Chapter Five - Connecting

Sustainable Agriculture

and Psychosocial Transition

ORIENTING

This

Chapter explores the research question, ‘What were the theoretical and action

precursors firstly, to Neville Yeomans evolving the therapeutic community

psychiatric unit Fraser House, and secondly, to the ways of being and acting

that Neville Yeomans used in his life work?’

Some aspects of Neville Yeomans’ way of

thinking, processing and acting are detailed, and their origins are firstly

traced to the innovative work that Neville did with his father Percival A.

Yeomans and brother Allan (and later with the younger brother Ken) in evolving

Keyline, a set of processes and practices for harvesting water and creating

sustainable agriculture. The chapter then details the influence on the Yeomans

of Australasia Oceania and East Asia Indigenous and grassroots ways.

INSPIRING TRAUMA

Neville’s

two traumatic incidents mentioned in Chapter One also had a profound, though

different impact on P.A. Yeomans, his father (Mulligan and Hill

2001, p. 193).

Neville’s father was, at the time Neville was lost, a mine assayer and a keen

observer of landscapes and landforms. His

father was

deeply impressed by the Aboriginal tracker’s profound knowledge of the minutiae

of his local land, such that, in that harsh dry rocky climate with compacted

soils, he could so readily follow the minute traces left as evidence of the

movements of a little boy. The other thing was that upon finding little

Neville, the tracker was so intimately connected to the local land and its

form, he knew exactly where to go to find water. It was not that this tracker

knew where a creek or a water hole was, as there was no surface water. He knew

how to find water whenever he wanted it, and wherever he was in his homeland.

He and his people ‘be long’ there (40,000 plus years). They were an

integral part of the land. They were never apart from it. The tracker and his

community saw the Earth as a loving Mother that provided well for them

continually (‘The Earth Loves us’ – from Neville’s Inma poem). The tracker was

‘of the land’. As soon as the tracker found Neville, he had to find the

right kind of spot for a short easy dig. Because of Neville’s dehydration, the

tracker needed water for Neville fast. He used his knowledge of his place and

quickly had Neville sipping water.

Mulligan

and Hill report that:

According

to Neville, it was probably this incident that gave his father his enduring

interest in the movement of water through Australian landscapes, because he

could see that an understanding of this would be a huge advantage for people

living in the driest inhabited continent on Earth (2001, p. 193).

In

the years after leaving mine assaying, P.A. Yeomans had moved on to having his

own earth-moving company. P. A. had just purchased the Nevallan and Yobarnie

properties in

WATER TELLING US WHAT TO DO WITH IT

P.

A. emulated the Aboriginal tracker in becoming familiar with the landform of

his two properties. P.A. wanted to store or use all of the water that landed

on the properties. In the Forties, P.A. wanted to be able to water his two

properties so they were so lush and green all year round, they would be

virtually fireproof. When the families acquired the properties the soil was

‘low grade’. It was undulating hill country with plenty of ridges that were

composed of low-fertility shale strewn with stones. The following photo taken

at Nevallan, one of the Yeomans’ farms, shows the original poor shale and rock

‘soil’ throughout the two properties when the properties were acquired.

Photo 1The low fertility shale

strewn with stones on P.A’s farm - from Plate 30 in

P.A.’s book ‘Challenge of Landscape’ – used with permission (Yeomans 1958b; Yeomans 1958a)

Photo 11 shows a

spade full of fertile soil after two years of the processes evolved by P.A. and

his sons. To clearly show the difference in the soil, a clump of the fertile

soil has been placed beside earth on the base of a tree stump that became

exposed when the tree fell over. This lighter low-grade soil had not been

involved in the processes the Yeoman’s evolved.

Photo 2 Fertile soil after two years compared to the original soil - a copy of Plate 30 in P.A.’s book

‘Challenge of Landscape’ - Used with permission

Within

three years, Yeomans and his sons had energized what conventional wisdom said

was impossible; they had altered the natural system so that the natural

emergent properties of the farm, as ‘living system’, created ten centimetres (4

inches) of lush dark fertile soil over most of the property. What is important

is that the local natural ecosystem did the work. P.A. enabled emergent aspects

in nature to self-organize towards increased fertility. With the interventions

that P.A. introduced, the property became lush and green twelve months of the

year. It was virtually fireproofed!

In 1974,

P. A described processes whereby 4 inches (10.16 cms) of deep fertile soil

could be created within three years (Yeomans

and Murray Valley Development League 1974).

The

balance of this chapter will specify the processes the Yeomans evolved and

applied on their farms and the Indigenous precursors they drew upon. It then

briefly introduces the ways Neville evolved in adapting his family’s farming

processes to psychosocial change.

Keyline

Emerges

Over

thousands of years, if this continent’s Aborigines wanted to spear fish in the shallow

creeks and rivers, they would copy the behaviour of the wading birds that wade

slowly, and then react extremely fast with their long beaks. The Aboriginal

hunter with his spear mimics these waders. Resonant with the continent’s

Indigenous ways, P.A. and his sons engaged in bio-mimicry - letting the water,

the landforms, the soil biota, and the balance of the local eco-system tell

them what to do. Neville told me (July 1998) that P.A. would take Neville and

Neville’s younger brother Allen out onto the farms as they were growing up

whenever it rained so they all could learn to see directly how the rain soaked

in at different times, how long before run-off would occur on different land

forms, and what paths down the slopes the run-off moved on different land

shapes. Like the Aborigines, they were learning to have all of their senses

focused in the here-and-now, attending to all that was happening in nature. As

action researchers, they became connoisseurs of their land and all life on it (Eisner 1991, p. 176). Whatever action P.A. and his sons did, they

always observed how nature responded.

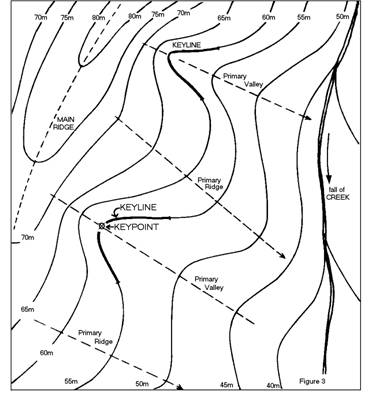

P. A.

obtained contour line maps with a useful scale of his property to further aid

his understanding of landform. According to Ken Yeomans in an October 2003

phone discussion, the map scale was typically 1 in 25,000 with 5 metre contours. Neville

said that his father constantly referred to the three primary landscape features - the

main ridge (elevated from the horizontal), the primary ridge (lateral to the

main ridge) and the primary valleys (lateral vertical cleavages). The farm was

perceived by P.A. as a cleavered unity, a feature pervasive in nature. P. A.

discovered where the best places were to store run-off water for maximum later

distribution using the free energy of gravity feed. It was high in a special

place in the primary valleys. Overflow from dams high in the primary valleys

were linked by gravity-based over-flow channels to lower dams.

Below is the most succinct statement I have

found written by P.A. Yeomans about what he called ‘Keyline’. I have extracted

it from P.A.’s speech at the UN Habitat ‘On Human Settlements’ Forum in

Keyline relates to a special feature of

topography namely, the break of slope that occurs in any primary valley.

Primary valleys are the highest series of valleys in every water catchment

region and lie on either side of a main or water divide ridge. They are widely

observed as the generally smooth or grassed over valleys of farming and grazing

land but are often overlooked and disguised in the city. On either side of the

primary valley is a primary ridge. Of the three basic shapes of land, namely,

main ridge, primary valley and primary ridge, the primary valley shape occupies

the smallest area of land and the primary ridge shape, the largest. In the

rural situation irrigation is a matter of watering the large primary ridge

shapes, even on land which appears flat.

All of the structures, processes and

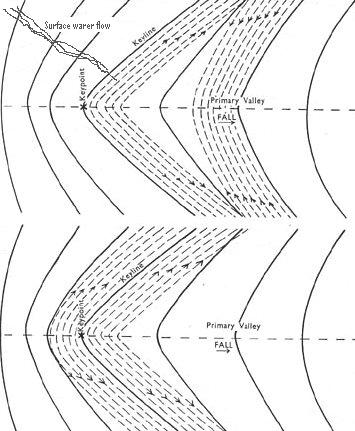

practices that P. A. Yeomans evolved he also called Keyline (Yeomans, P. A. 1971b; Yeomans, P. A. 1971a). Diagram 1

shows the main ridge (the dotted line along the left), two primary ridges (with

the arrows) and two primary valleys.

Diagram 1 – Photo from P.A.’s UN Habitat Speech (1976, p. 9)

Note that the Keypoint is on the fall line

on the contour above the first wider gap between the contours. The fall line is

marked on Diagram 1 above as the dotted line through the Keypoint. This wider

space between contours indicates less steepness on the slope.

Above the Keypoint is typically an

armchair-shaped land form that directs the water run-off so that most of it

ends up arriving in an area that may be as small as a square metre (the Keypoint)

– sometimes the very start of the typical creek as creek.

P.A. found that the optimal locations for

dams along the Keyline are where it crosses the drainage lines within primary valleys.

As stated, he called these the Keypoint for that primary valley.

P.A.’s

‘On Human Settlements’ Forum speech contains another description of Keyline:

It

will be observed that in the primary valleys the first slope falling from the

ridge above is short and steep – usually the steepest slope in the immediate

environs – while the second slope is flatter, much longer and extends to the

watercourse below. The point at which the change occurs between these two

slopes is named the Keypoint; the Keyline extends on the same level on either

side of this Keypoint and partly encloses a concave shape on the land. Only

primary valleys have Keylines (see contour diagram above) (Yeomans, P. A.

1971b; Yeomans, P. A. 1971a; 1976, p. 7-8).

Ken

Yeomans in a December 2005 email referred to the above quote:

I question the technical

accuracy of saying it ‘partially’ encloses a concave shape on the land.

Actually the Keyline occupies all of the concave shape of the contour line

curve. The change of direction of the contour from concave through the valley to the

convex curve of the ridge defines the end of the Keyline on

either side of each primary valley.

Diagram 1 above shows Ken Yeomans point

mentioned above - that the Keyline extends either side of the Keypoint for a

particular distance along the contour line running through the Keypoint.

P.A

then goes on to give a key point summary (1976, p. 9):

The

Keyline is significant because:

1. It is the first place in any valley where

rain run-off water, concentrated from the higher slopes, can form a stream.

2. It is also the first place where run-off

water disappears when the rain stops unless the water is contained.

3. It is the highest possible storage site in

any valley of the land.

4. It is often the highest point at which good

construction material for earth dams is available (higher up the earth may be less

decomposed and less suitable for dam building).

5. It is the essential starting point for a

water control system in any landscape that produces run-off; and

6. It is the line of change when the three

shapes of the land merge and readily disclose the geometry of land contours and

the behaviour of surface flowing waters.

The

Keyline is thus of major significance to any concept that aims to enrich the

environment by controlling and using all available water.

Note

point six above - the Keypoint in nature is saturated with information carrying

capacity. On this typically square metre of land is the junction of all three

land forms. Information distributed through each landform is present at the

Keypoint. The Keypoint, for those with eyes to see, is the place that reveals

the interaction of water with land. There is a confluence at the Keypoint of

all the water runoff from the main ridge and adjacent primary ridges down the

curved slope at the head of the primary valley.

Lincoln

and Guba made a similar point about distribution of information within a system

(quoted in Chapter Four):

Information

is distributed throughout the system rather than concentrated at specific

points. At each point information about the whole is contained in the part. Not

only can the entire reality be found in the part, but also the part can be

found in the whole. What is detected in any part must also characterize the

whole. Everything is interconnected (1985, p. 59).

The

Yeomans’ genius was that they spotted the information distributed throughout

the three landform systems and saw how the distributed information inter-connects

and interacts at the Keypoint. Keypoints are saturated with information that is

distributed in the system. Sensing and observing the Keypoint may reveal

insights as to how the whole complex dynamic system works.

Resonant with the above, Neuman also makes the observation that at

each point in a living system, information about

the whole is contained in the part (1997, p. 433).

Not only can the entire reality be found in the part, but also the part can be

found in the whole. What is detected in any part must also characterize the

whole. Everything is interconnected, inter-dependent, inter-related and

inter-woven.

Also

resonant with Yeomans and Neuman, Joseph Jaworski (1998, p. 80)

writes of a conversation with theoretical physicist Dr. David Bohm:

We

were talking about a radical, disorientating new view of reality which we

couldn’t ignore. We were talking about the awareness of the essential

inter-relatedness of all phenomena – physiological, social, and cultural. We

were talking about a systems view of life and a systems view of the universe.

Nothing could be understood in isolation, everything had to be seen as a part

of the unified whole.

Jaworski

writes of Bohm saying that it’s an abstraction to talk of nonliving matter:

Different

people are not separate, they are all enfolded into the whole, and they are all

a manifestation of the whole. It is only through an abstraction that they look

separate. Everything is included in everything else.

Yourself

is actually the whole of mankind. That’s the idea of implicate order – that

everything is enfolded in everything.

While

Jaworski and Bohm were talking about a ‘radical, disorientating new view of

reality’, this view has been the natural view of Australian Aborigines since

antiquity, and it was this view that the Yeoman’s used to perceive

inter-related things that Western farmers had never seen before. Barabasi (2003)

in his book ‘Linked - How Everything is Linked to Everything and What it Means’

also explores the same theme. Consistent with the foregoing, for the

Yeomans, the farm was a living system made up of interconnected, inter-related,

inter-dependent and interwoven living systems and associated inorganics. I have

been referring to this as ‘connexity’; this term was not used by Neville or the

other Yeomans, although it connotes their understanding of system linkages

well.

Where

the context around a Keypoint made it possible P.A. placed a dam wall so that

the dam could fill to that Keypoint. He designed his farms Nevallan and

Yobarnie to fit nature. All of the dams were placed so as to simultaneously get

water run-off, pass overflow to a dam below by gravity, and by gravity-based

irrigation, pass on the water to the soil when desired. Neville (August 1998)

and Allan (May 2002) both confirmed that they were with their father at the

moment when they recognized what he called the Keypoint and the Keyline in

landform – the central concepts in Keyline (Yeomans 1955a, p. 118). The very

spot where they realised the significance of the Keypoint is where the closest

water is in the closest dam in photo 12 below; the primary

ridges are on the left and right of the primary valley.

P.A.

wrote:

Once

the eye becomes trained to see these simple land shapes, and the mind has

selected and classified one or two, there is a fascination in the continuous

broadening of one’s understanding and appreciation of the landscape (1958, p.

56)

In

December 2005 Allan Yeomans told me that the special properties and

significance of Keypoints and Keylines as well as the associated design

principles such pattern cultivation, and placement of roads, fences and irrigation

channels were slowly realised over a number of years. Photo 14 below shows

strategic design of tree plantings as windbreaks and shade for livestock.

The Social Ecologist, Stuart

Hill and I visited Nevallan for the first time in 2001 and I took photo 15 below showing the place where P.A. and

Neville first spotted the Keypoint and Keyline. Like all Keypoints, the one in

the photo is on the drainage line. Photo 15

shows one of the primary ridges on the left near the top of the primary valley.

Photo 3 in Chapter One was taken looking up towards

where photo 15 taken.

Stuart

Hill, in Chapter Eight of his book on Australia’s Ecological Pioneers, outlines

some aspects of the process P. A. and his sons used (Mulligan and Hill

2001, p. 193):

What Yeomans senior discovered through

such patient observation was that there is a line across the slope of a

hillside where the water table is closest to the surface. The ground along this

line looks wettest and is reflective when it rains heavily.

Photo 3(Yeomans, A. 2005, p. 137) – Used with permission

Photo 4 down towards the Keypoint at the top of the dam.

It is the line along which it makes most

sense to locate the highest irrigation dams within the landscape, because this is

where the run-off water from above can most effectively be collected and

subsequently used at the most appropriate time to irrigate the more gently

sloping land below. Yeomans called this line the Keyline.

Yeomans first outlined his ideas about water

movement and how to detect Keypoints in a book entitled, ‘The Keyline Plan’ (1954). The books, ‘Challenge of Landscape’ (Yeomans 1958a), ‘Water for Every Farm’ (Yeomans, P. A. 1965), and ‘The City Forest’ (Yeomans, P. A. 1971a) followed. Three of P.A.

Yeomans’ books, ‘The Challenge of Landscape’ (Yeomans 1958b), ‘The Keyline Plan’ (Yeomans, P. A. 1955), and the ‘City Forest

: The Keyline Plan for the Human Environment Revolution’ (Yeomans, P. A. 1971b), including all of

their diagrams and photos, are now on-line on the Internet through the Soil and

Health Organization.

In

1993, Ken Yeomans, Neville’s younger brother published his book, ‘Water for

Every Farm: Yeoman’s Keyline Plant’ (Yeomans

and Yeomans 1993). This book clarified

some aspects of Keyline.

Alan Yeomans in a phone conversation

(December 2005) noted that the Keypoint and Keyline in successive primary

valleys along a ridge have an ascending (or descending) elevation as occurs in

Diagram 1 above. Allan spoke of regular patterns in nature; as an example, the Yeomans’

experience was that often the height of the bottom of a dam wall below a

keypoint in a primary valley been the height of the top of the dam wall in the

next lower primary valley (refer Diagram 1 above). This has implications for

linking the two dams by over-flow channel along a contour.

A

key aspect of Keyline was how the Yeomans changed the interaction between water

and soil. P. A. used chisel ploughing parallel to the Keyline, allowing the

natural self-organizing flow of water to run into these chiselled grooves. This

is not the same as contour ploughing as ploughing parallel to the Keyline soon

goes ‘off contour’ in a gentle downhill direction with an important effect.

This chisel ploughing results in shifting the direction of flow of surface water

around 85 degrees to flow down hill more slowly along the sides of the primary

ridges on each side of the primary valley. In contrast, contour ploughing has

the reverse effect, namely directing water towards the bottom of the primary

valley (from a phone conversation with Alan Yeomans Dec, 2005). Keyline

ploughing stops an eroding rush of surface water down to the valley floor,

slows the flow, spreads the soaking, and allows for a massive increase in the

moisture levels in the soil without water-logging. Consequently, water is

‘stored’ as it slowly filters through the soil, as well as being kept in all

the dams. The chisel plough that the Yeoman’s developed was called the Bunyip

Slipper Imp with Shakaerator (that is it shakes and aerates). This shaking action

reduces soil compaction. P. A. Yeomans won the Prince

Phillip Agricultural Design Award in 1974 for his design of this plough shown

in photo 16.

The

plough has the effect of placing a loose cap on a chisel groove so there is air

and space for water run-off to run along in the grooves underground. This cap

on the top of the groove minimises evaporation by sun and wind (Foster

2003). These changes to

the soil and water interaction are vital in the driest inhabited country in the

World. P. A. did not use ploughing that inverted the soil as he found that it

damaged soil ecology.

In

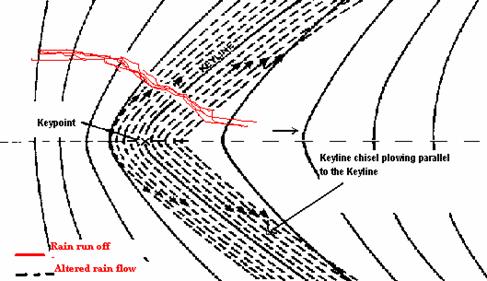

Diagram 2below, the red lines depict rainwater

run-off as it happens without the chisel ploughing. Once the run-off hits the

chisel ploughing it is turned around (approximately) 85% and runs out along the

ridges on both sides of the valley.

On the ridges, chisel

ploughing is carried out parallel to a selected contour line as depicted in

Diagram 4. Notice that the fall-line and the chisel grooves

are again at around 85 degrees to each other. This ploughing pattern on the

ridges also turns the rain or irrigation water flowing on the ridges from

running straight off the sides of the ridge. The chisel cuts have the water

again turned so that it runs at a much shallower slope along the side of

the ridge. This again slows the speed of run-off and allows the water to be

stored as it passes through the soil.

Creating Deep Soil Fast

There is fractal like repetition in nature

(Mandelbrot 1983) and in the Yeomans’ designs. Neville said that one of his

father’s design principles was ‘work with the free energy in the system’ (Dec

1993, July 1998). This was evident in the Yeomans use of gravity and the design

layout that maximized the capacity to use gravity. Another example of thriving

free energy is creating the context for the massive increase in detritivores

(worms and other organisms that break down detritus - decaying organic matter)

for generating new soil (discussed later).

P.A and Neville did not rest with the

notion prevailing in most quarters, that it can take up to 800 years to make

ten centimetres of soil by rock erosion and other breaking-down processes. They

asked how they could create ten centimetres or more of new topsoil in a few

years. They reasoned that soil could be created by constituting an

underground context/environment bringing together detritivores with ideal

combinations of air, moisture, seasonal warmth and a steady supply of organic

detritus (dead organic matter).

They knew that cropping a certain height

off grasses and plants just before flowering/seeding either by grazing or cutting

created a shock to the plant and a comparable size of dieback in root systems.

The energy that the plant had geared up for flowering and seeding is diverted

into rapid growth for survival. The roots that die create the organic material

for decomposing. What’s more, the dead organic root matter is already

spread underground through the soil where it is needed. The space previously

taken up by the roots become air chambers. The cut vegetation material was also

recycled into the soil. The plant responds with vigorous new growth that is

strategically irrigated. Keyline chisel ploughing and flood-flow irrigation

would increase soil moisture content and reduce compaction. This combination

supplied the conditions for a massive increase in detritivores (Yeomans, P. A. 1971b; Yeomans, P. A.

1971a; Yeomans and Murray Valley Development League 1974; Yeomans 1976).

Ten

centimetres of new topsoil was created in three years – something that

was previously thought to take around 800 years! Earthworms emerged in

abundance, the size of which (over 60 cm or 24 inches) had never been seen

before in the region. The Riverland Journal carried an article stating that H.

Schenk, head of the Farm Bureau of America described Nevallan earthworms as

being among the best he had seen. His words were, ‘Boy this must be the best

soil ever was’ (Yeomans

1956; Yeomans, P. A. 1971b; Yeomans, P. A. 1971a). Neville told me

(December 1993) he heard one well-travelled visitor saying that the only other

place he had seen comparable worms was in the fertile fields of the Nile delta

in

Thirty

years after P.A.'s death, the system he established on the farm still works by itself

with little maintenance required. As can be seen from Photo

18 below that I took in July 2001 when I walked the farm with Stuart

Hill, the farm still looks like sweeping gardens or a golf course. The

surrounding farms were covered with dry brown grass.

Photo 5

Photo 6 effect and the water harvesting achieved – Photo from P.A. Yeoman’s

book ‘City Forest Plate 1 – used with permission

Diagram 2 – adapted diagram from P. A. Yeomans’ book

‘Water for Every Farm’ (1965, p.

60) – used with permission

Diagram

3 Rain and irrigation water being turned towards or away from ridges – adapted diagram from P. A. Yeomans’ book ‘Challenge

of Landscape (1958b,

Chap 6, Fig. 5) – used with permission

In

Diagram 3 note that the contour lines above the Keyline are closer to each

other in the middle of the valley and get wider apart as they go towards the

primary ridges. Below the Keyline is the reverse pattern. The contour lines are

wider apart in the middle of the valley and get closer towards the primary

ridges. This difference in form gives the Keyline a property that no other

contour line has. Note that in the upper section of Diagram 3 contour

cultivation is parallel downward from a Keyline contour and the furrows track

water (the direction of surface water flow is depicted in top left of diagram

3) out towards the ridges. Note also that the second set of furrows upward from

a lower marked contour results in water flowing towards the centre of

the valley and that this would create the potential of erosion. Any ploughing

parallel to any contour above or below the Keyline in the valley has the

effect of tracking water towards the bottom of the valley rather than out

towards the ridges. The lower segment of

Diagram 3 shows the effect of Keyline cultivation working parallel to the

Keyline both up the slope and down the slope of the primary

valley. All of these furrows track water out along the ridges aiding the

slow passage of water through the farm. The arrows in both diagrams show the

downhill direction of the furrows.

Diagram 4 Keyline Ploughing Process

for Ridges - from P. A. Yeomans’ book

‘Water for Every Farm’ (Yeomans, P. A. 1965, p. 60) – used with permission.

In his 1971 ‘City Forest’ Book P. A.

acknowledges the seminal supporting role Neville played in the forming of his

ideas, ‘as psychiatrist and sociologist, for keeping me up to date on the

social and community implications’. He had Neville write the forward (Appendix

4) to this last book – The City Forest – about adapting his ideas to the design

and layout of a city (Yeomans, P. A. 1971b; Yeomans, P. A. 1971a).

Photo 7 at the left of the dam

Neville had evolved Fraser House back in 1959

when P. A. had Keyline well under way. Neville worked closely with his father

throughout Neville’s years at Fraser House and Fraser House outreach in the

years 1968 through 1971 when the City Forest Book was published. In the Forward

to the City Forest Neville sums up Keyline’s soil approach in these terms:

‘The soil which gives us life must be

developed in its own living processes so that it grows richer year by year

rather than poorer.’

In the

1970’s, Neville wrote a weekly column in the Now Newspaper (a Sydney suburban

paper) called ‘Yeomans Omens’ (Various

Newspaper Journalists 1959-1974). In this column he wrote that between 20,000

and 50,000 acres of Keyline forest could totally absorb and purify the liquid

effluent of

Photo 8The Header to Neville’s

Newspaper column in the Now Newspaper

The

Yeomans let nature tell them what to do. They always attended to nature and

respected the design in nature, and designed and redesigned their interventions

in a way that melded in with nature’s design, ‘design principles’ and emergent

properties (Capra 1997, p.28). The

Yeomans used ‘dynamic living systems’ as a strategic frame in their thinking,

design work and action. They also used bio-mimicry (mimicking nature) (Suzuki

and Dressel 2002, p. 66, 110) in their

designs. They engaged with all of the inherent aspects of the farm as a

holarchical living system (Holonic

Manufacturing Systems 2000). They

were ever aware that the ‘wholes’ in the living systems of the farms were made

up of parts, and these parts were themselves wholes made up of parts. The

Yeomans were very connected to this web of linkages.

After the Yeomans had introduced some changes to the soil

environment the massive changes were self-organizing. The soil, organic

matter, water and detritivores, as naturally occurring integrated systems, had

emergent qualities; that is, aspects started emerging, or coming into being,

which had not being present at lower levels of organization.

Designing

Farms

A

fundamental aspect of Keyline is that it involves design, and not just any

design; rather, a design guided by nature in the local place and context, such

that the resultant design superbly fits the local natural system.

Keyline insights and design principles guide

placement of paddocks, rows of trees as windbreaks and shade for stock (see

Photo 14), fences, gates, and roads. Landform and flood irrigation flow are

also taken into account in designing where paddock boundaries are placed.

Before P. A. and his

sons’ work, Australian (and other) farms had rarely been designed. They

tended to evolve in a haphazard or ‘traditional’ way – ‘this is the way we

always do it’. Farmers would impose their will on nature (‘dominion over’ in

the Jewish and Christian tradition). If something was ‘in the way’, farmers

would ‘bulldoze’ it out of the way.

In designing and using Keyline, things are

placed relative to other system parts and place for maximizing working well

with nature, functionality, emergence, inter-related fit, and use of free

energy in the system (for example, using gravity and the transformative energy

of the detritivores that break down organic matter). Neville

spoke to me (Dec 1993) of his father constantly fine-tuning things till they

would fit. Neville described this as ‘the survival of the fitting’. This is

discussed more fully in other places (Yeomans 1954; Yeomans, Percival. A. 1955;

Yeomans 1958b; Yeomans 1958a; Holmes 1960; Yeomans, P. A. 1965; Yeomans, P. A.

1971b; Yeomans, P. A. 1971a; Yeomans 1976; Yeomans and Yeomans 1993; Hill 2000;

Holmgren 2001; Yeomans 2001; The Development Of Narrow Tyned Plows 2002).

Neville’s

father made repeated use of ‘do the opposite’ type lateral thinking. For

example, P.A. experimented with putting a pipe through dam walls – something

conventional wisdom said was never done because of ‘inevitable’ wash out along

the outside of the pipe.

Neville’s

father solved this problem by putting baffles along the outside of the pipe.

Water running along the outside would carry with it small gravel and soil

particles that would be trapped by the baffles and fill in any gaps and compact

the soil around the outside of the pipe and therefore strengthen the seal

around it. All the Yeomans had to do was turn on the valve on the outside base

of the dam wall and they had gravity fed flowing water.

Diagram 5

marked by the square

So

far in this chapter we have summarised the Yeomans family’s evolving of Keyline

and discussed aspects of their farm designing and the way they worked with

nature to foster the self-organizing emergence of abundant fertility. The next

section explores some of the Indigenous origins of the Yeomans’ ways.

LINKS BETWEEN

SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE, PSYCHOSOCIAL CHANGE AND INDIGENOUS SOCIOMEDICINE

Indigenous influences on the Yeomans’ ways

will now be considered. Through P.A.’s

work in remote areas across the Top End of Australia and

For

Indigenous people living as nomadic hunter-gatherers on this continent, social

cohesion is a central component of healing and vice versa. The concept of

Indigenous ‘sociomedicine’ is implicit in psychiatrist Cawte's book, ‘Medicine

is the Law’ and other writings (Cawte

1974; 2001).

Neville

spoke (Dec 1993) about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living

traditional lives – for them, bush remedies for a wide range of troubles are

both widely known and widely used. This was confirmed by Geoff Guest (Aug

2004). However, if in these contexts sickness is deemed to have its source in social

trouble - if social cohesion is under threat - sociomedicine is used by

only a few law people who know the ways.

Neville understood the pervasive way

Aboriginal sociomedicine is linked into social cohesion.

The focus for healing or prevention is the whole group, and all become

involved (Cawte

1974; Cawte 2001).

Neville had firsthand experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

artistry - stories, sand drawings, rock paintings, songs and dances - and how

all are used to maintain social cohesion in being well together in community. Neville evolved his social action on his

understanding that for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, social

cohesion among one's people is paramount and isomorphic with the cooperative

inter-relationships found in nature.

Neville

and his father had been linked into these ways of thinking and experiencing

each other and the World. Through his life Neville had been accepted into

Yolgnu Aboriginal Communities living traditional lives in their homelands in

Arnhemland in the Australia Top End. Neville told me (July 1994), he had

experienced the storytelling and the singing and the corroborees. He had gone

hunting with them and participated in ancient ceremonies associated with a

person’s death, as well as other ceremonies. Neville said that these psycho-physical

and metaphysical experiences profoundly linked him into extremely rich

antiquities. Neville described these experiences as equalling any of the wisdom

literatures he had read, and certainly having the richness of the mythologies

of Grecian, Indian, Mayan and other cultures.

It is very easy to get lost in

the

Indigenous people constantly ‘absorb’ their land through all of

their senses. Being in their land has emotional tone; the land is in them and

they are in it, and of it. Neville acted from deep within this rich sensuous

emotional consciousness of connexity to and with land.

Neville

spoke of all manner of artistic expression and borrowing from nature being used

by Indigenous people of the Australasia Oceania Region to sustain and enhance

the social cohesion in their way of life. This artistic expression and social

action is called by some Indigenous people in the Region, especially those in

Vanuatu, ‘cultural action’, a term now being used throughout the Oceania

Australasia East Asia Region (CIDA 2002; Queensland Community Arts

Network 2002). Neville adapted this ‘cultural action’

into ‘cultural healing action’ (Yeomans and Spencer 1993). Neville described (December, 1993)

Cultural Healing Action to me as combining and embracing

the healing artistry of music making, percussion, singing, chanting, dancing,

reading poetry, storytelling, artistry, sculpting, puppetry, model making and

the like - and using any and all of these for increasing wellbeing. Neville was adept at using and enabling

Cultural Healing Action and he enabled me to gain competences in using it as

well.

Before,

during and after Fraser House, Neville had an increasing realization of the

resonance between Keyline, Cultural Keyline and Indigenous Self-Earth Mother

unity, and unity between and within all human and non-human life forms. All

of this experience was melded into the way

Neville and his father used in evolving their farms. As well, Neville’s

experience with Indigenous people had helped in the forming of his

way-of-being-in-the-world (Wolff 1976, p. 20) and social action in Fraser House and

beyond. Neville constantly engaged his way towards evolving

diverse social life worlds while enacting values that were based upon mutual

caring, loving respect between the sexes and the generations, peacefulness,

economic equity, social and political dignity and ecological balance (Yeomans

1974; Plumwood 1993; Plumwood 2002).

Neville

had firsthand experience of the destructive social fragmentation occurring in

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities; the aggression, the abuse of

women and children, alcoholism, destructive eating habits, high mortality rates,

criminal and psychiatric incarceration and the like. And yet for all this,

Neville saw in their traditional life-ways, processes that may have the potency

to have Indigenous peoples transform themselves towards being well, and

in addition, for this to be a model for fostering transition towards a humane

caring Global Epoch.

TIKOPIA - CELEBRATING DIFFERENCE TO MAINTAIN UNITY AND

WELLBEING

Inspired by the community feel of small

village life (Tönnies

and Loomis 1963),

Neville searched the anthropological and social psychological literature for

models of ‘community’ that were constituting and sustaining a way of life

(culture) based on social cohesion and well-being. He found that the Tikopians

were exemplars. It was the healing feel of the communal village life on Tikopia

depicted by Firth and its resonance with Neville’s notions of Cultural Keyline and his own childhood experiences

of Indigenous healing ways that so attracted Neville to use Tikopia as a model

for setting up Fraser House like a small Tikopia Village. None of staff and

residents I interviewed knew of this Tikopia connection except Margaret

Cockett; however,

Neville’s younger brother Ken’s first wife Stephanie Yeomans confirmed to me

personally in 2001 in Cairns that Neville regularly spoke to her about his

evolving Fraser House based on Tikopia lifeways. Stephanie was a psychiatric

nurse at

The Island of Tikopia

Firth

wrote that Tikopian community processes repeatedly involved

‘unifying-cleavage’. For example, they would engage in ceremonial distributions

of property, where the principle was that as far as possible, goods go to the

villages on the opposite side of the island - to those most different. There

would be periodic friendly inter-generational competitive assemblies among

those from differing villages, clans, and valleys. At these periodic friendly

competitive gatherings and assemblies among those differing from them, the

Tikopians would engage in competitive dancing, games and dart matches, as well

as share food and friendly fireside banter – what we have referred to as

‘cultural action’. An orchard of one clan group would be within the territory

of another clan group, bringing regular contact in day-to-day life. There were

multiple unifying links between valleys and across ridges.

According

to Firth (1957, p. 88):

Still

further are the cohesive factors of everyday operation, the use of a common

language, and the sharing of a common culture…

The

men from the East could only marry the women of the West. The opposite applied

to the men of the West. That is, people could only marry those most

different. The new brides would live with their husband’s family. As all land

was passed from mother to daughter, the couple would set up gardens on land

belonging to the wife’s mother (Matrilineal) - that is, on the opposite side to

where the couple were living. Each morning all the gardening couples from the

East would get up at sunrise, bath and have breakfast. They would then make the

climb through gaps in the volcanic ridge. They would also exchange news and

banter with couples going in the opposite direction before going to their

respective gardens. The process was reversed in the evening. The sun would set

first for those gardening in the East. So they would climb first and again meet

people going in the opposite direction. There would be more chatting, drumming

and dancing in the late afternoon light. As the tropical sun set in the West,

they would all return to their respective villages. There they would have

exchanges of vegetables for fish with the villagers who were the seafarers -

another different group to celebrate with. Often these beach exchanges were

occasions for more dancing and friendly play. After dinner, the interaction

would resume on the beach, or perhaps some would walk across the smaller ridges

to visit villagers in the neighbouring valleys.

Firth

made no comment throughout his book that the Tickopian communal village

life and mores may be helping to constitute and sustain individual and communal

psychosocial wellbeing. More importantly in the context of this thesis, Firth

makes no comment about the potential of the Tikopian’s way of life as a

practical working model for restoring psychosocial health and wellbeing in

dysfunctional people, families and communities. This possibility was recognized

by Neville.

Firth

discussed cohesiveness within the exploration of clan membership as one

framework for having an anthropological understanding of the Tikopians. Firth

uses notions of unity and cleavage in his book, ‘We the Tikopia’ (1957, p. 88):

A still further complicating factor is the

recognition of two social strata, chiefs and commoners, which provides a

measure of horizontal unity in the face of vertical cleavage

between clans and between districts. In former times there was even a feeling

that marriage should take place only within the appropriate clan. Important,

again are the intricate systems of reciprocal exchange spread like a network

over the whole community, binding people of different villages

and both sides of the island (the two major regions) in close alliance

(my italics).

OTHER INFLUENCES

During

Neville’s 1963 trip around the World he had exchanges with Indigenous people

about global epochal transition. Neville said that he tapped into a very

advanced discourse on global futures among Indigenous people around the globe.

An example of this discourse in action connecting land, sustainable agriculture,

water, food, and social wellbeing is the paper ‘Land Moves and Behaves’ (Zinck

and Barrera-Bassols 2005).

During

the 1970s Neville had studied spoken and written Chinese as well as Chinese

painting. Neville was familiar with and drew upon Confucian and Taoist thought

and way. Another resonant

Neville

told me (Dec 1993, July 1998) that he drew many understandings about society

from Talcot Parson’s writings and that these understanding influenced his

psychosocial approach. Neville had meetings with Talcot Parsons during his 1963

world trip and Neville said that these meetings further clarified Neville’s

frameworks linking Fraser House and cultural/societal transition.

MELDING

THE PRECURSORS

Neville,

in researching epochs and epoch making, knew that an epoch was a highly

significant keypoint – a turning point in human affairs. Neville (Dec, 1993)

made the connexion between his fathers ‘Keypoint’ and epochs being keypoints.

All of his father’s work was seminal in Neville’s epochal quest. Neville

recognised that in his father’s Keyline and the Indigenous wisdoms and lifeways

of the Region there were ways for energising a new cultural synthesis – and

Cultural Keyline could be a core process.

In

evolving micro-models of epochal transition Neville blended together Tikopian

community sustaining ways, Aboriginal and Islander social cohesion based

socio-medicine, and the design principles of Keyline.

SUMMARY

This

Chapter has traced the precursors of Neville Yeomans’ way of being-in-the-world

and the action research he used in his life work. It traced the evolving of

Neville’s way firstly, from the joint work he did with his father and brothers

Allan and Ken in evolving Keyline sustainable agriculture practice, and

secondly, from prior links that the Yeomans family had to Australasia Oceania

Indigenous way. Neville’s