closure (1996).

Clark (1996) describes the

British psychiatry has moved away from an interest in

social therapy. With a wider range of new drugs available, many young

psychiatrists concentrate on improving their skill in diagnosing, assessing

symptoms, prescribing drugs and monitoring side effects.

The insecure and inadequate doctor feels far safer in a

white coat examining a half-naked patient with a stethoscope or in a

comfortable armchair out of sight behind the psychoanalytic couch, than working

in an environment where he would be open to scrutiny and criticism by patients

and nursing staff.

Clark (1996) also writes about the Nation Health Service

funding in the Seventies and Eighties:

Most of their time and energy was given to

general hospitals which had a clear traditional social structure of doctors

doing their skilled work, nurses assisting and organizing, and patients lying

passively in bed awaiting cure.

The National Health Service, David Clark writes, is now:

…where power and authority is statutorily

entrenched with administrators, consultant doctors and senior nurses and where

patients are usually treated as passive, incompetent, ignorant people whose

only task is to await the attention, skill and compassion of those paid to look

after them (1996).

Clark (1996) details

some of the lasting effects of the therapeutic community movement in the UK:

Quite a few of the practices of the

therapeutic community were by now accepted as normal in Fulbourn - mixed-sex

wards, no staff uniforms, ward meetings, staff discussion groups and open and

free discussion between professions.

Is any of what we learned

and taught still relevant? I believe most of it is. Some of the effects of the

social revolution in post-war British psychiatry remain and will I believe be

permanent. Psychiatric nurses today see their main tasks as listening to patients,

counselling them and understanding them. They know they do this best in a

supportive, friendly humane culture. Most British psychiatric wards and units

are now open door. In many units nurses, patients, and creative therapists meet

in groups and in ward meetings. This is a far cry from the psychiatric nursing

culture of the forties with its emphasis on order, uniforms, discipline and its

undertone of brutal oppression.

DECLINE OF THERAPEUTIC COMMITTEES

IN THE USA

Commencing in 1968, Paul and Lentz (1977) set up the first research in USA on long

term chronic mental patients - comparing two psychosocial change programs with

a comparison hospital treatment. One of their change programs was based on

milieu therapy (or therapeutic community) and the other on social learning

(using a token economy). 92% of the patients in the social learning program

were released with community stay without rehospitalisation for the minimum

follow up period of 18 months.

After four and a half

years of results demonstrating that the two psychosocial programs were clearly

superior to the comparison hospital, they were going to move the hospitalised

‘patients’ into the social-learning unit. However, before they could do so,

medico-political forces shut both of the psychosocial change programs down and

ended the research. Shortly afterwards, interests holding to the

biopharmacological model linked with forces within the politico-legal system to

get laws passed prohibiting many of the key aspects of the psychosocial change

programs. The effect of these laws and regulations were that aspects of

therapeutic community based programs that Paul and Lentz’s research had

empirically demonstrated as possessing considerable change power were banned.

These changes to the law left the least

useful and most expensive treatment,

namely drug-based long-term hospitalisation as the only option remaining for

long term chronic mental patients still in the hospitals. The ‘patients in and

none out’ process would ensure that this pool of patients would steadily

accumulate in the back wards.

Kennard (2004, p. 302), in referring to the success of the Soteria

House Therapeutic Community Experiment, which found the Soteria program was as

effective as neuroleptics in reducing the acute symptoms of psychosis, writes:

Surprisingly, the

success of this experiment has not spawned a host of replicas, pointing up the

conservatism of the professional establishment, the reluctance to use the

natural healing properties of normal relationships, and the hold that the drug

industry still has over treatment models.

WIDER APPLICATIONS OF THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY

In reviewing the various

settings for therapeutic community Kennard introduces the term ‘therapeutic

community impulse’ as:

….something that flows through many forms of

institutional care, including hospitals, schools, prisons and other settings

created by societies for their ill, disabled or troublesome members (and

sometimes for their brightest too). This impulse comprises a tolerance of the

expression of conflict, a desire to enable people to take responsibility for

their lives, a natural sense of democracy (not necessarily of the one vote per

person variety) where everyone has the right to information and to contribute

to decisions that affect them, and ‘a kind of shirt-sleeves informality about

the business of helping people.’ I believe it is a hardy plant because once

experienced, the capacity to work with people in this way becomes an inner

benchmark of the most humane and effective way of delivering mental health care

(1998, p. 27).

Kennard (2004) reviews the application of therapeutic community as an adaptable

treatment modality across different settings in UK, USA, in Africa and in 11

out of 15 European Union countries – including youth offenders, drug addicts,

and within prisons. Kennard refers to Kasinski’s review of the use of

Therapeutic Communities for Young People as ‘Planned Environment Therapy’ (Kasinski 2003; 2004, p. 297).

In discussing therapeutic

communities in prison, Kennard writes (2004, p. 302):

Prison may seem an unlikely

setting for a treatment model based on democratic decision-making. Yet democratic therapeutic communities have been run in prisons since

the 1960s with positive results, and today there is an increasing number within

the English prison system. The first and best known of these is Grendon Prison,

30 miles west of London, which

opened in 1962 and takes long-term male prisoners towards the end of their

sentence. Violence, sex offences and robbery are the most common types of

offence.

Once accepted, a prisoner moves to one of

five wings of 40 men, each run as a separate therapeutic community, where he

may stay for up to two years.

In Grendon:

…considerable thought is given to how the key

therapeutic principles can be adapted (Cullen 1997; Kennard 2004, p. 303).

Neville spoke to me (Dec

1993, Sept 1998) about Grendon Prison (Association of Therapeutic Communities 1999; Smartt

2001; HM Prison Grendon 2005) in the UK. Grendon has had excellent

recidivism rates (Millard 1993; HM Prison Grendon 2005) - way ahead of traditional maximum security

prisons - for over thirty years. Cullen (1997) reports the overall recidivism rate for men

who have served some time at Grendon being 33%, and for those completing their

program it falls to 16% compared with a 42 to 45% recidivism rate for the

national rate. An article in the

Birmingham Post newspaper states:

Grendon is the

only prison in Britain that operates wholly as a therapeutic community; it has

a waiting list of around 200 prisoners who want to go there and, uniquely,

independent research has just shown that prisoner who complete its therapeutic

regime are significantly less likely to re-offend when released (A Prison to Cure and Not to Punish 1998).

On therapeutic communities applications within the

criminal justice system Kennard concludes:

In the experience of the

author and other experienced practitioners in both the USA (Toch 1980) and

Europe (Cullen and Woodward 1997) therapeutic communities in prisons can be surprisingly

effective in creating a culture of openness and exploration of personal issues,

in direct contrast to the conventional prison culture, and also in reducing the

incidence of violent disturbances. Perhaps the major limitation is the acceptability

of the model to prison staff and administrators. For some staff the relaxation

of the “them and us” polarisation of officers and inmates provides a welcome

opportunity to do something worthwhile; for others it is seen as a threat to

their authority and control (2004, p. 303).

Paul Hamilton (1992) describes a therapeutic community

in K Division in Pentridge Prison in Melbourne, Australia as:

… having a valuable catalytic effect

in terms of education and work practices, as well as providing a relatively

normal environment for HIV seropositive prisoners.

Within

Many therapeutic community Drug and

Alcohol Rehabilitation Centres in

1.

Residents

participate in the management and operation of the community

2.

The

community through self-help and mutual support is the principle means of

promoting behavioural change

3.

There

is a focus on social, psychological and behavioural dimensions of substance

abuse (Gowing, Cooke et al. 2005)

The next section describes ways in which therapeutic

community processes were extended into the wider community.

REHABILITATION SERVICES,

TRANSITIONAL FACILITIES AND THE MOVE TO COMMUNITY BASED CARE

David Clark writes of the setting up at Fulbourn Hospital

of Rehabilitation Services starting in the 1970s and fully developed during the

1980s, as being another aspect of social therapy. These Rehabilitation services

were precursors to Community Mental Health.

We had moved most of our long-term patients

out of hospital into group homes, halfway houses, sheltered accommodation and

so on. We were visiting and supporting them there. We had developed an

effective system of care in the community - long before it became official

government policy.

Many hospitals emptied the wards too quickly,

with inadequate support facilities. We took longer over the process. We set up

a wider range of transitional facilities. We prepared people carefully for

discharge. We supported them in the community. We certainly had remarkably few

episodes of suicide, social breakdown or public disaster over the years while

we were opening the doors.

We developed

transitional facilities, halfway houses, group homes, sheltered accommodation.

We set up sheltered workshops and industrial units and organised supportive

rehabilitation using networks of social workers, community psychiatric nurses

and community occupational therapists, and so on (1996).

Kennard writes of the

application of therapeutic community practices to patients in community based

transitional facilities who were no longer ill or could now have their symptoms

controlled by the newer medications, and whose continued hospitalisation was

due at least partly to a loss of the skills and confidence to manage their own

lives.

As these patients left

hospital, those who remained

were those whom today are sometimes referred to as the ‘difficult to place’,

whose combination of treatment resistant symptoms and difficult personalities

keep them in need of 24-hour care. Thus although the crusading aspect of the therapeutic community approach to chronic mental illness is

relevant where total institutions are still found, today there are other

important applications in community-based housing projects for the long term

mentally ill, and the work of community

mental health teams. Small

domestic households of between 5 and 12 residents live with staff support

(either 24 hour or office hours depending on the level of need). For people

with more integrated or recovered psychoses there are regular community meetings, service users help to draw up and review their

own care plans and those of their fellow residents, and help in running the

household (2004, p. 303).

COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH - THE UK ,

USA

This section outlines the

…an appropriate

perspective for all community-based services. The emphasis on respect for the

individual, the recognition that services users have therapeutic skills, the

importance of a containing environment and awareness of the potential for

splitting within teams and organizations have been noted as some of the

contributions that the therapeutic community approach can make to the work of

community mental health teams (Kennard 2004, p. 300)

United States

Community Mental Health was promoted in the United States

as a new wave of ‘expanded mental health care’ (Citizens Commission on Human Rights 2005).’

Given this aspiration, the organisation LA Voice writes:

There's no question that deinstitutionalising the

mentally ill ended (for the most part) the cuckoo's-nest

horrors of 1950-60s mental hospitals. But it also consigned people with

a horribly difficult-to-manage, stigma-ridden lifetime illness to a ragged net

of jails, outpatient programs and halfway houses from which the Legislature

often enjoys siphoning money. End result? People get dumped back onto the

street.

The Times points out that 34% of the 83,347 homeless in

greater L.A. are severely mentally ill; 47% of the total are chronic substance

abusers and 19% are veterans (though it doesn't say how much those three

numbers intersect) (LA Voice 2005).

Given the concerns, across

each State in the

Mediation has been evolved in some parts of the world as

a way of settling issues in dysfunctional families (Carlson 1971). One such example is the Ontario Family

Mediation Centre (2005), which was highly regarded by Neville (July

1998).

Community Mental Health in the UK

Clark (1996) writes that as a result of the social revolution in

post-war psychiatry in the UK, the care of people with long-term mental disability

has been changed utterly:

Very few of them are now in hospital wards.

Many live in the community, with their families or in sheltered accommodation.

They attend day centres and workshops and are supported by teams of social

workers and community nurses. We have created in

The 4 November 1999,

BBC program ’Background Briefings’ spoke of care in the community representing ‘the biggest political

change in mental healthcare in the history of the NHS.

It was the

result both of social changes and political expediency and a movement away from

the isolation of the mentally ill in old Victorian asylums towards their

integration into the community. The aim was to ‘normalise’ the mentally ill and

to remove the stigma of a condition that is said to afflict one in four of the

British population at some time in their lives.

The main

push towards community care as we know it today came in the 1950s and 1960s, an

era which saw a sea change in attitude towards the treatment of the mentally

ill and a rise in the patients' rights movement, tied to civil rights

campaigns.

The 1959

Mental Health Act abolished the distinction between psychiatric and other

hospitals and encouraged the development of community care (BBC News

2005).

An Internet source document from the UK NGO

‘Mind’, formerly ‘The National Association for Mental Health’ entitled ‘Key

Dates in the History of Mental Health and Community Care states:

From 1955

onwards, psychiatric in-patient numbers began to slowly decrease due to the introduction

of social methods of rehabilitation and resettlement in the community, and the

availability of welfare benefits, as well as the introduction of antipsychotic

medication (Mind 2005).

The same ‘Key Dates’

document identifies 1961 as the

year Enoch Powell, as Health Minister, made his famous ‘Water Tower’ speech to

the Annual Conference of the NGO Mind.

He envisaged that psychiatric hospitals would

be phased out and care provided in the community. Powell’s plan was for

‘nothing less than the elimination of by far the greater part of this country’s

mental hospitals as they stand today’ (2005).

The ‘Key Dates’ document refers to:

The Hospital Plan for

In-patient numbers continued to fall, but

many local services were not yet in place. A new group of ‘long-stay’ patients

began to accumulate in the hospitals. The era of community care had begun and

this has remained official policy ever since (2005).

Sir Roy Griffiths’ 1988 UK report, ‘Community Care:

Agenda for Action’ was a precursor to the Community Care Act of 1990, that set

up community care as it has operated through the Nineties

(Mind 2005).

In 1998 in the

Care in the community has failed. Discharging people from

institutions has brought benefits to some. But it has left many vulnerable

patients to try and cope on their own. Others have been left to become a danger

to themselves and a nuisance to others. A small but significant minority have

become a danger to the public as well as themselves (Mind 2005).

Burns and Priebe (1999, p.

191-192)

outline issues in Mental Health Care in the UK:

The past few years have seen mental health

services in

We’re mad to trust shrinks – Daily Mirror, 9

February 1996.

The current, pervasive

opinion is that English mental health services (especially in cities) are

unacceptably poor (Deahl and

Turner 1997).

Burns and Priebe (1999, p.

191-192)

also refer to comments by Frank Dobson (1990):

The Secretary of State for

health, Frank Dobson, has recently pronounced that ‘community care has failed’,

and his predecessors expressed their lack of confidence by imposing a succession

of increasingly restrictive legislative requirements – the Care Programme

Approach.

Burns and Priebe detail

shortcomings:

There are undoubtedly

serious short-comings in the English services. These include the excessive

preoccupation with risk, the limited therapeutic involvement of consultants and

the shortage of services for patients with less severe mental illnesses, to

name just a few (1999).

In the same article Burns

and Priebe also comment on considerations of clinical effectiveness:

Service delivery is

generally transparent and subject to clinical audit and a widespread

consideration of clinical effectiveness. English psychiatrists, correctly

preoccupied with the problems generated by the split between health and social

care, seem rarely to reflect on the degree to which services are fragmented elsewhere.

By international standards our services are extraordinarily straightforward and

well co-ordinated (1999).

They also provide the

following contextual information:

Neither one of us doubts the

real problems that face modern mental health services. The rules of the game

are changing. Family and social changes make coping with severe mental illness

increasingly problematic. Public expectations are rising, and in our current,

very visible position, balancing therapy with social control is highly

delicate.

There is no shortage of

advice about how to reform the mental health services being proffered by

pressure groups and voluntary bodies. In many cases their conviction may far

exceed evidence for the feasibility or value of their proposals (1999).

Community Mental Health in Australia

Community Mental Health in

As one indicator of the current status of

community mental health care the Weekend Australian newspaper 16 July 2005 ran

a headline ‘Time to Get Mentally Ill Out of Jails’:

Leading psychiatrists have admitted that a

twenty-year policy of treating mentally ill patients in the community has

failed. The psychiatrists are demanding radical review of mental health care

claiming prisons have replaced asylums as holding centres for the mentally ill.

Those calling for a new approach include many of the architects of the current

policy of de-institutionalisation, which lead to the closure of psychiatric

wards and institutions around the country.

A recent study by the Corrections service

found that 74% of prisoners in NSW suffer from a psychiatric disorder with

almost 10% suffering symptoms of psychosis (Kearney and Cresswell 2005).

SELF-HELP AND MUTUAL AID GROUPS

Another development in the

1960’s was psychosocial self-help/mutual aid groups where people with mental

malfunction provide each other mutual support without the presence of mental

health professionals. Historically, governments and their agencies, as well as

private service providers, have provided care to the mentally disabled as a

funded service. After self-help and mutual aid processes were evolved in

therapeutic communities, ex-patients of these communities began forming their

own self-help groups in civil society. This led to the growth of voluntary

not-for-profit psychosocial self-help group movement in the

Kyrouz,

and Humphreys (1997) carried out a review of research carried out in the 1980s

and 1990s on the effectiveness of self-help mutual aid groups. Their review

primarily covered studies that compared self-help participants to

non-participants, and/or gathered information on multiple occasions over time

(that is, “longitudinal” studies).

They summarise findings of five research studies on

mental health groups as well as research on self help groups focusing on

suffers of bereavement, diabetes,

cancer, chronic illnesses as well studies on self-help group for caregivers as

well as groups for elderly people.

Kyrouz, and Humphreys (1997) report:

Most research studies of self-help groups have found

important benefits of participation.

ORGANIZATIONS,

NETWORKS AND MUTUAL HELP PROVIDING SUPPORT AND SUSTENANCE TO MARGINAL PEOPLE

Healthy Living Centres

Influenced

by the Peckham Experiment mentioned previously, the

Its

aim is to improve health through community action and particularly

to reduce inequalities in health in deprived areas.

Healthy living centres will

take various forms and may exist as partnerships and networks rather than as

new buildings. They are based on a recognition that determinants of

poor health in deprived areas include economic, social, and

environmental factors which are outside the influence of

conventional health services (BMJ

Editorial 1999).

Everyday Life Mutual Help

Rowan Ireland (1998),

a Melbourne sociologist had been researching an urban renewal social movement

among the extreme poor in São Paulo, Brazil in the late eighties.

Ireland refers to Evers' (1985) writings

on new social movements in Latin America. Like

Natural Nurturers in Everyday Life

Resonant with the São Paulo

experience above, a report of a visit (where I was a member of a international

team) to the Southern Philippines war zone of Pikit, Mindanao identifies

‘natural nurturer networks’ among the local rice farms living in the war zone

as an integral aspect of ongoing social support among local people:

Given the limitations and

the short period allotted, the team achieved the objectives of the pre-test,

especially in drawing out local contexts, identifying local healing ways, and

natural nurturers says international team member and UP CIDS PST research

fellow, Faye Balanon. More importantly, there is the need to help identify

local psychosocial support systems, especially in the areas struck by

calamities, and to identify people in the local cultural context – the natural

nurturers who could support the psychosocial needs of the community after the

team has left (Balanon

2004).

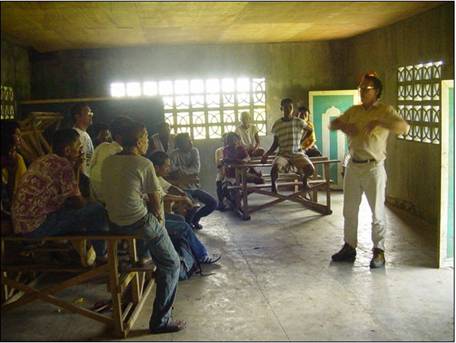

Photo

3

Engaging with Muslim Men’s Group in Pikit Area – used with permission

Chapters Twelve and Thirteen extend this theme of natural

nurturers.

POSSIBLE FUTURES

As in the call to recreate the old asylum culture in Australia

(Kearney

and Cresswell 2005), the same trend is emerging in the UK.

A malignant

trend in English society in the 1990s is the growth in the number of gaols and

secure institutions.

Wherever society locks up people it dislikes and pays other people to

keep them in, an oppressive and cruel culture is likely to develop. If

society designates these prisoners ‘insane’ and hires doctors and nurses as

gaolers, they will create the same medicalised, hypocritical gaol culture as in

the old asylums (1996).

SHIFTS IN PSYCHIATRIC MODELS

This section returns to the

theme of psychiatric models and explores forces influencing them in the past

few years. Burns and Priebe (1999, p. 191-192) writing of the UK psychiatric experience

point out the players involved in the underlying economics and review of

effectiveness of mental health service provision:

Mental

health care is, with few exceptions, within the public domain, and service

planning is not solely driven by the economic interests of service providers

and insurance companies.

The powerful forces

associated with psychiatric paradigm shift mentioned at the beginning of this

chapter are currently being confronted by Victorian Workcover, a State body in

The five core principles reflect contemporary practice

in injury management and focus on:

1.

a demonstration of measurable

treatment effectiveness

2.

a biopsychosocial approach for the

management of pain

3.

empowering workers to manage their

injury

4.

treatment goals that focus on

function and return to work and

5.

the delivery of treatment based on

the best available evidence.

With respect to the

‘psychosocial’ component of biopsychosocial,

the terms ‘functional

overlay’, ‘somatoform reactions’ or ‘psychosomatic reactions’ are used when

people have a psychological overlay suppressing or inhibiting

physiological function. Typically, Workcover claimants with functional overlay

are referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist. Rather than the previous norm

of expert based assessment, the clinical framework requires the use of

standardised outcomes assessment of:

1.

Physical

impairment

2.

Activity

limitations

3.

Life

participation restrictions

‘Life participation

restrictions’ asks for considerations on a wellness continuum rather than

nosological diagnoses of discrete or dichotomous conditions.

For psychiatrists and other

caregivers to continue to receive funding for their Workcover claimants, they

need to demonstrate measurable treatment effectiveness

resulting in the enhancement of at

least two of the above three domains. Independent standardised outcome

assessment has to be used. There is also a provision that the treatment must

focus on empowering the claimants to manage their own injury. Another provision

is that treatment goals must be functional and focused on a return to work.

It is understood that the Transport Accident Commission is likely to introduce

a similar Clinical Framework. This

outside intrusion into the power domain of psychiatrists, psychologists, and

other professionals is being strongly resisted by them (from discussion at an

Australian Wellness Association Forum in

Having a ‘return to work’

focus is isomorphic with a concern to have people returning to functional

living in society rather than being warehoused in asylum back wards like

soldiers with war neuroses. The Clinical Framework does hold a space for a

psychopharmacological approach; drugs may be an aspect of treatment. The

framework changes the patients’ role from being a passive and dependent upon a

professional expert to having an active self-help role with a functional return

to work focus. The potential role of Neville’s biopsychosocial processes in the

context of the Workcover Clinical Framework is discussed in Chapter Ten, Eleven and Thirteen.

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL, THERAPEUTIC

GOVERNANCE AND

GLOBAL SOCIAL CONTROL

Vanessa Pupavac (2005) in her paper ‘’Therapeutic Governance: the Politics of Psychosocial

Intervention and Trauma Risk Management’ argues the international psychosocial model and its

origins in an Anglo-American therapeutic ethos is being used for social control

via pathologising of Third and Fourth World countries by wide interests in the

First World. Her paper argues that

‘psychosocial approaches jeopardise local coping strategies’ and identifies ‘the potential political, social and psychological

consequences of the pathologisation of war-affected societies’. Her paper

concludes ‘that therapeutic governance represents the reduction of

politics to administration’. Pupavac argues that powerful first world entities

assume pervasive pathology exists in third and fourth world societies and take

action that strengthens that assumption, and then uses the claimed pathology to

take on a ‘therapeutic governance’ role on behalf of ‘helpless’ people.

Power is not exercised by the ostensible subjects

of rights, but by international advocates on their behalf.

Effectively, the psychosocial model involves

both invalidation of the population’s psychological responses and their

invalidation as political actors, while validating the role of external actors.

Where populations are experiencing a

curtailment of self-determination and a questioning of their moral capacity, it

should be no surprise if psychosocial professionals find a relatively high

instance of depression - the link between a sense of control and mental health

is well established. However, the presence of depression does not vindicate

therapeutic governance, rather the reverse. It is the functionalism of

therapeutic governance that needs to be examined. Ironically, the unprecedented

regulation of people’s lives and emotions under therapeutic governance risks

populations’ mental health. That populations do not succumb to the

pathologisation of their condition under therapeutic governance in greater

numbers is testimony to people’s capacity and resilience.

Chapters Seven and

Thirteen revisit the themes of therapeutic governance and social control

where Neville reverses the above framing – where the locus of governance and

control for re-constituting collapsed society is with the marginalized fringe

acting in mutual help. Neville’s process entailed relational governance.

SUMMARY

This chapter has provided a brief background to my

research on therapeutic communities and community mental health in