Chapter

Nine – Fraser House Transitionary Processes

INTRODUCTION

This chapter looks at Fraser

House small group process and the many other change processes evolved at Fraser

House. Margaret Mead’s visit is discussed and Neville’s adaptation of Keyline

to Cultural Keyline is analysed.

SOCIAL CATEGORY

BASED SMALL GROUP THERAPY

Just like Big Group,

Small Groups were run like meetings. Typically, one staff person ran the Small

Group and another staff person was a process observer, on-sider and trainee.

Small Groups were mainly conducted by the nurses, with some groups being lead

by medical officers, the social worker, and the chaplain. The chaplain ran some

spiritual groups at Fraser House. The Fraser House Handbook specifies the nurse

therapist role in Small Groups (refer Appendices 7 & 8):

The role of the Small Group therapist and

observer has always been the province of the nurse in Fraser House, and

represents part of the rise in therapeutic status. Nurses have become

therapists in their own right.

The first essential

in taking a group is to see it as a meeting, and like all meetings, there is a

need for a chairman to conduct affairs and keep issues to the point.

The initial function

of the therapist is to see that the group functions as a group (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 4, p. 18).

The Handbook then

gives detailed specifying of group process. Sections of the Handbook on the

Nurses Roles and Big Group process are shown in Appendices 7 and 8.

Small groups were

held from 11 AM to 12 Noon after a half hour refreshment break following big

group. They were preceded by the staff discussion over morning tea. After

evening Big Group and a similar thirty-minute staff discussion period, Small

Groups were run from 8 PM to 9 PM. During the staff discussion, patients and

visitors had an informal morning tea together separate from the staff. All

groups and the refreshment break ran strictly to time. Another staff discussion

meeting took place after Small Groups to ensure all staff was well briefed on

unfolding contexts.

In an April 2003 email Phil

Chilmaid wrote:

There were several ways to

follow up progress and issues: inter-staff verbal exchange at shift change,

ward report books, patients’ progress notes, and at various times, small group

report books, and a large sheet of butchers paper ruled up with boxes for all

the weeks programs and events so staff could come in after a gap or next shift

and follow themes and developments.

Generally, nearly all the outpatients (typically,

friends, workmates and relatives of patients) attending Big Group stayed and

were allocated to the various Small Groups in both the morning and evening

sessions. It was expected that outpatients attend both Big and Small Groups.

There were ten or more concurrent Small Groups typically made up of between 8

to 12 people, or more per group.

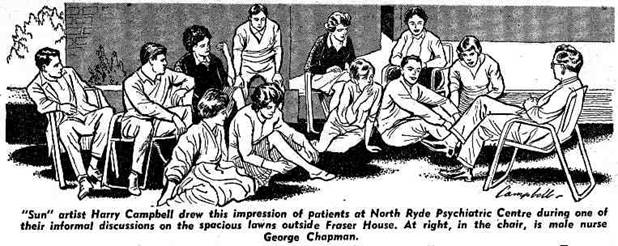

Drawing 1 A Sketch of a Fraser House

Small Group by Harry Campbell

The above illustration by "Sun" artist Harry

Campbell of patients at Fraser House was published in The Sun Newspaper, 17

July 1963, p.28 [Also included in Neville’s News clippings (Various Newspaper Journalists 1959-1974, p.

33-34)].

Recall that upon Tikopia there was constant linking

within and between people of differing generations, gender, clan, village,

locality, status (chief/non-chief families) and occupation, that is, between

differing sociological categories. Similarly, Neville cleaved Fraser House

family-friendship networks and inter-patient factions by sociological category.

Neville’s aim was to create self-organizing communal

living, which may impact upon and create shifts away from isolation and destructive

cleavage, or make functional cleavage in entangled pathological networks.

In

supporting mad and bad people with their dysfunctional family-friendship

networks live well with each other, Neville’s view was that one of the primary

healing processes that was both structured into and continually and pervasively

at work within Fraser House, was the day-to-day lived-life dynamic healing

interplay of social cleaving and unifying processes – the same processes that

have been discussed in talking about Tikopia. Neville would set up scope for

micro-experiences creating very strong forces cleaving pathological

entanglements, as well as forces forging functional bonds within and between

people. Typically, patients arrived with a very small family-friendship network.

Both the sociological category and the composition of

small groups varied daily. All the small groups at any one time were based on

the same category.

The social categories were:

(i)

age

(ii)

married/single

status

(iii)

locality

(iv)

kinship

(v)

social

order (manual, clerical, or semi-professional/professional) and

(vi)

age

and sex.

Friday’s

Small Groups were made up according to both age and sex for both staff and

patients. This was the one exception to the non-segregation policy. Often

inter-generational issues, including sexual abuse issues, were the focus of

these Friday groups.

People in pathological social networks would be all

together with everyone else in Big Group. However, because of the

continual changing composition in small groups, the members of these

pathological networks were regularly split up (cleavered) for the small group

sessions. Age grading was deemed very important, as it is one of the basic

divisions in society. Neville told me (July 1998) that the thinking was that

age grading sets a context for the production of personality changes to prepare

the client for life outside Fraser House. Age grading also allowed space for

sorting out inter-generation pathology that was very prevalent. For example,

Appendix 13 contains a note that at one time the Canteen was staffed only by

people under twenty years of age. This would have created scope for sustained

inter-generational relating with suppliers and customers.

Because of the number of categories, any visitor coming

regularly on certain days of the week would find that they would be attending

groups based on differing categories. For the small groups based on locality,

After a time at Fraser House these individual patient family/friendship

networks would expand to have members with cross-links to other patient’s

networks, and with a continual changing Unit population with overlap in stays,

these nested patient-networks became very extensive. As well, all these people

had Fraser House experience in common, and a common set of mutual support

skills. The critical role of locality and Neville’s use of locality in this

increase in the size and functionality of patient’s social networks is entirely

resonant with Indigenous links to place, and the significance of place and

placeform in Keyline.

CHILD-PARENT

PLAYGROUPS

Webb and Bruen (1968) wrote up research relating to the first 13

weeks of Multiple Child-Parent Therapy in Fraser House – called by some, ‘the

mad hour’. Median attendance was 15 parents and sixteen children (aged 14 and

under). This therapy was held in the same room as Big Group. All chairs were

removed and ‘free play’ items were provided - including saucepans, games,

balls, clothes as well as chalk and a blackboard. Attendance for parents and

their children under 14 was compulsory and doors were looked to prevent people

leaving; although parents with unproblematic relations with young infants were

not required to bring them. Outpatients visiting Fraser House with children

under 14 also attended the parent-child groups. As with other groups at Fraser

House, there was a spread of diagnostic categories[1]

among the people attending, as well as a spread of under-actives/over-actives

and the under-controlled/over-controlled (Bruen Dec, 2005).

The first half hour was a free period. Parents asked what

they were supposed to do. The only instruction was ‘parents are free to play

with or discipline their children as they see fit’. Staff were told that during

the free period they were to observe but not intervene unless physical damage

seemed imminent. Staff could move around and talk to parents or play with

children; however, staff were not to organize anything.

In the first few weeks these groups were extremely noisy,

rowdy and stressful for parents, staff and children alike, especially the free

period where staff were almost as overwhelmed as the parents.

The second half hour was usually structured with finger

painting or routine group therapy. The third half hour was a reporting session.

After that session the attendees were divided into three groups run by staff -

parents (one hour session), children 8-14 (one hour session) and younger

children (half hour session). The half hour with the younger children was

described as ‘utter chaos’. There was then a final reporting session for staff

for a half hour.

Initially, nearly all parents expressed considerable

hostility towards the group and towards the staff who set up the group. During

subsequent groups, parents grudging acknowledged that children enjoyed it. In

an email exchange Bruen stated (December 2005) that:

Even

having parents become hostile towards us succeeded in bringing them closer to

their children.

The free period was originally an arena for staff to

watch interactions that emerged. Initially parents were unable and unwilling to

go near or engage with their children – they were emotional strangers. ‘Getting

together’ as a family was a rare event in these people’s lives.

For six weeks the group was a provoking agent. After six

weeks parents grudgingly admitted that the children enjoyed the sessions (Webb

& Bruen, 1968, p. 52). After 9 weeks, successful whole family discussions

were starting. Parents began playing with each other and play was being

organised by parents with and between whole family groups. Whole families began

to get together and enjoy each other’s company. A major therapeutic role of the

groups was having parents showing pleasure and amazement in having for the first

time their children approaching them to play with them, and if parents did

this, that it would not have disastrous consequences.

During the thirteen weeks covered in the Web-Bruen

research, the attendees were also attending Big and Small Groups, and discussion

about the Child-Parent Groups was often raised in both of those forums.

Terry O’Neill used to facilitate this upstairs child-play

segment as a volunteer psychologist after Warrick Bruen left. (I received my

counselling skills training from Terry in the late Seventies.) Terry told me

(Oct 1998) that on his first evening alone with the children (8-14), so much

emotional energy had been generated during the first segment, ‘playing’ with

their parents, that the nature of the frenzied play upstairs was scary. Some of

the older children were kicking a soccer ball round like a deadly missile.

Everyone had to be super alert not to get his or her head knocked off. Terry

said (Oct 1998) that having a number of disturbed children in play therapy in

these evening sessions stretched his skills to their limit.

The substantial change towards good parent-child

relations during free play in these child-parent groups is another example of

‘provoking’ or ‘perturbing’ the families and tapping into functional self-organizing

aspects in the context of all of the other Fraser House changework.

INDIVIDUAL THERAPY

When deemed appropriate, face-to-face therapy between two

patients, a patient and a nurse, or a patient and a doctor was held. Even in

this individual therapy, the central focus was inter-patient relationships.

Encouragement was continually given to ‘bring it up in the group’.

While it was recognized that during some crisis times a

patient may need support by a doctor or nurse, most face-to-face therapy was

informally between patient and patient as they went about everyday life, with

the wider community always a background.

RESEARCH AS

THERAPY

Neville

commenced his postgraduate diploma in sociology shortly after Fraser House started

and completed it in 1963. Neville spoke (July 1998) of Fraser House being an

informal Post Graduate Research Institute, and of the Unit being the most

advanced Social Research Institute in Australia.

Neville had pointed out to me that Franz Alexander had

observed the potential for healing of the caring relationship between Freudian

analysts and patients (Alexander 1961). Similarly, Elton Mayo (Trahair 1984) had found in the Hawthorne experiments

amongst workers in the early part of this century, that the change component

was not so much the various ‘treatments’ of the research - rather that it was

that the researchers were acknowledging the workers’ dignity and worth and

showing an interest in them. Change was linked to the emotional experience of

being research subjects. Similarly to Mayo’s work, Fraser House patients and

staff were the focus of continual research by Fraser House researchers and the

outside research team headed up by Alfred Clark. Patients were being

continually asked to reflect on themselves, other patients, other staff, Big

Groups, Small Groups and on every aspect of Fraser House and aspects of wider society.

Through all of the research, patients learned about the difference between

quantitative and qualitative research as well as about the notions ‘validity’,

‘reliability testing’ and ‘trustworthiness’, and how these are very useful

notions as part of living in a modern community, especially one with extensive

pathology. Patients also became involved in both qualitative and quantitative

research data gathering as well as discussing the results and implications of

the research.

During 1963-1966, research by nurses in Fraser House was

supervised by Neville (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 12, p. 69). Neville gave preliminary training to nurses

in research methods and also trained the social worker in research methods. At

one time Neville arranged a Fraser House Research workshop with 25 associated

projects (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 12, p. 86-99). As an example, Fraser House residents were

involved in rating patient participation and improvement (refer Appendix 16).

In answering, patients were not only being encouraged to notice healing

micro-experiences (experience of little bits of behaviour that may contribute

to healing), they were receiving the strong positive emotional experience that

what they thought and felt about things mattered and was of value. Having come

from conflicted family environments where contradictory communication (Laing and Esterson 1964) was the norm, doing reality testing and

checking the practical usefulness, validity and relevance of their observations

was valuable. Patients and outpatients would start discussing a very diverse

range of topics and in the processes evolve their capacities in forming,

expressing and evaluating opinions and making insightful and useful

observations about human interaction.

VALUES RESEARCH

Another example of treating patients with respect,

dignity and worth was asking them to explore and give answers to questions

about their value systems. Neville carried out extensive values research (1965a) based on the concepts of Florence Kluckhohn (1953, p. 342-357). A list of the questions that were asked in

Neville’s Values Research is in Appendix 17. This Fraser House values research

was followed up by questionnaires being completed by over 2,000 people in

Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane - the three largest cities in

In Neville’s view (Dec 1993), substantially shifting core

values amounts to shifting culture. Neville also stated that at the time, this

values research was, in all probability, the most extensive research on values

that had been done anywhere (Clark and Yeomans 1969, p. 20-26).

Appendix 18 and 19 lists inventories developed and used

at Fraser House (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 4, p. 43, Vol. 11). These inventories enabled the putting

together of a holistic psycho-social emotional mindbody portrait of each

patient and outpatient’s whole life, covering presenting matters, recent past,

post-school period, childhood, as well as work history and recreational

activity. This is consistent with the holistic socio-emotional focus of change

at Fraser House. Reflecting these stories back to patients engaged in

reconstituting their unfolding story had functional value.

Despite being extremely busy with every aspect of Fraser

House and its links into the community, Neville was very active in research and

writing up papers. He was an active presenter at conferences and other

professional meetings. Appendix 20 contains three Tables (A, B, and C) listing

fifty seven of the extensive body of Neville’s research papers and monographs

mentioned in his collected papers in the Mitchell Library. Many are undated

though come from the 1959-1965 period.

Group and crowd behaviour during big groups was a

constant research theme. For example, in a filenote called ‘Colindivism’ (1965a) Neville describes the interactive nature of

collective and individual behaviour in Fraser House.

Patients knew that all manner of data was being collected

about them relating to demographic and socio-economic data, length of stay,

participation by their friends and relatives and the like. Research outcomes

were discussed with patients.

Within

a connexity based Cultural Keyline frame it made absolute sense to connect

patients to the interconnection and inter-dependence of aspects of society at

large. Psychiatric patients and ex-prisoners were asked their attitudes towards

overseas trade with SE Asia, or about landscape planning and urban renewal in

Neville

told me (Dec 1993, July 1998) that a process he used to protect Fraser House

was that a number of research workers from

Bruen told me (Aug, 1999) that Margaret Cockett made

sociograms of networks within Fraser House using the concepts of ‘power’,

‘opinion leaders’, ‘leaders’ and ‘influence’. The conducting of this research

was later confirmed by Margaret Cockett (April 1999). Regrettably, this

research was among the materials discarded by

Sociogram based research in Fraser House recognised that

P.A.’s three primary landforms (main ridge, primary ridge and primary valley)

embody horizontal unity in the context of vertical cleavage though no reference

to Keyline is made. Neville and other researchers at Fraser House used the

above notions of horizontal unity in the face of vertical cleavage

in doing sociogram research into the friendship patterns among staff and

patients in Fraser house (Clark and Yeomans 1969, p. 131). A ‘glimpse’ of Neville’s use of Tikopia’s

cleavered unities is in Clark and Yeomans’ book, ‘Fraser House’ under the

subheading ‘Cleavages’ relating to the sociogram research (Clark and Yeomans 1969, p. 131). Not surprising, this sociogram based

research showed that Neville was only staff member:

with a link, by means of a mutual tie, into the

genotypical informal social structure…. (Clark and Yeomans 1969, p. 131).

Sociogram 1 Sociogram Showing the Friend Network in

Fraser House.

This

finding is fully in keeping with Neville’s notion of devolving responsibility

and reversing the status quo. It was also in keeping with Neville’s hands-off

though being profoundly and sensitively linked that he was enabler on the edge

of the informal social structure.

Apart

from research as therapy, Fraser House research served at least two other

functions. Firstly, the results were fed back in to modify the structure,

process and action research in the Unit. For example, the critical and

destructive role of extremely dysfunctional families and friends in holding

back patient improvement became clearer to staff and patients alike from both

experience and research over the first three years. Greater efforts were then

made to involve these networks. Secondly, the research was used to protect the

Unit and ensure its survival, at least for a time.

PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH STUDY GROUP

Neville set up the Psychiatric Research Study

Group on the grounds of the

The Study Group provided a space where ideas

were enthusiastically received and discussed. Some participants had been

finding it hard to get an audience for their novel ideas within the climate of

the universities of the day. The Study Group was another cultural locality.

Anything raised in the Study Group that seemed to fit the milieu in Fraser

House was immediately tested by Neville in Fraser House. In trying something to

see if it worked, Neville spoke (July 1998) of ‘the survival of the fitting’.

At one time there were 180 members on the

Psychiatric Research Study Group mailing list. Neville wrote that the Study

Group:

…represents every field of the social and

behavioural sciences and is the most significant psycho-social research

institute in this State.

The Psychiatric Research Study Group

maintains a central file of research projects underway throughout NSW and acts

in an advisory and critical capacity to anyone planning a research project’ (Yeomans,

N. 1965a, vol. 4, p. 24).

Meetings were held monthly at first at Fraser

House and then elsewhere.

WORK AS THERAPY

The canteen provided one context for using

work as therapy. Another example was the patients winning a contract to build a

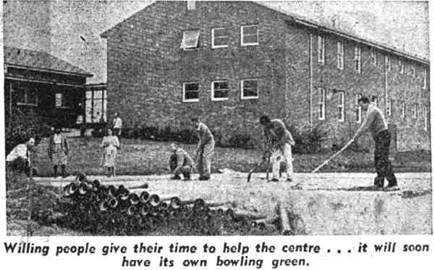

Photo

1 Patients building the Fraser

House bowling green in the Sixties - a photo from the Sydney Morning Herald (11

April 1962).

The

above photo accompanied an article entitled ‘The Suicide Clinic’.

Photo

2 I took this photo in June 1999 showing brick retaining wall and

Bowling Green behind the wire-mesh fence

The

above photo shows the Bowling Green area behind the fence that was levelled out

by patients with hand tools. The retaining wall was also built by the patients

and it has stood the test of time - still vertical. To reaffirm, a very important type of work

that some of the patients became very adept at was being therapists and

co-therapists in group and everyday contexts. All my Fraser House interviewees

confirmed (Aug, 1998 and April, 1999) that often the most insightful therapy in

everyday life and groups within the community was by patients.

Patient

based therapy was offered though the letter from the President of the

Parliamentary Committee (the letter is included as Appendix 11) (Yeomans,

N. 1965a, Vol. 2, p. 11).

MARGARET

MEAD VISITS FRASER HOUSE

The Anthropologist Margaret Mead visited

Fraser House as the Co-Founder (1948) and ex-President (1956/7) of the World

Federation for Mental Health (Brody 2002).

Separate discussions with Margaret Cockett and Neville (Aug, 1999)

cross-confirmed the following material about Mead’s visit. Margaret Cockett

informed me that Margaret Mead was introduced to Fraser House by an

anthropologist friend of Margaret Cockett in the NSW Housing Department who had

told Mead about Fraser House when Mead came to visit her. Cockett told me that

initially Margaret Mead could not believe what she was hearing and came to

Fraser House to check it out for herself. Mead was escorted throughout the day

by Margaret Cockett, the Fraser House anthropologist psychologist. Margaret

Cockett recalled Margaret Mead saying that she was very taken with the concept

of therapeutic community and had visited many such communities in different

places.

Mead very ably conducted the morning Big

Group and ran a small group when she visited Fraser House (discussion with

Neville, April 1999 and Margaret Cockett April 1999). Margaret Cockett

described Mead as being ‘absolutely on the ball’ in the role of leader of both

Big Group and one of the Small Groups. Margaret Mead also took the regular half

hour staff group meeting that followed the Big Group.

A

number of senior people from the health department joined Margaret Mead for

lunch where according to Margaret Cockett, Margaret Mead held court and

demonstrated that she was clearly ahead of every one of them in their

respective specialist areas. Margaret Cockett suspects that it was Margaret

Mead’s glowing report to these people in the NSW health establishment hierarchy

that made things just a little easier for Fraser House for a while. Neville

said (April 1999) that at that time Mead visited Fraser House, the medical and

psychiatric profession saw no relevance whatsoever for anthropology in their

professions. Margaret Mead gave the ‘big thumbs up’ to Fraser House to these

Department Heads, ‘heaping praise’ on every aspect of the Fraser House

therapeutic community.

Margaret Mead also chaired the Psychiatric

Research Study Group when she visited Fraser House (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 12,

p. 68).

Dr.

Margaret Mead, world famous anthropologist who visited Australia last year

attended a meeting of the Psychiatric Research Study Group and also stated that

she considered Fraser House the most advanced unit she had visited anywhere in

the world (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 12,

p. 69).

All

of my informants spoke of the dense holistic inter-related ‘total’ nature of

Fraser House. Neville (Aug 1999) told me that Mead also stated that Fraser

House was the only therapeutic community she had visited that was totally a

therapeutic community in every sense. Cockett, in talking about Mead’s

feel for Fraser House’s totality and completeness said that Mead spoke of

Fraser House as the most total therapeutic community she had ever been to.

(Note that the above sense of ‘total’ differs from Goffman’s use of ‘total’ as

a term describing entities like monasteries, prisons, asylums, and warships

that bracket people off from everyday life. While a ‘total institution’ in

Goffman’s terms (1961), Neville said that Mead was particularly taken with the

fact that important others were required to regularly visit patients in Fraser

House, and that one patient, having a horse as the only ‘important other’ in

her life, was allowed to have the horse tethered grazing on the lawns of the

hospital just outside Fraser House. A few other patients had a cat or a dog as

their ‘important other’. I took the photo below in August 2000. It shows Fraser

House through the trees and the grounds outside Fraser House where the horse

grazed.

Photo 3 A photo I took in June 1999

of the place where the horse grazed at Fraser House

Reading the Fraser House Committee Structure

(Appendix 13) may give a further feel for the totality and completeness that

Margaret Mead, spoke of when describing Fraser House as the most Total therapeutic

community she had ever been to.

Margaret Cockett (Aug, 1999) and Neville (Dec

1993 and August 1999) confirmed that Mead also stated that Fraser House was the

only therapeutic community that was totally a therapeutic

community in every sense. Similarly, in the forward of Clark and

Yeomans’ book about

Fraser House, Maxwell Jones, the pioneer of therapeutic communities in the

Throughout the book is the constant awareness

that, given such a carefully worked-out structure, evolution is an inevitable

consequence

(Clark and Yeomans 1969, Forward, p. vi).

It is this ‘total’ aspect of Fraser House

(and

Recall that Maxwell Jones had said of

therapeutic community in the

It does not amount to a treatment methodology

in its own right but complements other recognized psychotherapeutic and

pharmacological treatment procedures (Jones 1969, p. 86).

Neville had created a total therapeutic

community where every aspect was transformative.

To continue the theme of setting up

inevitable change in self-organising systems, I will now detail my findings

about Cultural Keyline.

Margaret

Cockett (Sept 2004) told me that Neville and everyone connected at Fraser House

where constantly trying out new things. Everything was extremely fluid. Someone

would come up with an idea and it would be immediately woven in. In Margaret’s

view Neville tended to make connections between some

new thing they were trying out and what they did on the farm. It seems that Neville’s sensing of what

Keyline adapted to the psychosocial may be, emerged out of Fraser House’s

dynamic eclectic process rather than being an intellectual exercise imposed on

Fraser House. Theory emerged from theorein (pretheoretical theorising) (Pelz 1974) and process.

Neville

first mentioned the term ‘Cultural Keyline to me when I was staying with him in

Yungaburra in December 1991 and when I asked Neville to expand on what he meant

by the term, Neville changed the topic saying that I already knew all about it.

I was puzzled by this. I again asked in December 1993 and he told me to read

all of his father’s Keyline writings and then I may discover Cultural Keyline

in my own actions. After his death in May 2000 I realised that Neville was

aware that through his subtle modelling of his behaviour in my presence, I had

absorbed aspects of his way and regularly used Cultural Keyline in my action

research in his presence, even though I did not know my actions were consistent

with Cultural Keyline. I sense that Neville’s view was that head knowing alone

will limit understanding of Cultural Keyline – understanding has to emerge

through the embodiment of values-based relevant experience.

My sense of ‘Cultural Keyline’ is that it is

of a matching form to the enabling interaction the Yeomans family had with all

of the myriad interlinking aspects of the soil, air, water, nutrient, and

warmth on their farms. Every aspect of the design and redesign of the Yeomans’

action on their farms was pervasively integrated. It was, to use Neville’s

phrase again, the ‘survival of the fitting’. Neville and his father knew that

it was virtually impossible to control a living system. Neville and his father

keenly attended to how the natural systems ‘worked’ on the farm and designed

their interventions to maximally fit with nature and allow nature’s emergent

properties to do what they do so well. P.A. and sons Neville and Allan (and

later, Neville’s younger brother Ken) would give the soil subtle enabling interventions

and perturbations, and then they would let the system self-organize towards

thriving.

Living systems have self-organization as an inherent property (for example, the

‘informal organization’ and the ‘grapevine’ in bureaucracies).

Neville

knew (June 1998) that living systems can reach a point, called in complexity

theory (Capra

1997, p. 167),

a bifurcation point, where there can be a sudden system negentropy (the

opposite of entropy) leading to the potential and emergence of sudden whole

system transcending transition to higher and more unpredictable complexity and

improved performance. The Yeomans had first-hand experience of how perturbation

and bifurcation work in nature in producing sudden whole system shift to a new

order of higher complexity (Capra

1997, p.28). The massive increase in detritivores in

their soil was one example. In the Fraser House context two examples of a

birfurcation point was firstly, when Neville went berserk in Big Group such

that the Unit survived well in his absence (Appendix 14), and secondly was when

Neville geared up the Frazer House community to support the 12 year old girl

(Appendix 15). In both cases Neville created a rich context where the Fraser

House social system jumped to a far richer mode of interacting. In each of

these cases Neville’s action was consistent with Pascale, Millemann and Gioja’s

(2000)

behavioural pattern in their book ‘Surfing the Edge of Chaos’:

Amplify

survival threats and foster disequilibrium to evoke fresh ideas and innovative

responses (2000, p. 28.)

Creating

contexts rich with potential for self-organising negentropy is very different

to laissez faire management where there is a hands-off approach.

Neville

applied these Keyline understandings in evolving Fraser House. In mirroring

Indigenous way, Fraser House was about fostering respectful co-existence and

meaningfully surviving well together. Everything Neville did in Fraser House

was designed to fit with everything else - naturally. Everything complemented and

supported other aspects. Things that did not work were fine-tuned or discarded.

Issues that arose in one context were resolved, or passed on to other contexts.

In Fraser House, what worked (as well as problematic aspects) was discussed

with everyone in Big Group. Issues not resolved in Big Group were passed on to

Small Groups and vice versa. Issues within Committees were resolved, or passed

on to Parliamentary Committee. Issues within the Parliamentary Committee were

reviewed by the Pilot Committee. This pervasive inter-connected weaving of

everything with everything is why Margaret Mead said it was the most

complete therapeutic community she had ever seen, and why Maxwell Jones

said that participants in Fraser House had to change.

Subsequent

to Neville’s death in May 2000, l identified four non-linear interconnected

inter-related aspects of Cultural Keyline:

1. Attending and sensing self organising,

emergence, and Keypoints conducive to coherence within social contexts

2. Forming cultural locality (people connecting

together connecting to place)

3. Strategic design and context-guided

perturbing of the social topography

4. Sensing and attending to the natural social

system self-organising in response to the perturbing and monitoring outcomes

Keyline is a model of sustainable

agriculture. Cultural Keyline is model for sustaining wellbeing based human

inter-acting and inter-relating. As Keyline fosters emergent farm potential,

Cultural Keyline is a rich way of fostering emergent and thriving potential in

social systems. A short summary of my findings relating to Neville’s Cultural

Keyline process in action follows. The following process is non-linear with

connexity between all of the following aspects. Some repetition reflects

fractal aspects, for example between sensing and designing.

Attending and Sensing

·

Attending

very closely to the features of the ‘social landscape’ in unfolding social

contexts

·

Being

open, surrendering and receiving all aspects of the social topography - sensing

the information, meanings and the issues in the forms, and not laying on it any

of our own projections

·

Sensing

each person, family, network and community as a self-organizing living system

·

Sensing

the connexity (interconnected interdependence) in the psycho-social topography

·

Sensing

the free energy and context role-specific functional behaviours in everyone

involved

·

Sensing

the information distributed throughout the system and recognising how this

information is concentrated and merges at the Keypoint – information about

mood, theme, value, interaction and unfolding outcomes - sensing their

inter-connectedness within the whole of what is happening.

·

Sensing

the fractal Cultural Keypoint(s) in the unfolding context - where these

energies and information (mood, theme, value and interaction) meet and

concentrate (just like the fractal quality of discrete information distributed

in each of the three land forms all meeting at the Keypoint), and have emergent

potential for social cohesion – and sensing the connecting theme(s) that

merge(s) from the concentrate – the theme(s) that has/have potent significance

for all in the unfolding context (whether participants realise it or not).

Forming Cultural Locality

·

Interacting

with the surrounding locality as a living system

·

Offering

to support people as a resource

·

Enabling

cultural locality – first the gathering, then the nexus towards community and

placemaking

·

Enabling

and fostering self-help and mutual-help

·

Enabling

others to tap into personal and interpersonal psychosocial and other resources

Strategic Design and Context-guided Perturbing of the Social

Topography

·

Unfolding contexts telling us what to do next

·

Enabling contexts where resonant people self organize in mutual

help

·

Fostering and enabling resonant grassroots networking in the

region

·

In

the unfolding context, sensing the inter-connectedness of mood, theme, value

and interaction; sensing the Keypoint where these meet and concentrate – and

sensing the connecting theme that merges from the distributed information

·

Engaging

in context appropriate perturbing at the Keypoint – from gentle to full on

perturbing - to evoke Keylines of interaction on the theme and associated mood,

values and interactions

·

Taking

the time and ensuring the sustaining of the Keypoint theme along the Keyline

till the turning point (potentially towards a new Keypoint theme), and then

recognizing and shifting to that Keypoint theme. If no Keypoint theme emerges,

then working with the free energy, or

·

Using

the Keylines of interaction as a guide to further engaging in action

Leaving Nature to do the Work

·

Sensing

and attending to the natural social system self-organising in response to the

perturbing

·

Honouring,

respecting, holding and leaving free the space and place for individual,

family-friendship networks and community re-constituting to happen

·

Having

faith in the thriving of living systems and knowing when to leave it to

self-organize and naturally do what it knows best - towards constituting/re-constituting

wellness

A

case study of Neville using Cultural Keyline is Appendix 14 (Going Berserk).

Neville

and his father were never into laissez faire management – having a non-involved

hands-off approach. When Neville travelled overseas he left in place a system

operating on the above four Cultural Keyline aspects. A group of people had

taken on his enabling role that entailed context specific tight control and

freedom and pervasive attending and sensing.

Neville

turned himself into a Keypoint. Metaphorically Neville placed himself in

society at the junction of three forms of social topography – the psychiatric

bureaucracy, the media, and the marginal fringe from the backwards of asylums

and no-parole prisoners. Within three years, Fraser House marginal residents

were training trainee psychiatrists in the new area of community psychiatry.

Neville became a zoologist, doctor, psychiatrist, sociologist, psychologist,

and barrister. Placing all this academic reflection within himself he placed

himself as head of the psychiatric study group associated with Fraser House. He

positioned the Study Group linked to Fraser House as the premier social

research facility in

My

understanding of the links between the farms and Fraser House are set out below:

No

one I interviewed for this research knew anything about Cultural Keyline;

Neville had never mentioned the term to them. While Neville never specifically

mentioned Cultural Keyline in any of his writings, the concept is implicit in

many of them; as an example, refer Appendix 4 – Neville’s forward to his

father’s book ‘

Cultural

Keyline themes implicit in Neville’s Forward:

·

Change

in values

·

Bio-social

survival depends upon harmonious working with nature

·

·

Landscape

must be husbanded with loving care

·

The

beauty and freedom of personal space depends upon caring for the integrity of

all our environment

Yeomans Farms Fraser

House

|

||

|

|

|

CULTURAL KEYLINE IN GROUPS

In

socio-morphological terms, a key role of the group facilitator was to

constantly scan for the ‘lay of the land’ in the group. This section extends

the above material on the use of themes as Keylines of discussion in Big Group.

A group of Fraser House patients wrote about how interest in themes was used in

groups – one version of this text included as Appendices 7 and 8 (Yeomans,

N. 1965a, Vol. 4, p. 17-20).

Big Group and Small Group themes emerged from the unfolding social topography in

the group. Themes were not concocted by group leaders and imposed. Themes are

where key issues for all in the group coalesce. Themes, as social coherence

amidst chaos, would arise from the context and often be self starting, or only

needing the slightest nudge to get underway. Once started on a coherence theme,

all participants tended to be hooked into their links to the theme.

Neville would place a metaphorical dam just below the Keypoint that would hold

the energy on the theme, and let the interaction move, as appropriate to

context, along the Keylines of discussion (metaphorically just downhill of the

contour as in Keyline ploughing) so that it moves with assistance of group

momentum (gravity).

Once

a theme was energised in Fraser House groups, and the theme was considered to

be not too superficial or inappropriate, the group may pay some attention to

it, and the suggested or emergent theme may be selected as ‘the Big Group

theme’ for an ensuing period during that hour. This theme would then not be changed

to another without good reason (Appendix 8). Interest in a theme may be viewed

as an attractor that determined the ‘flow’ of attention from ‘all directions’

near the ‘ridges of high potential energy’ to the ‘Keypoint’. Within Fraser

House Big and Small Groups, both interest and theme were emergent phenomena.

Interest (from the Latin: ‘to enter into the essence or God energy’) in

the theme becomes the Keypoint (literally and sociomorphically) for a time in

the Big Group social topography. The theme becomes the Keyline of discussion

for a time, and thematic psychosocial emotional energy in flow may be

transferred through the Big Group topography via ‘individual channels parallel

to the Keyline’ through the people topography. The word ‘theme’ is from the

Greek ‘thema’ meaning ‘motif; recurrent idea; topic of discussion or

re-presentation’.

The

following notes on interest in the theme is from the Fraser House Staff

Handbook (Appendix 7):

If

most of the group is involved in interaction, it goes without saying that they

are also interested. However, interest can be very high even though there is

not much interaction. Look at their faces, their feet, their hands, their

respiration, the way they sit, and it will be known if they are interested or

not (Yeomans,

N. 1965a, Vol. 4, p. 17-20).

The

Staff Handbook (Appendix 7) also notes the interaction between the

facilitator’s process and the theme, mood, interest, tension and the unfolding

interaction.

Resonance

between all attendees and the theme flowed from the theme having the inherent

property of being conducive to social coherence. To put this into context –

this was with a group of people who were the very mad and the very bad. The

group was filled with polarity – the under active and the over active, the

under controlled and the over controlled, as well as the under anxious and the

over anxious. There were colluding factions and unreachable isolates. In this

dysfunctional tangle there continually emerged themes that held everyone’s

interest – that everyone resonated with – that is, themes ‘conducive to

coherence’. Attendee resonance was supported by the theme-based connexity in

the cultural locality topography.

Group facilitators would specifically watch

for attempts to change the theme. In the patient’s write-up about the use of

interest in themes in Fraser House they wrote that attempts at changing the

theme:

……may be done deliberately by a patient for a

fairly obvious reason (such as a personality clash with someone involved in the

current theme), or a less obvious reason such as an unconscious identification

and a consequent wish to avoid the theme. It may also be done through plain

insensitivity on the part of the person making the attempt at the change. There

are many reasons for these moves, and it is the therapist’s role to decide on

the dynamics of the situations and then to make use of them by feeding them

straight back into the group at the time, and if necessary, to make an

interpretation of the dynamics operating in the events and occurrences’

(Appendix 7).

As more than one Keyline theme may be either

jostling for attention or potently latent in the ebb and flow of Big Group

energy, Neville’s skill was to identify the most potent one in the unfolding

context – perhaps the one that subsumes a number of the other presenting

Keypoint themes that then may become sub-themes as Keylines of engagement.

Neville passed on this skill to other Big Group facilitators and to me and

others who worked with him in action research.

Recall that there is only one Keypoint per

primary valley. Diagram 2 shows that Keypoint

in different primary valleys are often on different contours with different

potential energies in the respective valley systems. The Keyline only goes

along the contour through the Keypoint till the change of curve (refer diagram 2 in Chapter Five). Isomorphic with

Keyline, the next Cultural Keypoint theme may be at the same, or a higher or

lower contour and associated level of potential energy - so the group

facilitator would note this information in the social milieu in shifting themes

and work with the new energy. There were all manner of competences and nuances

associated with the shift of thematic keypoint in Fraser House groups and how

to work with the change in energy.

Peopling the

Topography – Sensing Cultural Keyline at the Keypoint

In 2006, I spoke with Terry Widders about

visiting Watsons Bay to sense Cultural Keyline at a Keypoint. Terry spoke of

‘peopling the topography’ and exploring the ‘contours of peoples’ minds’.

Taking up Terry’s suggestion I went to Watson’s Bay (refer Photo 24) with my

son Jamie.

Photo 4 Watson’s Bay Topography - compile made by me

from photos taken by tourist and sent to me October 2005 – used with permission

Recall Neville’s strategic use of locality

mentioned in Chapter Seven. Photo 2 reveals Watsons Bay’s topography. The

Watsons Bay Festival was in the park (The green area in the centre right of the

photo). The park is located in a primary valley below the main ridge and

between two primary ridges. The festival focal point was at a Keypoint in the

primary valley. The festival’s Keypoint theme was ‘celebrating life”. Neville

intentionally placed this celebration of life sixty metres below where

Sydneysiders go to suicide at The Gap. The bus in the photo is parked where the

Fraser House little red bus used to park two years earlier when the Fraser

House patients made crisis calls to stop suiciders.

Jamie and I came to Watsons Bay Park by ferry

and walked up to the Keypoint which is to the right of the path walking up.

Following Terry Widders suggestion, we decided to people the topography by

role-playing potent scenarios from our lives together. We did this while

standing at the Keypoint. In this we were modelling the position Neville took

when he was for instance leading Fraser House Big Group. Jamie and I separately

found where the different players in these re-enactments were located in the

Watsons Bay topography. When we compared where we sensed people were, we found

that we had complete agreement. For both us, our clarity about people’s

placement was inexplicable. Where we sensed them was definitely where they

were; people were definitely not in any other place in the surrounding

topography. Some were in the middle of the bottom of the valley. A few were

above us on the main ridge. Some were on one or other of the primary ridges.

Most were some distance from the Keypoint.

We sensed the themes that were conducive to

coherence in these people. We sensed the located people’s differing energy,

emotion and interest, and how these were linked to the Keypoint theme in the

scenarios. We sensed the nature of the interaction, mood and value mix that may

sustain interest and cohesion.

We also sensed the compaction in the social

topography, and how this compaction was sustaining fixed patterns of

dysfunction. We sensed the possible role-outs from perturbing the compaction,

from chisel ploughing the social terrain. We sensed the effect of this on

‘water’ flow as energy exchange. We sensed how this may flow gently through the

social system without eroding rush from the main ridge, and gently flow out

towards the primary ridges and be received throughout the system. We sensed the

effect of this dynamic on the unfolding of theme-based interaction. We noticed

how some people changed their positions as the scenarios unfolded, and the

effects of this change on the person and his/her interactions with self and

others. We then moved to the high point on the ridge (where photo 24 was taken)

to get another perspective. Neville would also do this to get the big picture.

We returned to the Keypoint and walked and sensed the Keyline. Then we

descended along one of the primary ridges to the bottom of the valley, sensing

the scenarios from the different locations, and as we placed ourselves on

others’ places.

I understand the above process has resonance

with Indigenous way. The richness of this embodied sensing of located

interactions only comes from doing it at a Keypoint and in and around the

topography.

SUMMARY

This

chapter has explored the many change processes evolved at Fraser House.

Neville’s adapting of Keyline to Cultural Keyline has been detailed. The next

chapter introduces criticisms of Fraser House and Neville, and includes a

response to these. The processes Neville used to spread Fraser House way into

the wider community and to phase out Fraser House are described. The chapter

concludes with a brief discussion of ethical issues in replicating Fraser

House.