Chapter Eleven - Fraser House Outreach

ORIENTATING

EXTENDING FRASER HOUSE WAY

Neville’s intention and outreach after

leaving Fraser House is neatly stated in his 1980 letter to the Therapeutic

Community Journal:

The Therapeutic Community model

has been extended into humanitarian mutual help for social change’ (1980b)

Recall that Maxwell Jones had written:

The psychiatric hospital can be seen as a

microcosm of society outside, and its social structure and culture can be

changed with relative ease, compared to the outside. For this reason

‘therapeutic communities’ to date have been largely confined to psychiatric

institutions. They represent a useful pilot run preliminary to the much more

difficult task of trying to establish a therapeutic community for psychiatric

purposes in society at large (1968, p. 86).

Having had his Fraser House experience, Neville

was commencing to do just what Jones had been intimating – establishing

therapeutic communities for psychiatric purposes in society at large. Neville began applying Cultural Keyline with the same

pervasively interwoven and ‘total’ pattern of action of Fraser House process in

many varied action research projects in the private sector. Neville created

many contexts where people were sharing experience and responsibility in

helping each other in evolving and sustaining social action research. In each context,

the social reconstituting potency of the ongoing action research was as

important, or more important than the outcomes. As in Fraser House, Neville’s

intention was to explore Cultural Keyline in action - community processes for

people embodying how to move towards being well together. The different

outreach actions were interconnected with each other, as well as with Fraser

House way. In each action Neville used all of the aspects of Cultural Keyline

mentioned above - in broad terms:

1.

Attending

and sensing and supporting self-organising, emergence, and Keypoints conducive

to coherence within social contexts – monitoring theme, mood, values and

interaction

2.

Forming

cultural locality (people connecting together connecting to place)

3.

Strategic,

design and emergent context-guided theme-based perturbing of the social

topography

4.

Sensing

and attending to the natural social system self-organising in response to the

perturbing, and monitoring outcomes

A framing theme in all of the

action research outreach was:

‘Exploring what works in community-based

reconstituting of society through humane caring community mutual-help action -

towards epochal change’.

Neville’s aims were:

1.

to explore re-constituting process among people on the margins

within the old cultural synthesis, and then

2.

to move as far away as he could to evolve a new cultural synthesis

- first Sydney, and then the Australia Top-End.

The ways in which Neville

extended Fraser House processes into the wider community include:

1)

Taking on advisory roles with peak bodies in health and other

areas – for legitimating and protecting action

2)

Taking Fraser House ways into the community by being

3)

Extending intercultural action research towards global change by

evolving links with many Asian and African community groups in

4)

Evolving (with others) festivals, gatherings and other happenings:

i)

ii)

The Paddington Festival, and from this, the evolving of Paddington

Bazaar (a community market) for ‘villaging’ his first mental health centre (in

Paddington)

iii)

iv)

Other community events

v)

Campbelltown Festival

vi)

Aquarius Festival

vii) ConFest (Conference Festival)

viii) Cooktown Arts Festival

5)

Forming the Keyline Trust to spread the word on Keyline

6)

Contributing suggestions which were adopted in divorce law reform,

and spreading the use of mediation

7)

Writing newspaper columns called ‘Keylines’ and ‘Yeomans Omens’

8)

Introducing Cultural Keyline implicitly to business and other

organisations

9)

Forming and evolving self-help groups

10) Becoming an election candidate

ADVISORY

ROLES

During the Sixties and early

Seventies, Neville was very active in many advisory roles in mainstream

organisations, including peak state and national bodies advising government. Neville

said (Aug 1999) that he was intentionally very active on advisory bodies at

this stage of his life in order to have, and sustain a very high public and

professional profile, and to legitimate, protect, and support Fraser House and

Fraser House outreach. This was the same reason he went out of his way to be

featured in a constant stream of newspaper and magazine articles (1965a; 1965b). These links helped ensure

Fraser House’s survival for as long as it did (discussions Neville, June-Oct,

1998; interview Cockett, April 1999).

Neville

advised a number of health organisations as well as organisations focusing on

softening drug and alcohol abuse, as well as Aboriginal Affairs and

criminology. Neville was the chairperson and founding director of a number of

them. For Example, Neville was a Member of the NSW State Clinicians Conference,

a founding director of the NSW Foundation for the Research and Treatment of

Alcoholism and Drug Dependency and a founding director of the national body of

the above organization, a member of the Committee of Classification of

Psychiatric Patterns of the National Health and Medical Research Council of

Australia and an advisor to the Research Committee of the New South Wales

College of General Practitioners (Yeomans,

N. 1965a, Vol. 12, p. 96).

Neville hinted to me (Aug 1998) that he had more than the twenty five advisory

roles listed in Appendix 24.

The extent of Neville’s advisory

work evidences firstly, the breadth of Neville’s acceptance in many spheres,

secondly, his acceptance at the highest level in these peak advisory bodies,

and thirdly, the breadth and inter-relatedness of his praxis.

COORDINATOR

OF COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

Despite

extensive enquiry, the best I could determine was that Neville finally left

Fraser House some time in 1968/9. He began extending the model of the Lane Cove

and Ryde Community Psychiatry Programs that he had energized prior to leaving

Fraser House. Neville focused his energies on extending the healing ways

evolved at Fraser House into ways of individual and communal self-help healing.

He and his personal assistant Margaret Cockett were extending the therapeutic

community option (as shown in Figures 1 and 3 in Chapter Ten) into the wider

community as dispersed (not all living together) urban therapeutic communities.

This was the precursor to the Laceweb as networked dispersed remote area

therapeutic communities and networks.

Prior to leaving

Fraser House, Neville had spoken continually of the need to create a new

section within the NSW Public Health System called Community Mental Health.

While still at Fraser House, Neville wrote a detailed monograph entitled, ‘The

Role of a Director of Community Mental Health (Yeomans, N. 1965x). This was a proposal, a ‘job

description’ and a ‘CV’ all rolled into one. His suggestion was adopted and

upon leaving Fraser House he became the coordinator of the New South Wales

Community Mental Health Services. Margaret Cockett characterizes Neville’s

leaving Fraser House as his being ‘promoted upstairs’ - because he was becoming

too well known, and also a threat to parts of the Health Department hierarchy.

Neville made ‘Margaret Cockett going with him

as his personal assistant’ a condition of his taking the position of the first

head of Community Mental Health; this was accepted. As an indication of the

lack of support for this new section within the Health Department, Neville and

Margaret were provided with an unfurnished room a couple of blocks down from

the main Health Department building. According to Margaret Cockett (August

1999), some evenings in the few weeks after Neville got this new position,

passers-by would have seen the two of them ‘spiriting’ ‘unwanted’ desks, filing

cabinets, chairs and other little needs to make their section a little more

functional. Neville and Margaret were finding it hard to get departmental

cooperation. Neville said (July, 1998) that his Fraser House detractors in the

health department were making things difficult for him in setting up Community

Mental Health.

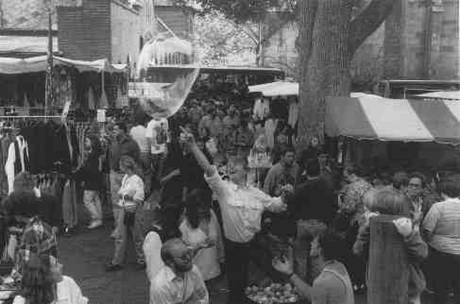

Neville set up

Photo

1. ‘Villaging’ the Church in

Paddington

– photo by M.Mangold - reproduced with permission

Neville’s suggestion was to surround the

Paddington Community Mental Health Centre and the Church with a Saturday community

bazaar. This was fully consistent with the Fraser House model of imbedding the

Unit within the local community, as well as inviting the community into Fraser

House.

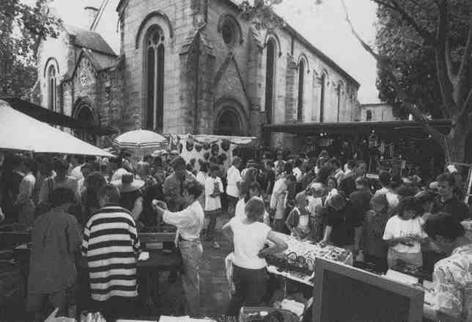

In Photo

31 the Vestry where Neville had his first Community Mental Health Centre is the

brick building on the left. The Church is on the right. Between and around both

buildings is where the Paddington Bazaar is held each Saturday morning. Adjacent the Vestry was a hall

Neville used for community meetings. This is where Neville and his friends

planned a series of Festivals (Mangold 1993, p. 4-11). Neville wanted to create the

public space of a small friendly village market reminiscent of Tikopia, where

everybody knows everybody and meets each other regularly. Neville wanted to

replicate the healing and integrative aspects of ‘small village life’ (Tönnies and Loomis 1963) of Fraser House around the

vestry in Paddington. The community mental health centre has long gone, though

Paddington Market survives to this day as a

Photo 2

Mangold’s photo of where Neville’s Community Mental Health Centre was

surrounded with community - reproduced with permission

The next section details Neville’s intercultural outreach.

Community Health

In 1968/69 there were moves to merge the Hospital’s Commission

that ran the

Neville and Margaret began linking with as many people as they

could that were initiating innovative action in the community towards health in

the widest sense. Margaret said (Sept 2004) that when Neville and Margaret went

looking for those broadening the views of community about ‘community’, very

prevalent among the community innovators were Fraser House ex-patients and

members of the Psychiatric Research Study Group. The late Sixties and early

Seventies were times when there was a great spirit of change in the community

and Neville and Margaret through their Fraser House action and momentum were

well placed to be catalysts energising and linking possibilities. One aspect of

this outreach by Neville and Margaret was forging links with the Asian and

African community in

EVOLVING

ASIAN LINKS

Neville’s interest in action towards epochal transition within

intercultural contexts is further evidenced by his extensive involvement in

cultural bodies during the late Sixties. He involved himself in the bodies

listed below in the following roles (Aug, 1998):

Senior Vice President Japan -

Councillor

Council member

Member:

Africa -

Australian Institute of

Internal Affairs

As

head of Community Mental Health, Neville and Margaret Cockett started community

based psychosocial groups. After sustained networking action by both of them,

they had a number of university students studying in

This involvement enabled Neville and Margaret to attend these

organizations’ joint and several activities and help them in forming/extending

mutual support networks among participants. Neville said he used this

interaction to refine what he called ‘intercultural enabler’ competencies and

sensitivities. Joining the

It was through the Asia Club that Neville met and married his second

wife Lien, a Vietnamese exchange student (Yeomans and Yeomans 2001). The photo below was taken from Lien’s book, ‘The Green Papaya’

with permission (Yeomans and Yeomans 2001).

Photo

3 Neville and Lien on their wedding day

on 27 November 1972 –

photo taken with permission from Lien’s book, ‘The Green Papaya’ (Yeomans

and Yeomans 2001)

SIDNEY

Neville was a founding member of

the Sydney Opera House Society formed in 1968 that worked to have the Danish designer

Jorn Utson complete the building. It was through this society that Neville met

Elias Duek-Cohen a town planner who would be involved in endeavouring to

further Nevilles father’s City Forest (Yeomans, P. A. 1971b)

processes in the Nineties.

Duek-Cohen explored the

implementation of P.A. Yeomans’ ‘

As an indication of the

‘positioning’ of the Sydney Opera House Society, as well as Neville other

committee people included:

Mr Gordon Samuels – QC, later

Judge, Chancellor of University of NSW, and Governor of NSW

Michael Baume - Top Diplomatic

post in

Peter Coleman - Premier of NSW

(From a copy of membership

application form posted to me by Elias Duek-Cohen)

WELLBEING

ACTION USING FESTIVALS, GATHERINGS AND OTHER HAPPENINGS

The Watsons Bay

The following section

uses the Watson’s Bay Festival as an example of Neville’s use of Festivals

towards new cultural syntheses. In the Sixties, Neville joined with Margaret

Cockett and others in forming, and becoming the president of the Total Care

Foundation, a registered charity. This entity was one of many formed by Neville

to replicate Fraser House community mutual help. This Total Care foundation was

used to evolve and hold the Watson’s Bay Festival in 1968 on

The process of exploring how people change as

they work together to change aspects of society was as important to Neville as

evolving and holding some event. Neville used the process of organizing festivals

and events in order to evolve networks and community. In the process of coming

together to put on the Watsons Bay Festival the participants were forming cultural locality (people connecting

together connecting to place. During Festival-based preparatory interacting

Neville was using Cultural Keyline - constantly attending and sensing and

supporting self-organising, emergence, and Keypoints conducive to coherence

within the festival generating contexts – monitoring theme, mood, values and

interaction. He would strategically perturb to foster emergence.

The

A planning

letter from Neville’s Total Care Foundation (Appendix 26) to the

Another letter

to the Town Hall in Sydney (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 12, p. 13) speaks of the Women’s’ Social Group, called

the Care Free Committee of the Total Care Foundation, helping with the evolving

of the Watson’s Bay Festival. This social group was another process for bonding

people together. Neville always gave some care to his naming of groups and

collectives. “Care Free’ has multiple meanings; ‘care-free’ as in ‘joyous’,

‘care provided free’ and ‘being free of care’. Having a women’s group was

consistent with cleavering into sub-groups at Fraser House. The letter states

that during the Festival there was an art exhibition at the Masonic Hall. One

Gallery alone lent $14,000 of paintings.

Neville timed

the Watson’s Bay Festival to coincide with the Sydney All Nations Waratah

Festival during 6-13 October 1968. This timing to coincide with a large

festival is a precursor to Neville’s evolving micro-gatherings as pre or post

gatherings to large global conferences in the Nineties, discussed later.

In keeping with

Neville’s intercultural synthesis focus, the Watson’s Bay Festival featured the

cultural artistry from twenty-three different countries (Appendix 25).

This is resonant

with lines from Neville’s poem about Inma (meaning Intercultural Normative

Model Areas):

It believes in the

coming-together, the inflow of alternative human energy, from all over the

world.

The

Second Festival – The Paddington Festival

To launch

Paddington Bazaar to surround his Paddington Community Mental Health Centre,

Neville worked with the local community in evolving the Paddington Festival.

Creating a community public place (cultural locality) – the Paddington Bazaar

was one of Neville’s themes in exploring community mutual help in energising

the Paddington Festival. It was held over the weekend of 21 - 22 June 1969. On

the Saturday there was a market bazaar in the main

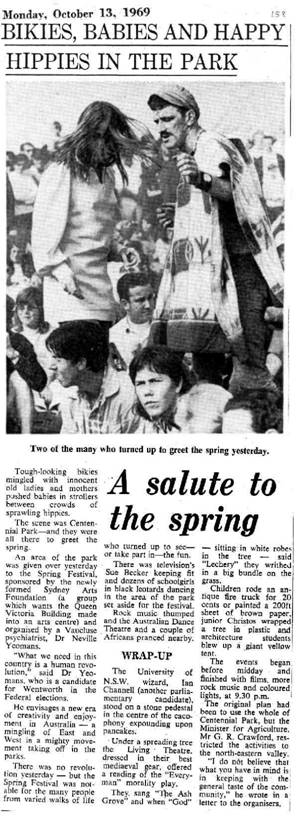

Festival Three - Centennial Park

The next Festival Neville and

others evolved was the Centennial Park Festival, a few kilometres from the

Sydney Central Business District. The Festival covered 540 acres in the

Neville was also a founding member

of the Sydney Arts Foundation. This Foundation was the organizer of the

Centennial Park Festival (Yeomans, N. 1965a, Vol. 12, p.

36). Again, for Neville, the shared

experience of foundation members working out how to get things happening

together was a central focus. The key aim of the Sydney Arts Foundation was to

establish an arts centre in Sydney (Yeomans, N.

1965a, Vol. 12, p. 36). The Centennial Park Festival was

supported by many Embassies, Consuls, civic groups, arts groups, national and

international societies and clubs and schools.

Neville’s inviting the support of many foreign embassies continued his

‘intercultural cooperating’ theme in events. He was also exploring the

strengthening of civil society based artistry. The range of events at the

Festival

Four - Campbelltown Festival

Neville, Lien, his younger brother Ken, and

Ken’s wife Stephanie were the key organizers of a small, though very important

Festival in 1971. It was held at another country property Neville’s father had

acquired off Wedderburn Road five kilometres from Cambelltown, which in turn is

around 50 kilometres down the main highway from Sydney towards Melbourne.

According to Bill Elliott (Sept, 2004) (a long term ConFest attendee – ConFest

is described shortly), as well as Ken and Stephanie Yeomans (Sept 2004), the

Cambelltown Festival was small, with around 150 attending.

Many of the cast and crew of the hit musical

‘Hair’ attended and added to the passion and artistry. Neville, Ken, and

Stephanie have all attested to the fact that there was a real fervour among the

attendees to mount a very large festival that would celebrate and engender

possibilities for a New Age – to quote the ‘Hair’ hit tune, a festival for the

‘Dawning of the Age of Aquarius’.

After the attendees had packed up the

Cambelltown Festival they held a meeting in an old shed near the Yeomans’

farmhouse where it was resolved to put on a festival and call it the Aquarius

Festival. They had a target figure of 15,000 people attending.

In their preliminary discussion

at Campbelltown about the proposed Aquarius Festival, they decided that they

wanted to work cooperatively with local people around the proposed Festival

site, have local people having a say in the Festival and sharing in any

profits, and preferably using the farm lands of more than one farmer. They also

wanted the whole process for evolving the Festival to be organic and natural –

to be self-organizing.

It is possible to see Neville’s Cultural

Keyline design principles being introduced by Neville as a theme and having an

influence on the decisions of this planning group. Note the implicit Cultural

Keyline principles:

1.

Enable and design contexts where resonant people self organize in

mutual help

2.

Have outside enablers work and network with the local people in

the region

3.

The local people have the say in meeting their own needs

4.

Support the local people in networking – (Festival on a number of

farms)

5.

Local people get flow-on (share in profits)

6.

The local action is self-organizing

Photo 4

Article and Photo on

At the Cambelltown

Festival meeting Ken Yeomans used his knowledge of Keyline to search maps of

Festival Five – The Aquarius Festival

The Aquarius

Festival did take place in Nimbin and 15,000 people did attend. It became the

first of the large alternative festivals in

The Festival did

make a profit and the local community decided that their share of the profits

be used to create a municipal swimming pool. This was agreed to, and Ken

Yeomans designed it using Keyline principles. The pool still functions well to

this day. It is round and has a sand base over concrete. It very gently slopes

in from the edges to become deep in the centre. The water flows up from below

in the centre, and flows out at the edges. The sand stays in place. The young

children enjoy the shallows. The Tuntable Falls Commune was started from some

of the Festival proceeds, and was designed on Keyline principles. That commune

continues to this day.

Festival Six – ConFest

When Jim Cairns,

Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister under Gough Whitlam, his personal assistant

Junie Morosi, David Ditchburn and others in the mid Seventies began preparing the

first ConFest - short for ‘conference-festival’, Jim Cairns and his group chose

to meet in the Church Hall next door to Neville’s Community Mental Health

Centre in Paddington (Mangold 1993).

Photo 5

Ken Yeomans – Photo from Ken Yeomans’ Web Site (Yeomans, K. 2005)

Neville and

others had energized a small urban commune focused around the Paddington

Community Mental Health Centre and the Bazaar. The Hall next to the Vestry had

become a regular

Photo 6

Photo by Michael Mangold - Used with permission. The Hall (next to the Vestry)

where the ConFest planning meetings were held

Neville attended the ConFest

planning meetings next door and contributed to the planning of the first

ConFest -

Walking

workshop/conferences were held on Keyline. ConFests have been held since the

Seventies. The Australian Down to Earth Network (ADTEN) was formed as an

administrative body and ADTEN subgroups formed throughout

Photo 7

Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns speaking at ConFest -

photo from DTE Archives

Following

encouragement by Neville to become involved in ConFest, I am one of around ten people

who select ConFest sites and energize the initial site layout and set up; a few

days before ConFest, site volunteer numbers swell to around 100. I have

surveyed 36 potential sites. Since 1992, I have regularly attended ConFest and

have been the one providing enabling support to the workshop process since

1994.

Between 150 and

300 workshops and events are held each ConFest on a very wide range of topics

relating to all aspects of the web of life consistent with Cultural Keyline.

Also consistent with Cultural Keyline, the ConFest workshop process is totally

self-organizing.

Photo 8 Photo

I took of ConFest Workshop Notice Boards all prepared for ConFestors to arrive

- December 2002

Photo 9 Villages

at ConFest

(photo from DTE archive)

With Neville’s

subtle orchestrating during the initial planning of the first ConFest, the site

set-up process for this Conference-Festival after twenty seven years is still

based upon the enabled self-organizing community and implicitly uses Keyline

and Cultural Keyline features. Nature guides design and layout. A few

volunteers with the way walk the site till it becomes familiar to them. The

land ‘tells’ the set-up crew where things can be well placed. Natural barriers

such as creek banks may mark the self-organizing edge of the car free camping

area.

The ConFest site is ‘organically’

set up. It is set up by voluntary action. No one is ‘in charge’ though there

are a few designated coordinators. Knowledge of what needs to be done and ways

to do the things are distributed among the volunteers. It is self-organizing.

It works. It is designed - roads are made, beaches created on creek or river,

showers and taps installed. There are hot tubs and steamrooms. Everyone attending

is asked to volunteer two hours during the ConFest. Site pack up takes around

two weeks and we hardly leave a trace that we have been there at all.

Consistent with Fraser House and

other action research contexts energised by Neville, only four people linked to

ConFest and the Down To Earth Cooperative that puts on ConFest have any

knowledge of Cultural Keyline, even though the site set up and pull down people

as well as ConFest itself generally follows Cultural Keyline way – some people

have embodied the way and can pass this on to others as lived experience. The

core group and the thousands who attend have embodied the Cultural Keyline

process without any understanding. Like Fraser House, ConFest is a

‘transitional community’; there are always enough people who already know the

ConFest way to induct first-timers into the ConFest Community experience.

ConFest does continually attract some mainstream people who want to manage,

direct, and control and these typically give up and leave, or adapt to the self

organising organic unfolding way.

Some feel for

the potency and mood of the first ConFest (at

Photo 10

ConFest sites are always chosen with special places –

photo from DTE’s archive

Festival Seven – The Cooktown Arts

Festival

Shortly after

the Aquarius Festival and the first ConFest in the Seventies, Jaciamo

Caffarelli a musician and painter (who was a Fraser House outpatient in 1961

who gave me permission to use his name) along with his wife Pamela were key

energizers of the Cooktown Arts Festival in Cooktown on Cape York, Far North

Queensland. Jaciamo had stayed in touch with Neville after Jaciamo ceased being

an outpatient. Coincidently, Jaciamo was living directly opposite Neville in

Yungaburra when Neville bought his house there in the Nineties. I spoke

extensively with Jaciamo and Pamela about the Cooktown Arts Festival and his

memories of Fraser House and Neville while I stayed with them at their place in

Yungaburra for a week and travelled with them to the Laura Aboriginal Festival

in June 2001.

At the time of

the Cooktown Arts Festival, Cooktown was an extremely remote outpost of about

350 people on

Photo 11

Photo I took of Jacaimo at Laura Festival

Given the

remoteness, the festival was very rich. Jaciamo told me (July 2001) that the

events included three three-act plays - complete with stage, scenery, costumes,

orchestra and lighting. One was a Chekhov play – The Cherry Orchard. A

puppeteer put on regular shows. As well, the Cairns Youth orchestra played

along with a number of swing and trad jazz bands, pop groups and a

xylophone/percussion group. Spontaneous acoustic music jamming sessions

abounded. Neville Yeomans, Jim Cairns (Deputy Prime Minister), and Bill

Mollison, one of the founders of permaculture, were speaker/workshop

presenters. There was a very active workshop scene on all aspects of wellbeing.

The next six

sections detail other outreach by Neville.

THE KEYLINE TRUST

As part of Neville’s adapting of Keyline to Cultural Keyline and

merging the two of them in his action research, Neville set up the Keyline Trust

with support from Ken and Stephanie Yeomans as well as Margaret Cockett and

others (Yeomans,

N. 1965a, Vol. 12, p. 44).

The Objects of the Trust were:

a) To produce and distribute documents, papers, photos, stickers,

films and other communications, cultural and artistic materials and productions

b) Such materials and productions to be Australian in origin and

dominantly for the purposes of enhancing community cooperation and mutual

support, locality, self respect, friendliness, creativity, culturally

appropriate peaceful nationalism and multinational regional cooperation

c) To assist other bodies with similar aims

The

middle object of the Trust, clause (b), is a succinct statement of Laceweb

action. Notice (i) the use of the term ‘locality’ in that clause - meaning

connexion to place and (ii) the implied ‘cultural locality’ at the local,

regional and global levels. In using the word ‘dominantly’ in the context of

the gentle purposes of the Trust, Neville is using the juxtapositioning of the

incongruous for provocative effect. The Trust

gatherings were another opportunity for Neville to explore community mutual

help, this time with a Keyline and implicit Cultural Keyline theme.

Neville

always took great care in wording documents. Neville was very interested in the

derivation and meaning of words. Often we would look up word meanings together.

Neville took the time to very carefully draft letters and other documents. We

often engaged in hundreds of hours on some documents. Examples are firstly the

‘Extegrity Document’ (Yeomans

and Spencer 1999)

discussed in Chapter Thirteen; we worked jointly on that for

ten months. A second example is the paper, ‘Governments and the Facilitating of

Grass Roots Action’ (Appendix 31) (Yeomans,

Widders et al. 1993a). That

paper was only six pages in length and three of us worked on it for nine weeks.

DIVORCE LAW

REFORM

Neville studied

law at the

Neville was a

key enabler in the development of the Divorce Law Reform Society of NSW.

Branches of the Society spread to other states. In the early Seventies Neville

prepared a series of submissions for the Divorce Law Reform Society,

particularly the desirability of setting up family and individual counselling

and family mediating processes. Neville told me (Aug 1998) that his writings

along with submissions from other members became a basis for submissions by the

Divorce Law Reform Society of NSW to Justices Evatt and Mitchell. These

submissions played a substantial part in the formation of the new Family Law

legislation.

Neville with

John Carlson wrote a monograph that researched the use of mediation in China

and other places as part of their law degree at the University of NSW (Carlson and Yeomans 1975). Mediation in the context of

what Neville called ‘mediation therapy’ is discussed in Chapters Twelve and

Thirteen. From these beginnings, the use of mediation has been growing in

Australian society. Neville told me (Dec 1993, Dec 1998) that

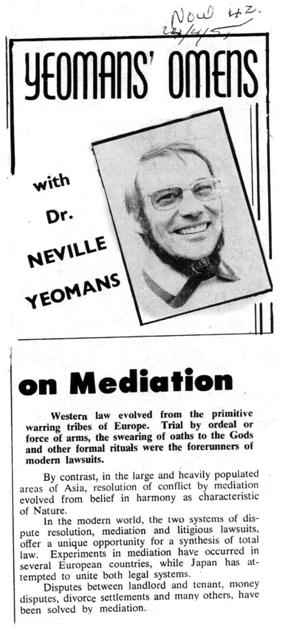

WRITING

NEWSPAPER COLUMNS

Neville edited a

regular weekly suburban newspaper column called Keylines. He used this to keep

before the Sydney readership, Keyline, Fraser House Way and the various

outreaches that he was energizing (Yeomans and Yeomans 1969) – refer photo 41 below.

The columns

always had themes consistent with Neville’s interwoven action and included

information about his father’s work being applied to creating city forests (Yeomans, P. A. 1971b), mediation and events Neville

was organising.

IMPLICITLY APPLYING CULTURAL

KEYLINE IN BUSINESS AND OTHER ORGANISATIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

Neville’s quest extended to fostering caring and being

humane in every aspect of life including work-life. During 1969 and the early

Seventies Neville held a regular small group in

In the late Eighties when I was consulting

in organizational change I was approached by the Federal Government’s

Department of Administrative Services about creating paradigm shift as well as

cultural change among their senior executive in Canberra. Neville and I wrote

on one page what he described as a global-local realplay as a resource for

senior executive change. When the Department decided to use American

consultants the department was not shown the Hypothetical Realplay. The

Realplay is included as Appendix 29. Consistent with Neville’s ‘On Global

Reform’ paper (1974) discussed in Chapters One and Thirteen, Neville set the hypothetical

realplay in an indefinite future time where there has been a shift in World

Order to regional governance, with local governance of local matters.

Photo

12 One

of Neville’s columns – Now Newspaper 24 April 1971

Neville had me prepare both

‘The Realplay’ (Appendix 29) and the ‘Rapid Creek Project’ (Appendix 37)

potentially for politicians in federal, state and local government, as well as

senior executive service people. Neville intentionally structured these

documents so they were both strange and novel, in order to act as a filter in

determining who we may be able to usefully engage with. In Neville’s view, only

those open and curious would engage. Deputy Prime Minister Brian Howe in the

Keating Government requested his head of the Federal Department of Local

Government to see me about the Rapid Creek Project (discussed in Chapter

Twelve) as that department was having difficulty in getting inter-sector cooperation.

I spoke with the Departmental Head in November 1993 who invited me (and

Neville) to link with people in their department and the Northern Territory

Government and Local Govenments in that Territory for possible consulting work.

At the time Neville and I where very busy and we did not take up this

invitation.

EVOLVING FUNCTIONAL MATRICES

In talking about

the connexity based energy-in-action in his various outreaches Neville used the

term ‘functional matrix’. Neville said (Nov, 1993) that he used this term to

refer to the ‘generative and formative developing and shaping of functions and

fields or foci of Laceweb action’.

Neville had

sustained Fraser House during 1959-1968 as tentative and transitional. He

resisted having anything he did being categorised and put into little boxes.

Creating all of his functional matrices allowed him to talk and act without

being pinned down to definitive specifics, which would in his view, limit and

distort.

The list of

Laceweb self-help and mutual-help functional matrices in Appendix 30, most of

them dating back to the late Sixties and early Seventies, is not exhaustive and

there is overlap between categories. Neville spoke of ‘matrix’ being from the

Greek word having the meanings listed below:

·

the womb

·

place of nurturing

·

a place where anything is generated or developed

·

the formative part from which a structure is produced

·

intercellular substance

·

a mould

·

type or die in which anything is cast or shaped

·

a multidimensional network

Neville was using

the word ‘matrix’ in all of the above senses. The word ‘functional’ was used to

convey that both the name of the entity and the social action involved had

related functions. Describing organizations as functional matrices was also

implying that Neville was not talking about top-down bureaucratic structures.

Neville said that he was talking about flat local-lateral networks by reference

to what they do rather than what they are. Neville used the terms

‘local-lateral’ and ‘loca-lateral’ in describing networks to denote that rather

than being bottom up or top down, local people were laterally networking

with other grassroots people. This networking may however have bottom up

influences. Like in the festivals, in each of these functional matrices, the

reconstituting potency of process was just as important or more important than

outcome. This mirrored the processes Neville used in all of his Fraser House

outreach.

Neville told me

(Dec 1993) that in talking about the Laceweb, people may refer to, for example,

the ‘Inma Nelps Lacewebs’. When they used the term ‘Inma Nelps Lacewebs’ no

specific organization in the usual sense was being referred to. Rather, it was

the function, field or focus of the action. Neville then drafted out for me the

names of many of the Laceweb Functional Matrices that he and others had evolved

since the late Sixties and what he termed their ‘function, fields and foci’ of

action (Appendix 30).

While typically

functional matrices were not formally organised, in 1969, Nexus Groups was registered

in NSW as a not-for-profit charity engaged in setting up self-help groups for

people with psychosocial stress. An abbreviated version of Nexus Groups’

constitution is attached as Appendix 32. The Total Care Foundation was another

registered charity evolved by Neville and others.

Nexus Groups

changed its name to ‘Connexion’ in the early Seventies and as one of its foci

of action became the publishing of the ‘Aboriginal Human Relations’ Magazine

(AHR) started by Dr. Ned Iceton in Armidale NSW

(Aboriginal Human Relations Newsletter Working Group

1971b). This Aboriginal Human

Relations Magazine reported on community healing action among Aborigines

throughout

Neville spoke

(Dec 1993, July 1998) of a person providing a chaplaincy role in Fraser House

who formed the self-help group that evolved into the organisation called Grow

which is now an international self help group assisting people recover from

mental dysfunction (Grow 2005).

Mingles was another of Neville’s functional matrices

dating back to the 1960’s. Mingles’ function was making it easier to form

friendships. It was one of a number of mutual wellbeing, support and

self-help/mutual-help networks/groups that emerged from Fraser House.

During September

1985 till late 1986 Neville, Chris Collingwood, Neville’s son David (and others

linked to that first workshop in Balmain during August 1985 where I first met

Neville) held regular experiential wellbeing sharing gatherings on the first

floor at 245 Broadway in

Celebrating and

re-creating

Community

wellbeing

Social

networking

Wellness

Enriching

families

Many of these

gatherings would also move for a time across the road into adjacent parklands

where we would engage in all manner of theme based sensory micro-experiences to

increase mind-body flexibility and choice – self and group trust and all-round

wellbeing.

Photo

13 A

photo I took in July 2001 of 245 Broadway in

Neville and this

same Mingles network energized a monthly event called Healing Sundays in Bondi

Junction in

It was

experiential, that is, simple healing ways that others have found to work were

tried out. No prior experience was necessary. Attendees could experience and

learn many healing ways. It was also a day for extending social and nurturing

networks. Some attendees were open to sharing their healing ways with the

gathering. Anyone who wanted to could link in with the enablers for the day and

arrange/enable a small segment - sharing with the group some healing ways.

Neville was the

key person in evolving and sustaining Healing Sundays. Neville stated

emphatically that he did not need to do this to discover process, as he had

done it a number of times before. He did it to give the core group of twenty

(and other attendees) the experience.

Notice again the

use of Cultural Keyline in the Healing Sunday:

1.

The

process encouraged every one to engage in attending and sensing and supporting

self-organising, emergence, and Keypoints conducive to coherence within social

contexts – sharing micro experiences while monitoring theme, mood, values and

interaction

2.

Forming

cultural locality (people connecting together connecting to place at Neville’s

home in Bondi Junction)

3.

Using

the emergent micro experiences for strategic design and context-guided

theme-based perturbing of the social topography

4.

Fostering

everyone’s sensing and attending to the natural social system self-organising

in response to the perturbing, and monitoring outcomes

Like creating a village to

surround Paddington Community Mental Health Centre, Neville would use Healing

Sunday to work with his psychiatric clients in a group context (by inviting one

to three to attend). One Healing Sunday attendee had been a patient of Fraser

House in the mid 1960’s. Neville would engage in strategic subtle and not so

subtle interventions during the Sundays (like unexpectedly telling me to work

with a patient of his in the group context when I alone knew she was furious

with Neville, and Neville had provoked the fury to prevent her suiciding

earlier that morning).

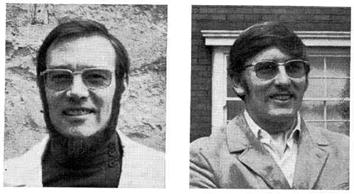

ON BECOMING AN ELECTION CANDIDATE

Neville and Ken Yeomans both entered as independent

candidates for the NSW electorates of Wentworth and Phillip respectively in the

1969 Federal election (Yeomans and Yeomans 1969). Both were against sitting

members and knew they had no chance. Neville, Ken and Ken’s wife Stephanie all

said that they were very active campaigners and used this as an opportunity to

raise the profile of all of the various themes that were dear to their hearts –

use of water, sustainable agriculture, community mental health, pollution,

intercultural harmony and the like.

Photo 14

Photos of Neville and Ken Used in Their Election Campaign from Neville’s Archives (Yeomans, N. 1965b)

Photo

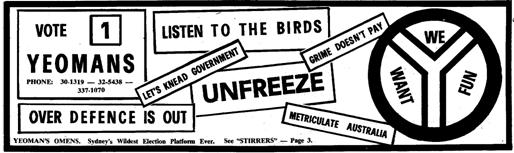

15

Advertisement in the Now Newspaper where Neville wrote a regular column (Yeomans,

N. 1965b)

As part of their election campaign, Neville

and Ken and Stephanie created an extensive set of humorous and creative bumper

stickers using a variety of fluorescent colours. These were called Licka

Stickas. Some are shown below.

INFLUENCING OTHER STATES

A casual conversation (July 2002) with a woman giving me a lift to

the airport in Hobart, Tasmania after some Laceweb gatherings there revealed

that she and many of her friends in Tasmania, especially in Hobart in the late

Sixties and early Seventies, closely followed Neville and Fraser House

developments. They used these as inspiration to push for all manner of changes

in that State’s Community and Family Affairs departments. She said that they

had many successes and that they evolved very effective wellbeing networks

throughout

Photo

16

Sample of Bumper Stikkers from the collection in Neville’s archives in the

Mitchell library (Yeomans,

N. 1965b).

FINDINGS

Neville’s

outreach was consistent with Cultural Keyline and demonstrated how ways evolved

in Fraser House, within a government funded professional service delivery model

could be interfaced with lay (non professional) self-help/mutual-help

networking that in turn could be self organising and self sustaining. This

further extends Neville’s biopsychosocial model and provides processes that may

be used in extending societal psychosocial resources as well as by the likes of

the Victoria Workcover Clinical Frame work. Neville’s outreach has demonstrated

ways in which new cultural syntheses may be fostered, and ways collapsed

societies may be reconstituted (in contrast to power-over pathologising (Pupavac 2005)). This is discussed further in Chapter 13.

SUMMARY

This chapter has documented Neville’s outreach from Fraser House

and detailed the links between Fraser House process and Fraser House outreach. In all of the various outreaches

from Fraser House, Neville blended seemingly disparate things into his action

research. He linked