CHAPTER THREE - BEYOND AND TRANSCENDING

LINKING SOCIO-PSYCHOBIOLOGICAL CHANGE

AND SUSTAIN-ABLE AGRICULTURE

WATER TELLING US WHAT TO DO WITH IT

P.A. YEOMANS AND ONGOING ACTION

Keyline’s Influence on Permaculture

Prophets

for Ecological Profit

ADAPTING KEYLINE TO CULTURAL KEYLINE

LINKS BETWEEN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE,

PSYCHOSOCIAL CHANGE AND INDIGENOUS SOCIOMEDICINE

TIKOPIA - CELEBRATING DIFFERENCE TO

MAINTAIN UNITY AND WELLBEING

A PSYCHIATRIC UNIT MODELED ON A SOUTH

PACIFIC ISLAND

ASSAGIOLI AND PSYCHO-SYNTHESIS

PHOTOS

Photo 1 This photo shows the low

fertility shale strewn with stones on

P.A’s farm

Photo 2 Fertile soil after two

years compared to the original soil

Photo 3 After three years the

property looked like a plush rural golf course.

Photo 5 At Nevallan

in July 2001, looking down towards the Keypoint at the top of the dam

Photo 6 A Different

Angle Showing the Ridges at the top of the Primary Valley

Photo 8 Notice the

chisel ‘terracing’ effect

Photo 9 Advertisement for Chisel Plow – Bunyip Slipper Imp with Shakaerator’

Photo 10 One of the

overflow channels - photo taken June 2001

Photo 11 The Gentle

slope of the overflow channel coming away from the near corner of the left dam

Photo 12 Channel

leading from one dam wall to the dam below – July 2001.

Photo 13 Irrigation

channel for flow irrigation.

Photo 14 Irrigation

flag in place.

Photo 15 Flag

diverting water to flood-flow over adjacent land.

Photo 17 Neville at

Keyline field day leaning on the shovel

Photo 19 Nevallan in

2002 looking back to the Keypoint

Photo 20 The Header to Neville’s

Newspaper column in the Now Newspaper

Photo 21 Parting of

the Ways - Laura Festival in 2001.

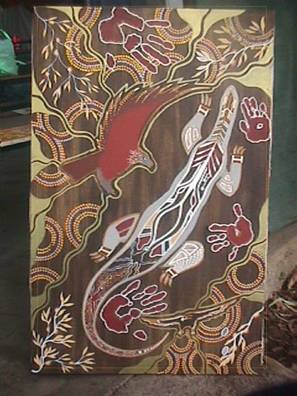

Photo 22 Tracy’s

Painting Relating to Social Cohesion

Photo 23 Embodying Crocodile Ways

DIAGRAMS

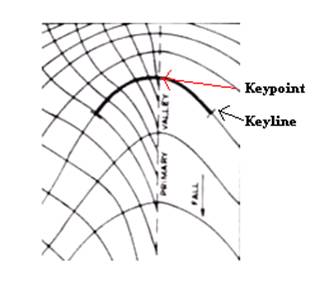

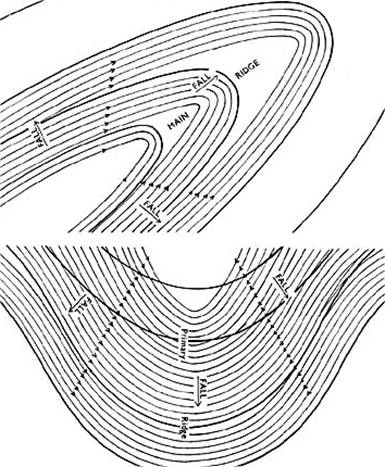

Diagram 1 The

Keypoint - Where Convex Curve Becomes Concave

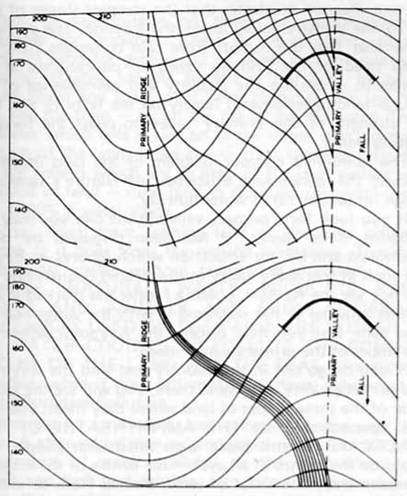

Diagram 2 The

Keypoint and Keyline

Diagram 3 ‘S’ Shaped

Curve of Surface Water Runoff and the Curve of the Keyline

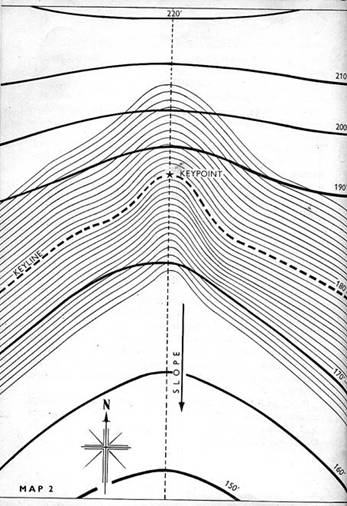

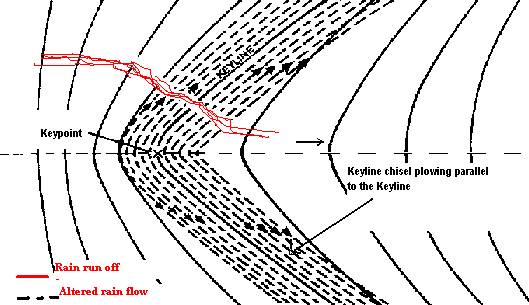

Diagram 4 Plowing

parallel to the Keyline

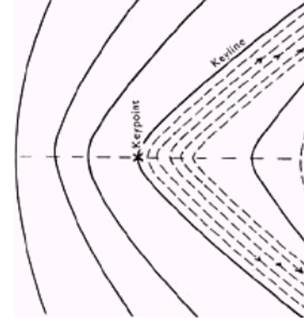

Diagram 5 Chisel

Plowing Parallel to the Keyline with arrows direction of changed run-off flow

Diagram 6 Rain and

irrigation water being turned out along both ridges

Diagram 7 Keyline

Plowing Process for Ridges.

DRAWINGS

Drawing 1 Drawing by

L. Spencer of the Island of Tikopia

LINKING SOCIO-PSYCHOBIOLOGICAL CHANGE

AND SUSTAIN-ABLE AGRICULTURE

This Chapter explores the research question, ‘What, were the

precursors and nature of the Ways of being and acting that Neville Yeomans use

in his life work? This Chapter encapsulates some aspects of Neville Yeomans’ Way of

thinking, processing and acting, and traces its origins to the innovative work

that Neville did with his father Percival A. Yeomans and brother Allan in

evolving Keyline, a set of processes and practices for harvesting water and

creating sustainable agricultural practice.

The Chapter outlines the

precursors of, and stimulus for Keyline in Australiasia Oceania Region

indigenous people’s profound connexion and familiarity with, and knowledge of

their land. The modeling and adaptation by Neville of socio-healing and

sociomedicine ways of indigenous people of the Region is outlined, including

how Indigenous ways were combined with Cultural Keyline in forming Fraser

House.

The potency of place and

public space, and its link with social cohesion and therapeutic community is

introduced. Psycho-synthesis, Taoism and other precursors and influences are

briefly discussed. Neville’s adaptation of Keyline to ‘Cultural Keyline’ in

evolving Fraser House is introduced.

INSPIRING TRAUMA

In 1993 while I was staying with Neville in Yungaburra he talked

about how the two traumatic incidents - being lost as a three year old and

being caught in the fire - had had such a profound impact on him. These two

traumatic incidents had also had a profound, though different impact on his

father (Mulligan and Hill 2001).

P. A Yeomans was, at the time Neville was lost, a mine assayer,

and a keen observer of landscapes and landforms. P. A. Yeomans was

deeply impressed by the local knowledge of the Aboriginal tracker who found

three year old Neville. P. A. had been impressed by the Aboriginal tracker’s

profound knowledge of the minutia of his local land, such that, in that harsh

dry rocky climate with compacted soils he could so readily follow the minute

traces left as evidence of the movements of a little boy. The other thing was

that upon finding little Neville, the tracker was so intimately connected to

the local land and its forms he knew exactly where to go to find water. The

tracker was ‘of the land’. He and his people ‘be long’ there

(40,000 plus years). They were an integral part of the land. They were

never apart from it. It was not that this tracker knew where a creek

was, as there wasn’t one. The tracker and his community saw the Earth as a

loving Mother that provided well for them continually. He knew how to find water whenever he

wanted it and wherever he was in his homeland. As soon as the tracker

found Neville he had to find the right kind of spot for a short easy dig. Because of Neville’s dehydration, the tracker

needed water for Neville fast. He quickly had Neville sipping water. Hill

reports that, ‘according to Neville, it was probably this incident that gave

his father his enduring interest in the movement of water through Australian

landscapes, because he could see that an understanding of this would be a huge

advantage for people living in the driest inhabited continent on Earth (Mulligan and Hill 2001)’.

Just as Neville had also been profoundly influenced by his Uncle’s

death in the grass fire, P.A was also profoundly influenced (and traumatized)

by the same incident. During the ensuing years after leaving mine assaying,

P.A. had moved on to having his own substantial earth moving company. P.A had

acquired the farms to take advantage of tax breaks then available. P. A. had

just purchased the properties with his brother-in-law Jim Barnes the year

before the fire. Recall that Jim Barnes died in the fire. After the fire, P.A.

had to decide whether he would keep the farms and run them alone. He decided to

stay on the farms. These points were confirmed by Neville, Allan, Ken, and

Stephanie Yeomans.

WATER TELLING US WHAT TO DO WITH IT

P. A. emulated the Aboriginal tracker in becoming familiar –

family – with the landforms of his two properties. P.A. wanted to store or use all of the water that landed on the

properties. The massive restrictions the authorities now have on building farm

dams and controls on irrigation in large parts of Australia were not in place

then. In a 2002 conversation, Neville’s youngest brother Ken said that no dams

can be now made in the Murray Darling Basin, and farmers in this area have

limited say as to the storage and use of the rain that falls on their own

properties.

P.A. wanted to be able to water his two properties so they were so

lush and green all year round that they would be virtually fireproof. When the

families acquired the properties the soil was ‘low grade’. It was undulating

hill country with plenty of ridges that were composed of low fertility shale

strewn with stones. The following photo taken at Nevallan one of the Yeomans’

farms shows the original poor shale and rock ‘soil’ that was right throughout

the two properties when P. A. and his brother-in-law Jim Barnes bought them.

Photo 1 This photo shows the low fertility shale

strewn with stones on P.A’s farm

The next photo shows a spade full of fertile soil after two years

of the processes evolved by P.A and his sons. To clearly show the difference in

the soil, a clump of the fertile soil has been placed beside earth on the base

of a tree stump that became exposed when the tree fell over. This lighter

low-grade soil had not being involved in the processes the Yeoman’s evolved.

Photo 2 Fertile soil after two years compared to

the original soil

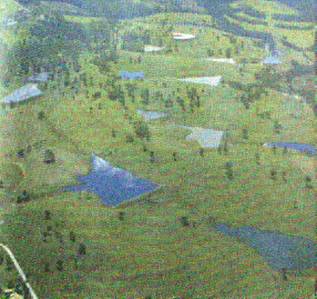

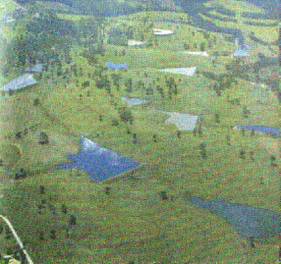

Within three years Yeomans and his sons had energized what

conventional wisdom said was impossible. They had altered the natural system so

that the natural emergent properties of the farm, as ‘living system’,

created ten centimeters (4 inches) of lush dark fertile soil over most

of the property! What is important is that in the Ways they used, the local natural

ecosystem did the work. P.A. enabled emergent aspects in nature to self

organize towards increased fertility. ‘Emergent’ is a name for a system

aspect that is present at some level of organization and not present at lesser

levels of organization. For example, the sweetness of glucose is not present in

any of the molecular building blocks of glucose (Internet Source 2002).

The processes the Yeomans used to foster natural emergence is

discussed in the following section. With the interventions that P.A.

introduced, the property had become lush and green twelve months of the year. It was

virtually fireproofed! The photo below shows the plush farm that emerged in

three years.

Photo 3 After three years the property looked like a plush rural

golf course.

In 1974, P. A described processes whereby 150 cms (five feet)

of deep fertile soil could be created within three years (Yeomans and Murray Valley Development League 1974). These processes are detailed later.

Neville’s profound insight was to see how the processes that

created such vibrant fertility on the farm could be applied in the psychosocial

life world. This Neville set out to do as his life work. The balance of this

Chapter will specify the processes the Yeomans evolved and applied on their

farms and the indigenous influences involved. It then introduces the ways

Neville evolved to adapt his family’s farming processes to psychosocial change.

Keyline Emerges

Over thousands of years, if this continent’s Aboriginals wanted to

spear fish in the shallow creeks and rivers, they would copy behavior of the

wading birds – they wade slowly and react extremely fast with their long beaks.

The Aboriginal hunter with his spear mimics these waders. Resonant with the

continent’s indigenous ways, P.A. and his sons engaged in bio- mimicry -

letting the water, the land-forms, the soil biota and the balance of the local

eco-system tell them what to do. P.A. would take Neville and Neville’s younger

brother Allen out onto the farms as they were growing up whenever it rained so

they all could learn to see directly how the rain soaked in at different times,

how long before run-off would occur on different land forms, and what paths

down the slopes the run-off moved on different land shapes. Like the

Aborigines, they were learning to have all of their senses focused in the

here-and-now, attending to all that was happening in nature. Whatever action

P.A. and his sons did, they always observed how nature responded. P. A.

obtained contour line maps (with a useful scale) of his property to further aid

his understanding of landform. Neville said that his father constantly referred

to the three

primary landscape features - the ridge (elevated from the horizontal), the

primary valley (vertical cleavages) and the secondary valleys (lateral vertical

cleavages). The farm was perceived by P.A. as a cleavered unity, a feature

pervasive in nature. The concept ‘cleavered unity’ is discussed further below in relation to the Solomon Islander

Tikopia people (Firth 1957) and Neville’s therapeutic community Fraser House. P. A. discovered where the best places were to store run-off water

for maximum later distribution using the free energy of gravity feed. It was

high in a special place in the primary valleys. Below is a photo showing the

water harvesting P. A. achieved. Overflow from dams high in the primary valleys

were linked by gravity-based over-flow channels to lower dams.

Photo 4 Nevallan farm dams

The whole farm layout was designed to

fit nature. All of the dams were placed so as to simultaneously get water run-off,

pass overflow to a dam below by gravity, or by gravity based irrigation, pass

on the water to the soil when desired.’ P.A. writes that Neville was with him

out on the farm at the very moment when P.A. recognized what he called the

Keypoint and the Keyline in landform – the central concepts in Keyline.

Photo

5 At Nevallan in July 2001, looking down towards the

Keypoint at the top of the dam

Photo 6 A Different Angle Showing the Ridges at the top of the

Primary Valley

Photo 7 This view looks up towards the ridge at the top of the

primary valley from where Photos 5 and 6 were taken

The Keypoint and Keyline have special

properties and significance. Stuart Hill and I visited Nevallan for the first

time in 2001 and took the above photo showing the spot where P.A. and Neville

first spotted the Keypoint and Keyline. The Keypoint is right at the nearest

end of the closest dam. Like all Keypoints the one in the photo is on the

drainage line where the convex curve of the hill becomes concave.

Diagram 1 The Keypoint - Where Convex Curve

Becomes Concave

The Keyline extends either side of the Keypoint for a particular

distance along the contour line running through the Keypoint. Stuart Hill, in chapter

eight of his book on Australia’s Ecological Pioneers, outlines some aspects of

the process P. A. and his son’s used (Mulligan and Hill 2001):

‘What Yeomans senior discovered through such patient observation

was that there is a line across the slope of a hillside where the water table

is closest to the surface. The ground along this line looks wettest and is

reflective when it rains heavily. This

is the line where the slope changes from being convex above to concave below.

It is the line along which it makes most sense to locate the

highest irrigation dams within the landscape, because this is where the run-off

water from above can most effectively be collected and subsequently used at the

most appropriate time to irrigate the more gently sloping land below. Yeomans called this line the Keyline.’

Above the Keypoint is typically a land shape that directs the

water run-off so that most of it ends up arriving in an area of about a square

metre (the Keypoint) – the very start of the typical creek as creek. P.A. found

that the optimal locations for dams along the Keyline are where it crosses the

drainage lines within primary valleys. As stated, he called these the Keypoint

for that primary valley.

Yeomans first outlined his ideas about water movement and how to

detect Keypoints in a book entitled, ‘The Keyline Plan’ in 1954 (Yeomans 1954). The books, ‘Challenge of Landscape’, ‘Water for Every Farm’, and

‘The City Forest’ followed (Yeomans 1958; Yeomans 1958; Yeomans 1965; Yeomans 1965; Yeomans

1971; Yeomans 1971). Three of P.A.

Yeomans’ books, the ‘Keyline Plan’ ‘The Challenge of Landscape’ and the ‘City

Forest: The Keyline Plan for the Human Environment Revolution’ including all of

their diagrams and photos are now on-line through the Soil and Health

Organization (Yeomans 1958a; Yeomans 1965a; Yeomans

1971a). P.A’s youngest son Ken also wrote on Keyline (Yeomans and Yeomans 1993) as well as Holmes (Holmes 1960). All of the structures, processes and

practices that P. A. Yeomans evolved he also called Keyline (Yeomans 1971; Yeomans 1971).

Notice the Keyline design

features adapting natural place-forms in the above three photos. The closest

dam is sited so it is in the highest point in the valley floor where the convex

curve shifts to being concave.

P. A, used chisel plowing

parallel to the Keyline allowing the natural self-organizing flow of water to

run into these chiseled grooves. This resulted in shifting the direction of

flow of surface water around 85 degrees towards the ridges. This stops an

eroding rush of surface water down to the valley floor, slows the flow, spreads

the soaking, and allows for a massive increase in the moisture levels in the

soil without water-logging – that is, water is ‘stored’ as it slowly filters

through the soil as well as been kept in all the dams. These changes are vital

in the driest inhabited country in the World. P. A. did not use plowing that

turned the soil as he found that it damaged soil ecology.

Photo 8 Notice the chisel ‘terracing’ effect

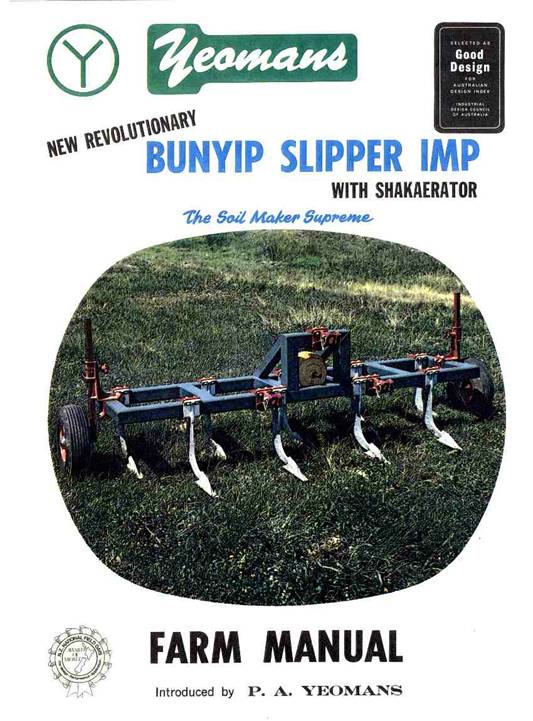

P.A. adapted a chisel

plough from USA that cut grooves into the farms low-grade compacted soil by

adding a shaking vibration which created small underground hollow channels

around ten centimeters or four inches blow the surface, adjustable depending on

depth of ‘top soil’. P. A. won the Prince Phillip Agricultural Design Award in

1974 for his design of this, ‘Chisel Plow with Shakaerator’ (2002). Neville also was very familiar with his fathers and

brother Allan’s engineering designs for farm equipment. One was the Slipper Imp

an advance on the chisel plow they had been using (Yeomans 1974).

Photo 9 Advertisement for Chisel Plow –

Bunyip Slipper Imp with Shakaerator’

Notice that they describe the plow as

the ‘soil maker supreme’. The ‘Shakaerator’

name implied a shaking action that broke up compacted soil and aided aeration.

Diagram 2 is a contour map of the top of a primary valley. The dark curve is

the Keyline. The Keypoint is on the primary valley drainage line. The upside

down parabolic curves are the contour lines.

Diagram 2 The Keypoint and Keyline

Note that the top four contour lines

are relatively close together indicating a steep concave fall. The distance

between the Keyline contour and the one below is considerably wider indicating

a flattening out of the fall. The contour on the top of the first widest gap

between contours at the top of the primary valley is the spot that the convex

slope becomes concave. The ‘S’ shaped lines indicate the flow of over ground

water runoff for the left-hand side of the valley looking uphill. This S shape flow can be confirmed by drawing short lines at right

angles to a series of contour lines (the flow direction at that point) at the

head of a valley and then linking up these lines. Note that the water runs at right

angles to each successive contour and this sets up the ‘S’ shape flow. Diagram

3 shows the land surrounding Diagram 2. The lower repeated image shows a

segment of the flow of run-off water.

Diagram 3 ‘S’ Shaped Curve of Surface Water

Runoff and the Curve of the Keyline

Diagram 4. shows Keyline chisel

plowing parallel to the Keyline. Note that by plowing parallel to the Keyline

the grooves soon go off contour.

.

Diagram 4 Plowing parallel to the Keyline

Keyline plowing is not the same as

contour plowing. By creating the chisel grooves parallel to the Keyline as

depicted in Diagrams 4 and 5 the water run-off that was coming down the slope

in an S shaped curve is turned about 85 degrees to run out along the sides of the

ridges in the chiseled grooves.

Diagram 5 Chisel Plowing Parallel to the

Keyline with arrows direction of changed run-off flow

In Diagram 6 the red lines depict

rainwater run-off as it happens without the chisel plowing. Once the run off

hits the chisel plowing it is turned around 85% and runs out along the ridges

on both sides of the valley.

Diagram 6 Rain and irrigation water being

turned out along both ridges

On the ridges, chisel plowing is carried out parallel to a

selected contour line as depicted in Diagram 7.

Diagram 7 Keyline Plowing Process for Ridges.

Notice that the fall-line

and the chisel grooves are again at around 85 degrees to each other. This plowing pattern also turns the water

from running off the sides of the ridge, typically in ‘S’ shaped curves to the floor of valleys. The chisel cuts have the

water again turned so that it runs at a much shallower slope along the side of the ridge. This again slows the

speed of run-off and allows the water to be stored as it passes through the

soill.

The

Placing of the Dams

When P. A. was in outback mining areas he had noted the way the

Chinese would build long mining water-races along contours (where they placed

their dams). These enabled the Chinese miners to move water a long way, often

with a fall along the water-race of only a few centimeters. In some places in

Australia where P.A. Yeomans traveled in his mine assaying work, Chinese miners

had ample water, whereas in the same area, farmers would have no dams and no

water. P.A. well knew that similar principles had been used by the Romans and

others in making aqueducts. How P.A. adapted the water-race/aqueduct ideas into

Keyline is discussed below.

All the Yeomans’ dam walls

have a specially designed and constructed pipe that comes out at the base of

the middle of the dam wall. The pipe is fitted with a valve on it on the

downhill side. No pumps are needed. Water from the valve feeds into irrigation

channels. Other dams are situated so that overflow from a higher dam can flow

out an over-flow channel by gravity down into the lower dam(s). The overflows

are gentle so no erosion occurs. When the dam level drops the overflow channel is

self-seeded with grasses. When I walked the Nevallan property in June 2001, the

overflow channels, about 15 feet across, were covered with lush green grass and

they had had no maintenance for 20 years! Photo 10 is the overflow channel for

the closest dam shown in photos 5, 6 and 7. Stuart Hill is standing on the top

of the dam wall that curves away to his right. A car could be driven across the

wall easily.

Photo 10 One of the overflow channels - photo

taken June 2001

Photo 11 The Gentle slope of the overflow channel coming away from

the near corner of the left dam

Photo 12 below shows the

channel allowing excess water from one dam to flow gently down to a lower dam.

The photo was taken from three quarters of the way down the dam wall. Photo 12

was taken from the dam wall of the closest dam shown in photos 5, 6 and 7

facing towards the far dam in those photos.

Photo 12 Channel leading from one dam wall to

the dam below – July 2001.

The irrigation channels

are filled from the valve outlet by gravity flow. The irrigation channel is

sited below the overflow channels.

Photo 13 Irrigation channel for flow

irrigation.

Water flowing along an irrigation

channel was delivered to a stretch of land by placing an irrigation ‘flag’

across the channel. This was usually made from a three-square meter piece of

material with a pipe through a hem across one end. This pipe was laid across

the channel and the material lay in the channel to make a temporary ‘wall’.

Photo 14 Irrigation flag in place.

Photo 15 Flag diverting water to flood-flow

over adjacent land.

Designing

Farms

The above considerations

guided placement of paddocks, fences, gates, and roads. Landform and flood

irrigation flow is also taken into account in designing where paddock

boundaries are placed. Up to P. A. and his sons’

work, Australian (and other) farms had rarely been designed. They tended to evolve in a haphazard or ‘traditional’ way – ‘this

is the way we always do it’. Farmers would impose their will on nature

(‘dominion over’ in the Jewish and Christian tradition). If something was ‘in

the way’, they would ‘bulldoze’ it out of the way. In designing and using

Keyline, things are placed relative to other system parts and place for

maximizing functionality, emergence, inter-related fit and use of free energy

in the system. This is discussed more fully in other places (Yeomans 1954; Yeomans

1955; Yeomans 1958; Yeomans 1958; Holmes 1960; Yeomans 1965; Yeomans 1965;

Yeomans 1971; Yeomans 1971; Yeomans 1976; Yeomans 1993; Yeomans and Yeomans

1993; Yeomans and Yeomans 1993; Hill 2000; Holmgren 2001; Yeomans 2001; 2002).

A central thing about Keyline is that it involves design, and not

just any design; rather, a local context based design that superbly fits

the local natural system. Nature told them what to do. The Yeomans

always attended to nature and respected the design in nature, and designed and

redesigned their interventions in a way that melded in with nature’s design,

‘design principles’ and emergent properties (Capra 1997, p.28). The Yeomans thought like dynamic living systems and used

bio-mimicry (Suzuki and Dressel 2002, p. 66, 110) in their designs. They engaged with all of the inherent aspects

of the farm as a holarchical living system (Holonic Manufacturing Systems 2000). They were ever aware that the ‘wholes’ in the living systems of

the farms were made up of parts, and these parts were themselves wholes made up

of parts. And the initial whole referred to, was itself a part of something

bigger. P.A. and Neville were very linked to this web of linkages. For them,

the farm was a living system made up of interconnected, inter-related,

inter-dependent and interwoven living systems and associated networked

inorganics (a connexity relating). ‘Connexity’ is a central lived, embodied,

and experienced framing concept. My definition of ‘connexity’ is as follows:

‘Connexity’

embodies the notion that everything within and between natural contexts and

everything within and between people and context (culturally and

inter-culturally) is inter-dependent, inter-related, inter-connected,

inter-linked and interwoven – whether we recognize it or not.

Keyline has many design

features, all resonant with natural

system connexity. ‘Connexity’ was to my knowledge

a term not used by Neville although it connotes his understanding of system

linkages well. ‘Connexity’ is a resonant concept in understanding Neville’s Way

and the praxis he enabled. The Yeomans linked into the connexity in their

farms’ ecosystem strategically. They, as living systems, were linked into the

farm living systems. They used nature as their guide as what to do, and what to

do next. Everything that they did was consistent with these design principles.

There is fractal like repetition in nature (Mandelbrot 1983) and in the Yeomans’

designs. One design principle was ‘work with the free energy in the system’.

This was evident in the Yeomans use of gravity and the design layout that

maximized the capacity to use gravity. Another example of thriving free energy

is creating the context for the massive increase in detritivores. This is

discussed in the next section. As an illustration of fractals, Allan suggested

taking a map of the Amazonian River system and reducing it in size. If we keep

reducing it, it looks exactly like a smaller river system. If we keep reducing

it looks exactly like a small river system. If we reduce it smaller, it looks

like a creek system. If we reduce it even small it may well be a creek with its

small tributary system.

Another design and intervention principle was that if there were

an impasse, they would tend to maximize possibilities for provoking the system

to self-organize towards functional adaptation to bypass the impasse. This was

linked to looking for the free energy in the system. They would work with what

works near, surrounding, associated, and connected to the impasse rather than

the impasse itself. An example was how to introduce an outlet pipe through the

base of the middle of the dam without water seepage along the outside of the

pipe causing a washout of the dam wall. The conventional wisdom of the day was

that you never put a pipe through a dam wall. The Keyline literature discusses

how they designed out the impasse by working with nature rather than against

nature, such that nature compacted the soil around the pipe. Self-organizing

processes in nature eliminated seepage in association with the aspects they

designed into the pipe and the pipe installing process.

Another design principle was, in deBono’s terms, to use all of the

different kinds of thinking (de Bono 1999). One of these divergent forms of thinking was to explore the

potential in doing what was the opposite, or most different to what people

always do. As an example, on a summer

morning in 1993 in Yungaburra, Neville and I were about to fold a very large

tarp covered in water and leaves from the mango tree. I started to straighten

it out by folding it in like I always

do when Neville said, ‘Let’s do what my father would do. Do the opposite. We

can fold it out, not in. Each time we grab from the middle and walk the middle

to the side. Doing this we will fold out so most of the leaves and water will

run off rather than being trapped in the folded tarp. If we fold water in it

will be so heavy, we wont be able to shift it!’ We did this folding out rather

than folding in. It was simple and it worked. That tarp was one of several used

in the small Laceweb campout in the rainforest in Kuranda discussed in Chapter

Nine.

Creating

Deep Soil Fast

The wider thinking behind this water-soil changework was that P.A

and Neville did not rest with the notion prevailing in most quarters, that it

can take up to 800 years to make ten centimeters of soil by rock erosion and

other breaking-down processes. They asked how they could create ten centimeters

or more of new topsoil in a few years?

They reasoned that soil could be created by constituting an underground

context/environment bringing together detritivores (creatures that live on dead

organic matter) with ideal combinations of air, moisture and a steady supply of

organic detritus (dead organic matter).

They knew that cropping a certain height off grasses and plants

just before flowering/seeding either by grazing or cutting created a shock to

the plant and a comparable size of dieback in root systems. The energy that the

plant had geared up for flowering and seeding is diverted into rapid growth for

survival. The roots that die create the organic material for decomposing.

What’s more, the dead organic root matter is already evenly spread underground through the soil where it is

needed. The space previously taken up by the root becomes air chambers. The cut

vegetation material was also recycled into the soil. The plant responds with

vigourous new growth that is strategically irrigated. Keyline chisel plowing

and flood-flow irrigation would increase soil moisture content. This

combination supplied the conditions for a massive increase in

detritivores (Yeomans 1971; Yeomans 1971; Yeomans and Murray Valley Development

League 1974; Yeomans 1976).

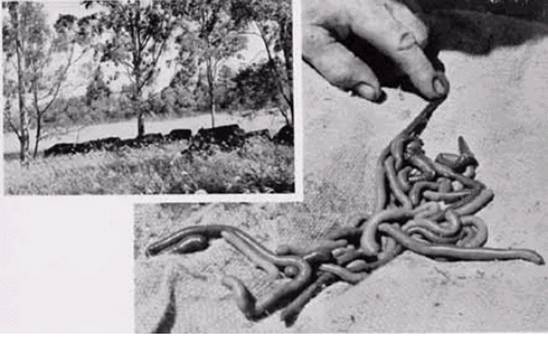

The changes

P.A. and his sons made to the farm created a context where natural emergent

processes in nature made a quantum self-organizing expansion in thriving

populations of soil producing detritivores and other biota and

related aspects that massively increased the farms fertility and output.

Ten centimeters of new topsoil was created in three years – something that was previously thought to take around 800 years! Earthworms emerged in

abundance, the size of which (over 60 cm or 24 inches) had never been seen before in the Region. The Riverland Journal carried

an article stating that H. Schenk, head of the Farm Bureau of America Bureau

Movement described Nevallan earthworms as among the best he had seen. His words

were, ‘Boy this must be the best soil ever was’ (Yeomans 1956). Neville told me he heard one well-traveled visitor saying that

the only other place he had seen comparable worms was in the fertile fields of

the Nile delta in Egypt.

Other

aspects of the Way

Before he acquired the farms P.A. had had a business in removing

mine overburden. This experience also served him well in tackling the

substantial earthworks in making farm dams, some of them very large. The

largest surface area dam P.A. built on his own farms was at his Kencarley

property in Orange, NSW. The largest by volume was at one of his first two

farms, Nevallan in Richmond. The Kencarley dam covered 43 acres and had a dam

wall over 10 meters high. P.A. suspected this wall may not hold as the soil

that it was made from was far from ideal. He had checked that if the dam failed

it would not jeopardize other people’s life or property. He was prepared to go

ahead and construct the dam and if it failed he could still learn from the

experience. Allan Yoemans told me that when the dam was filled, water did begin

seeping through in parts. P.A. had devised ways of repairing dam walls by

having controlled explosions under water. This is a classic example of, ‘do the

opposite! One may think that you would never blow up a failing dam wall. P.A.

had worked out a way to use these explosions to consolidate and compact the

soil. He had had success with this method before. However, this time it did not

save the dam and small tunnels formed in the sandy soil. After the water had

all drained away, P.A. was able to examine the areas where the explosives had

gone off and better understand the effect.

Outcomes

of the Yeomans Way

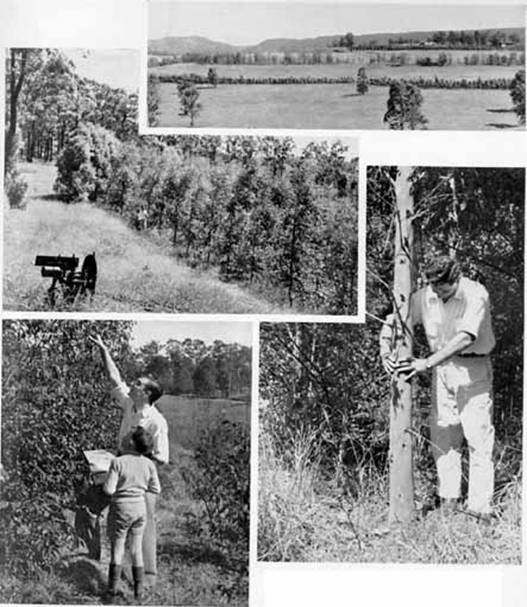

The picture on the left in Photo 16 shows the lush growth on what

had been very low-grade pastures. The other picture shows the worms mentioned

previously.

Photo 16 Keyline outcomes.

P.A. attracted distinguished guests to the two properties. In

Photo 17 Dr.

Neville Yeomans is shown second from the right (leaning on the shovel). The

photograph includes the following people (from the left):

His Excellency, the Governor-General

of Australia, Field-Marshall Sir William Slim, G.C.B., G.C.N.G., G.C.U.L.,

G.B.E., D.S.O., M.C., is welcomed to "Nevallan". Left to right:

Professor McMillan, Neville’s father (P. A Yeomans), Neville’s brother (Allan

J. Yeomans), Mr. C. R. McKerihan, C.B.E., His Excellency, the Governor-General,

Dr. Neville Yeomans, and Mr. John Darling.

In Photo 18 Neville is shown with

his younger brother, Ken Yeomans, in the bottom left picture. The top two

pictures show the use of tree belts to slow wind, slow evaporation and prevent

soil erosion. The placement of belts of trees was designed to fit in with and

complement all of the other design aspects. Trees belts were planted in varying

years along differing contour lines so that years into the future, prevailing

winds would come over a hill and skim over trees having their tops at the same

elevation even though the land was falling; that is, the tree belts became

progressively higher (and older) as the land fell. Time and the effect of

passing time were designed into the farm.

Photo 17 Neville at Keyline field day leaning

on the shovel

Photo 18 Keyline Photo set.

Thirty years after P.A.'s death, the system he established on the

farm still works by itself with little maintenance required. As can be seen from the

photo below taken in Oct 2001, when I

walked the farm with Stuart Hill the farm still looks like sweeping gardens or

a golf course.

Photo 19 Nevallan in 2002 looking back to the

Keypoint

P.A.

YEOMANS AND ONGOING ACTION

In 1971 P A. wrote his

book, ‘The City Forest: The Keyline Plan for the Human Environment Revolution.’

(Yeomans 1971). This book explores using Keyline in urban areas. On 24 April 1974 P.A. sent off to the

South Australian Government a design for a City Keyline Plan based on his book,

‘The City Forest’ for a proposed City of Monarto in South Australia. A copy of

these plans is in the NSW Mitchell Library (Yeomans and Murray Valley Development

League 1974). The proposal was for a population of 200,000 and

incorporated the use of city effluent for irrigation of forests to be planted

in the proposed city, and the purification of the surplus water by passing it

through the forest soil and biosystem. In keeping with connexity, the proposal

linked into the design reckoning, land-scale factors, as well as geological

structure and other features including: shape, form, climate, natural plant

cover, various soil types, capacities for development and use for the city,

climate factors - prevailing wind, pattern of temperature, annual rainfall,

amount and incidence of runoff, including all water that flows from outside and

across the cityscape, waste water, and water runoff from roads, roofs, and

sealed surfaces.

The Monarto plan mentions that, ‘Many

species of trees that grow in medium rainfall areas respond to the greatly

increased water and fertilizing factors of the effluents by producing several

times their normal timber and with improved cell and fiber structure. For

instance, trees for fence posts are available three years after planting. By

that time rainforest soil will have been created more than 150cm (5 feet)

deep. The plan was not followed through by the State Government of the day

(my italics).

Elias Duek-Cohen, who first

met Neville in 1968 through the Sydney Opera House Society (Neville was a

founding member), was at that time lecturing at Sydney University in Town

Planning. Duek Cohen told

me in January 2003 that through Duek Cohen’s efforts, university research is

currently under way sponsored by LandCom, the NSW Land Commission. That

research is testing the feasibility of a pilot project investigating P. A.’s

claims about producing deep soil using principles and

processes set out in P.A.s book ‘The City Forest’. The results should be

available later in 2003.

In his 1971 City Forest Book P. A.

acknowledges the seminal supporting role of Neville in the forming of his

ideas. He had Neville write the forward to this last book – The City Forest –

about adapting his ideas to the design and layout of a city (Yeomans 1971; Yeomans 1971).

Recall that Neville had evolved Fraser House back in 1959 when P. A. had

Keyline well under way. Neville worked closely with his father throughout his

years at Fraser House and Fraser House outreach in the years 1968 through 1971

when the City Forest Book was published.

In the 1970’s, Neville wrote a weekly column in the Now Newspaper

called ‘Yeomans Omens’ (Various Newspaper Journalists 1959-1974).

Photo 20 The Header to Neville’s Newspaper column in the Now

Newspaper

In this column he wrote that between

20-50,000 acres of Keyline forest could totally absorb and purify the liquid

effluent of Sydney. From this City Forest clean water would re-enter the rivers

and dams or the sea.

I sense competitive aspects in the relationship between P.A. and

his son Allan contributed to Neville being featured in the ‘Forward’ and

‘General Acknowledgements’ in the City Forest book. While fully recognizing

that Keyline was developed by the father, there is every indication that

Neville and Neville’s younger brother Allen were constantly involved and

contributing to unfolding action.

P. A .Yeomans wrote, ‘Keyline and

Habitat’ a paper he presented as a main platform speaker at the 1976 UN

conference, ‘On Human Settlements’ in Canada (Yeomans 1976) wherein he discusses Keyline and City

Forests. Eco-city projects are evolving around the world. Davis, a city of over

160,000 people in America, has adopted many of ‘The City Forest’s concepts,

including extensive edible landscaping and water harvesting in public places (James 1997). This landscaping is established and

sustained by volunteer community self help action. Resonant with P.A.’s, ‘The

City Forest’, a Global Conference on Eco-Cities was held in the village of Yoff

in Senegal in Africa in 1996. In describing Yoff, Nancy Willis (Willis 1996) quotes Robert Gilmen's definition of

an EcoVillage, ‘a human-scale, full featured settlement in which human

activities are harmlessly integrated into the natural world in a way that is

supportive of healthy human development, and can be successfully continued into

the indefinite.’ In describing her experiences during the Conference Willis

writes, ‘We would see a community which has traditionally lived in harmony with

nature instead of in competition with it. A community where cooperation for the

betterment of the whole has always been a given, and where governance has for

centuries been based on consensus decision-making and the idea that all should

participate. Neville’s work is resonant with the way of the people of Yoff.

In 1993, Ken Yeomans

published his book, ‘Water for Every Farm: Yeoman’s Keyline Plan’. This book

clarified some aspects of Keyline. Allan Yeomans informed me in

July 2002 that in keeping up the family’s tradition of being trail blazers, he

has completed the design phase and is poised for commercial production of large

scale solar thermal power supply system capable of servicing the needs of

100,000 people and way beyond. Allan has written the book, ‘Green Pawns and

Global Warming’ (Yeomans 2001) wherein he makes a claim that the World-wide application of

Keyline principles would get the carbon in the atmosphere back into storage in

the ground and this would give us a small amount of ‘breathing time’ to make

wider system changes.

Keyline’s

Influence on Permaculture

Neville said that Hill a professor of Social Ecology from the

University of Western Sydney understood the seminal part Keyline concepts and

practices played in the evolving of Permaculture by David Holmgren and Bill

Mollison (Mollison and Holmgren 1979.; Holmgren 2002). In a 2001 interview I had with David Holmgren, he stated that

Keyline was a key precursor in the development of Permaculture. Holmgren also

said that when he and Bill Mollison invited interested local people from around

Tasmania to see what they were doing with Permaculture, the people who turned

up were well versed in Keyline and were keenly following P.A’s innovations.

In a July 2000 interview, Hill told me that Lady Balfour, a world

famous agriculturalist from England had described Neville’s father as ‘making

the greatest single contribution to the development of sustainable farming in

the World in the past 200 hundred years’ (Mulligan and Hill 2001). Hill was particularly engaged with the way Neville had

adapted his father’s work in sustainable agriculture into the psychosocial

arena (Mulligan and Hill 2001; Hill 2002; Hill 2002). In a July 2002 conversation with Ken Yeomans, Neville’s youngest

brother, Ken said that Lady Balfour came to his father’s farms in Richmond and

P.A. visited Lady Balfour in England. These meetings between Balfour and P.A.

were confirmed by Stephanie Yeomans in July 2002.

Prophets for Ecological Profit

In all of this Keyline work, P.A. was

interested in earning money. Working with nature made economic sense. Suzuki

and Dressel give many examples of indigenous and other people engaging

ecologically with nature for sustainable living - often very profitably (Suzuki and Dressel 2002).

ADAPTING

KEYLINE TO CULTURAL KEYLINE

To place Keyline in this research, during the 1993 Yungaburra

conversation, Yeomans had mentioned that he had adapted his father’s Keyline in

evolving Fraser House, and in his extension of Fraser House ways into the wider

community. Neville called his adaptation, ‘Cultural Keyline’. The processes and

practices that P.A and his sons evolved on their farms, Neville adapted to both

the psychosocial and psychobiological fields.

To

briefly introduce Cultural Keyline, recall that P.A. and Neville had introduced

some changes to the soil environment. However, after they had done this, the

massive changes were self-organizing. The soil, organic matter, water

and detitrivores, as naturally occurring integrated systems, had emergent

qualities; that is, aspects started emerging, or coming into being, which had

not being present at lower levels of organization. In Cultural Keyline Neville

did similar enabling at the psychosocial level, and then left the social system

with its emergent properties to self-organize to richer levels of organization.

Neville did set up processes and structures to ensure social ecology was

maintained. Cultural Keyline will be discussed further in later Chapters. Both

Keyline and Cultural Keyline were informed by Indigenous ways.

So far in this Chapter we have

explored the Yeomans family’s evolving of Keyline and discussed aspects of

their farm designing and the Way they worked with nature to foster the

self-organizing emergence of abundant fertility. We have also introduced

Neville’s adaptation of Keyline to the psychosocial. Before I expand on that, I

explore some of the indigenous origins of the Yeomans’ Ways.

LINKS BETWEEN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE, PSYCHOSOCIAL CHANGE AND

INDIGENOUS SOCIOMEDICINE

It will be recalled that

Neville’s life was saved by a Indigenous tracker and twice nurtured by

Indigenous women following life threatening trauma. In times of personal struggle

with psychosocial survival, Neville was drawn to Indigenous healing way.

Indigenous influences on the Yeomans’ Way will now be considered.

Through P.A.’s work in

remote areas, the Yeomans family came in considerable contact with Aboriginal

communities. Neville would take every opportunity to experience their

nurturing, sociohealing and social cohesion practices. For Indigenous people

living as nomadic hunter-gatherers on this continent, social cohesion is a

central component of healing and vice versa. The concept of Indigenous

‘sociomedicine’ is implicit in psychiatrist Cawte's book, ‘Medicine is the Law’

and other writings (Cawte 1974; Cawte 2001). In remote areas of Australia, Aboriginal wellbeing may be

sustained by mutual support and staying with the group. When food and water are scarce everyone moved

on together. A pervasive aspect of indigenous healing is social cohesion (Cawte 1974; Cawte 2001). Typically, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

living traditional lives, bush remedies for a wide range of troubles are both

widely known and widely used. However, if in these contexts sickness is deemed

to have it’s source in social trouble - if social cohesion is under threat

- sociomedicine is used by only a few law people who know the ways. The focus

for healing or prevention is the whole

group and all become involved (Cawte 1974; Cawte 2001).

The

dance depicted in Photo 22 indelibly portrays the potency of a decision to part

company in the remote Australian Outback.

Photo 21

Parting of the Ways - Laura Festival in 2001.

Neville had firsthand experience of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories, sand drawings, rock paintings,

songs and dances and how all are used to maintain social cohesion in being well

together in community. The painting below is one of a set created by Tracy

Perrot, the niece of Aboriginal neurotherapists Norma and Geoff Guest who run

Petford Aboriginal Training Farm (now called Salem) as a therapeutic community (Salem International 2003). Neville knew both of these people

and acted as an enabling co-learning support person for them since the 1980’s.

Neville knew Tracy from when she was a baby. I interviewed Tracy in Jan 2001.

Photo 22

Tracy’s Painting Relating to Social Cohesion

In

the painting in Photo 22 Goanna Earth Life interacts with gold edged Eagle

Spirit Life and the child hand prints and all these mingle with other social

cohesion forms. Tracy Perrot’s summary of the social cohesion between

Aboriginal people and the pervasive cohesion between people and the wider Web

of Life as depicted in a series of her paintings, is as follows:

'Everything

in each painting is respective of what each thing in the painting gives up; the

stone, the birds, the people, as well as the words and the effect, the mystery,

the revelation - its all interconnected. The more we're a part of it, the more

we think about it, the more we have it in our mind - to look and appreciate -

we can feel it, and know that you are balancing - your balancing yourself out -

you're balancing your life to be in harmony with the Earth and everything that

lives in it, and everything you have been taught. The simple things in life are

the keys to success. And then being whole-some and balanced, I believe.'

Note the connexity in Tracy’s comments - connexion

continues between people, things, and between people and things such that they

are simultaneously interwoven, inter-dependent, inter-connected, inter-related,

and interlinked. I first met Tracy in 1991 when she

was a young girl. In 1992 while I was at Petford for six weeks enabling the ‘Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Drug and Substance Abuse Therapeutic Communities

Gathering’ (Petford Working Group 1992), Tracy outlasted the young Petford boys in riding the bull at the

Dimboola rodeo! I always knew her as Norma and Geoff’s niece who was around

from time to time. When I interviewed her for this research she bubbled forth

what may be called ‘spontaneous wisdom poetry like the above quote for about

thirty minutes. This interview was tape-recorded.

Neville evolved his social action on his understanding that for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, social cohesion among one's

people is paramount and is isomorphic with the cooperative inter-relationships

found in nature. Neville pointed out to me that in Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander run health centers, in keeping with their holistic way of thinking and

acting, instead of having mental health workers, these Health Centers have

psychosocial-cultural-emotional-spiritual health workers.

Both Neville and his father had been linked into these ways of

thinking and experiencing each other and the World. Neville had been accepted

into Yolgnu Aboriginal Communities living traditional lives in their homelands

in the Far North. Neville had experienced the storytelling and the singing and

the corroborees. He had gone hunting with them and participated in ancient

burial ceremonies that psycho-physically and metaphysically profoundly linked

Neville into extremely rich antiquities. Neville described these experiences as

equaling or surpassing any of the wisdom literatures he had read, and certainly

having or surpassing the richness of the mythologies of Grecian, Indian, Mayan

and other cultures.

Neville knew that the Mornington Island Aborigines tell, paint,

sing, dance, and the spirit didgeridoo players (Aboriginal wind instrument)

‘sing’ with their didgeridoo the story of the cooperation between the oyster

eater birds and the stingrays as a continual reminder to cooperate with each

other - they had observed how the stingrays bury themselves under the wet sand

as the tide goes out and wait for the shrill call of the oyster eater birds to

signal to the stingrays that they are again covered in sea water. Only a very

few Aboriginal didgeridoo players are spirit didgeridoo players.

As stated in Chapter One, Neville had firsthand experience of the

destructive social fragmentation occurring in Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Communities; the aggression, the abuse of women and children,

alcoholism, destructive eating habits, high mortality rates especially among

the young, criminal and psychiatric incarceration and the like. And yet for all

this, Neville saw in their life-ways processes that may have the potency to

have indigenous peoples transform themselves towards being Well, as well

as being a model for fostering transition

towards a humane caring Global Epoch.

Neville spoke of all manner of artistic expression and borrowing

from nature being used by Indigenous people of the Australasia Oceania Region

to sustain and enhance the social cohesion in their way of life. This artistic

expression and social action is called by some Indigenous people in the Region,

especially those in Vanuatu, ‘cultural action’, a term now being used

throughout the Oceania Australasia SE Asia Region (CIDA 2002; Queensland Community Arts Network 2002). Neville adapted this ‘cultural action’ into ‘cultural healing

action’ (Yeomans and Spencer 1993). Neville described Cultural Healing Action to me as combining and

embracing the

healing artistry of music making, percussion, singing, chanting, dancing,

reading poetry, storytelling, artistry, sculpting, puppetry, model making and

the like, and using any and all of these for increasing wellbeing. Neville was adept at using and enabling Cultural HealingAaction

and he enabled me to gain competences in using it as well.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wisdoms and practical action

embrace and embody a profound understanding of human socio-psychobiology and

its connexity with the best and worst in human conduct. For example

Langloh-Parker writes of the dreamtime story of Bunbundoolooey, which is a call

to mothers to ensure they foster compassion and caring in the male-child for

the protection of future generations (Langloh-Parker 1993). Continually retold for tens of thousands of years, this

shocking story of child neglect and abandonment and consequent matricide by a

compassionless son is a telling reminder of the need to instill compassion, and

the devastation and violence the absence of compassion can bring.

Neville understood the pervasive way Aboriginal sociomedicine is

linked into social cohesion. Before during and after Fraser House, Neville had an increasing

realization of the resonance between Keyline, Cultural Keyline and Indigenous

notions of Key Lines, Self/Earth-Mother unity, and unity between, and within

all human and non-human life forms. All of this experience was

melded into the Way Neville and his father used in evolving their farms. As

well, Neville’s experience with

Indigenous people had helped in the forming of his Way of Being and social

action in Fraser House and beyond. Neville constantly evolved

his Way towards evolving diverse social life worlds enacting values based upon

mutual caring loving respect between the sexes and the generations, peacefulness, economic equity, social

and political dignity and ecological balance (Yeomans 1974; Plumwood 1993; Plumwood

2002).

TIKOPIA

- CELEBRATING DIFFERENCE TO MAINTAIN UNITY AND WELLBEING

Neville searched the anthropological

literature for information about village life-ways that were inherently

constituting and maintaining social cohesion and well-being. He found that the

Tikopians were exemplars. Anthropologist Raymond Firth’s book on Tikopia Island

in the Solomon Islands East of PNG was one of many anthropological works

Neville read during his university studies (Firth 1957). It was the healing feel of the

communal village life on Tikopia depicted by the Firth and it’s resonance with

Neville’s notions of Cultural Keyline and his own early childhood experience of

Indigenous healing ways that so attracted Neville to use Tikopia as a model for

setting up Fraser House like a small Tikopia Village. None of staff and

residents I interviewed knew of this Tikopia connection (check Margaret

Cockett); however, Neville’s younger brother Ken’s first wife Stephanie Yeomans

confirmed it. Stephanie was a psychiatric nurse at Ryde Psychiatric Hospital.

Like the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Tikopians have

socio-healing and social wellbeing woven into the fabric of everyday life-ways.

When Firth was exploring Tikopia ways in the 1930's, the 1,200 Tikopians spoke

of themselves as 'tatou na Tikopia' - 'We the Tikopia', to declare their unity

and distinguish themselves from other islanders (Firth 1957).

Approximately three miles

long, the Island’s dominant feature is the remnants of a volcano surrounding a

fresh water lake. Two large rocky pyramids rise up from the shoreline left when

the balance of the volcano blew away.

The Island of

Tikopia

.

Tikopia Island has an intricate

system of reciprocal exchange spread as a network over the whole community of

communities. Firth stated that this reciprocity was continually ‘binding

(unifying) people of different (cleavered) villages and both sides of the

island (the two major regions) in close alliance’ (Firth 1957). The Tikopia celebrated difference to maintain unity. Firth

speaks of unifying processes among

the Tikopia that recognize, acknowledge, play with, respect and celebrate cleavages (difference/diversity) - that

is, ‘unifying cleavage’.

Firth writes of Tikopian

sociohealing wellbeing processes repeatedly involved ‘unifying-cleavage’. Some

examples - they would engage in ceremonial distributions of property, where the

principle was that as far as possible, goods go to the villages on the opposite side of the island - to those most

different. There would be periodic friendly inter-generational competitive

assemblies among those from differing villages, clans, and valleys. At these

periodic friendly competitive

gatherings and assemblies among those differing from them, the Tikopians would

engage in friendly competitive dancing, games and dart matches, as well as

share food and friendly fireside banter – what we have referred to as ‘cultural

action’. Tikopians had ceremonial distributions of property, where the

principle was that, as far as possible, goods go to the opposite district. An orchard of one clan group would be within the

territory of another clan group, bringing regular

contact in day-to-day life. There

were multiple unifying links between valleys, across ridges. According to Firth, ‘Still further are the cohesive factors of everyday operation,

the use of a common language, and the sharing of a common culture…(my

italics)’.

The men from the East could only marry

the women of the West. The opposite applied to the men of the West. That is,

people could only marry those most

different. The new brides would live with their husband’s family. As land was

passed from mother to daughter, the couple would set up gardens on land

belonging to the wife’s mother (Matrilineal), - that is, on the opposite side

to where the couple were living. Each morning all the gardening couples from

the East would get up at sunrise, bath and have breakfast. They would then make

the climb through gaps in the volcanic ridge. The sun rose a little later for

those on the West and when the couples from the West reached the top, the other

partners would act as hosts as they had a small party for a while. They would

also exchange news and banter before going to their respective gardens. The

process was reversed in the evening. The sun would set first for those

gardening in the East. So they would climb first and wait to be hosts for

another party. There would be more chatting, drumming and dancing in the late

afternoon light, and as the tropical sun set in the West, they would all return

to their respective villages. There they would have exchanges of vegetables for

fish with the villagers who were the seafarers - another different group to

celebrate with. Often these beach exchanges were occasions for more dancing and

friendly play. After dinner, the party would resume on the beach, or perhaps

some would walk across the smaller ridges to visit villagers in the neighboring

valleys. Firth uses these notions of unity and cleavage in the following quote

from page 88 of his book, ‘We the Tikopia’ (Firth 1957):

‘A still further

complicating factor is the recognition of two social strata, chiefs and

commoners, which provides a measure of horizontal

unity in the face of vertical

cleavage between clans and between districts. In former times there was

even a feeling that marriage should take place only within the appropriate

clan. Important, again are the intricate systems of reciprocal exchange spread

like a network over the whole community, binding

people of different villages and both sides of the island (the two major regions) in close alliance’ (my italics).

Neville and other

researchers at Fraser House used the above notions of horizontal unity in the face of

vertical cleavage in doing sociogram research into the friendship patterns

among staff and patients in Fraser house. This is discussed in Chapter Four

In all this celebrated

difference, villagers were always in constant contact as they passed each other

on the mountain trails and met on the beaches. There were multiple unifying

links between valleys and across ridges. The Tikopia people celebrated

their diversity to create social unity and cohesion.

A

PSYCHIATRIC UNIT MODELED ON A SOUTH PACIFIC ISLAND

In forming Fraser House in

his mind before he started it, Neville was searching for models of a small

communal village with a way of life that is inherently

wellbeing sustaining and healing. In this, Neville was seeking to create

Tönnies' ‘Gessellschaft’ – a small friendly village where everybody knows

everybody (Tönnies and Loomis 1963). Neville was inspired by the healing and integrative aspects of

small village life as explored by Tönnies in his book, ‘Gemmeinschaft and

Gessellschaft’ (Tönnies and Loomis 1963). This fitted with Neville’s experiencing of the healing potency

of Aboriginal women’s sociomedicine and his extensive readings in anthropology seeking

healing aspects of Indigenous ways.

Firth made no comment throughout his book that the

Tickopian communal village life and mores may be helping to constitute and

sustain individual and communal psychosocial wellbeing. More importantly in the

context of this thesis, Firth makes no comment about the potential of the

Tikopian’s way of life as a practical working model for restoring psychosocial health and wellbeing in dysfunctional

people, families and communities. This possibility was recognized by

Neville and used by him, in association with his Cultural Keyline concept, in

forming and structuring Fraser House as a psychiatric unit based on therapeutic

community principles. Neville recognized that implicit in Firth’s writing was

that the Tikopian’s inter-village and intra-village living and mores helped

constitute and sustain individual and communal psychosocial well-being. Notice

that their psychosocial well-being processes were woven completely into every aspect of their lives together.

Neville drew on the Tikopia way in the design of the Fraser House buildings and

his structuring of the flow of people in the Unit. He evolved a contained space

for the mad and bad to live closely together as a ‘village community’.

Neville saw the Tikopia

way of life as resonant with Australian Indigenous sociomedicine where

psychobiological healing energy could be easily and spontaneously passed along

to others as the need arises as people go about together in their every day

social-life world. On Tikopia there was constant linking within and between

people of differing generations, gender, clan, village, locality, status

(chief/non-chief families) and occupation, that is, between differing

sociological categories. Neville’s use of cleavering Fraser House

Family-Friendship Networks and inter-patient factions by sociological

category is discussed in Chapter Five. When Firth was writing there were

about 1,200 Tikopians. Firth discussed cohesiveness within the exploration of

clan membership as one framework for having an anthropological understanding of

the Tikopians.

As with Tikopia, in Fraser

House, the lives of all involved were linked to place and places. This created

public space. Public space was community space, where people were in continual

close social exchange - where friendships blossomed and were sustained by

regular contact (Cf. Tönnies' Gessellschaft (Tönnies and Loomis 1963)). For Tikopians, the top of the mountain, along all the trails,

within the villages, on the beaches - these were all public spaces -

places for sharing, caring, and nurturing. Social news was continually

circulating. Neville created isomorphic trails in the long winding corridors in

Fraser House. Tikopia life was not without some contention and strife; with all

of the constant social exchange, any strife soon became common knowledge and

typically, it was interrupted before it could start. There was always a support

network to call on to resolve any issue. How Neville set up similar processes

and used similar social forces in Fraser House is discussed in Chapters Four to

Seven.

In Tikopia, the common

stock of practical wisdom was so readily passed on that it was widely held

within the communities. People knew ‘what worked’. Socio-healing was not an

‘add on’. It was not a ‘government or private sector service’. It was community

embedded mutual-help and self-help. All of this socially embedded well-being

action was pervasively holistic. These socio-healing actions were preventative.

They sustained wellbeing. They were the norm. They constituted their good life.

They perpetuated in Maturana’s terms ‘Homo Amans’ (loving people) (Maturana, Verden-Zoller

et al. 1996; Maturana, Verden-Zöller et al. 1996). Their social life world was ‘self authenticating’ and

self-healing (Pelz 1974; Pelz 1975). In Neville’s view, Tikopians lived therapeutic community in

celebratory links with other therapeutic communities on their island. Neville

said that with dysfunction at a minimum, the term ‘therapeutic community’ more

appropriately becomes, ‘well-being community’. Tikopians sustained cultural

locality – within villages, on both sides of the island and at the whole Island

level. Zuzenka Kutena introduced me to the term ‘Cultural Locality’ (Kutena 2002). ‘Locality’

is used as meaning ‘connexion to place’. ‘Cultural locality’ then means, ‘A way

of life together connected to place’. Zuzenka started the ‘Vox Popali’ program

on SBS, Victoria’s intercultural media. Zuzenka’s actions are discussed further

in Chapter Nine.

Neville’s aim was to

create self organizing communal

living which may impact upon and create shifts away from isolation and

destructive cleavage, or make functional cleavage in entangled pathological

networks towards people mutually helping each other in developing a functional

integrated individual and family-friendship unity in living within functional

social and community networks.

Note that with both

Australian Aboriginals and the Tikopians, the concept of ‘cleavages’ and

‘unities’, and ‘cleavered unities’ recognizes,

respects and celebrates the

cleavered. Another similar notion to ‘cleaver’ used by the Aboriginal Yolgnu

people of the Australian Far Top End, may be loosely translated ‘rupture’. This

is not used in the sense of ‘torn’ or ‘damaged’, rather, that there is a very

distinct and important differences between two or more entities or things that

are being recognized and maintained. Neville knew from personal

experience of the Australian Aboriginal Yolgnu people that Tikopia’s

celebration of cleavered unities has similarities to the Yolgnu experience and

concepts in their social interaction and trade with East Timorese Sea Gypsies

and Malaccans. Neville told me that for the Yolgnu, difference was celebrated,

especially when East Timorese Sea Gypsies and Malaccans traders arrived. There

was no thought among the Yolgnu of wanting to change their visitors, though

sharing time with their visitors created a palpably different reality for their

time together. For the Yolgnu, this temporary different shared reality is

recognized as remarkable, wondrous and marvelous.

ASSAGIOLI

AND PSYCHO-SYNTHESIS

In Dec 1993, Neville

suggested that Assagioli’s (Assagioli 1971) writings on Psycho-synthesis were resonant with Neville’s Way,

and Firth’s concept of ‘cleavered unities’. In giving a big picture of

Psycho-synthesis, Assagioli speaks of cleavered unities being evolved towards

the ideal through love. Recall that Maturana has resonant ideas in his paper,

‘Biology of Love’ (Maturana, Verden-Zoller

et al. 1996; Maturana, Verden-Zöller et al. 1996). The following is a resonant excerpt:

‘From a still wider and more comprehensive point of view,

universal life appears to us as a struggle between multiplicity and unity, (ed: in other words cleavage and unity) a labor and an inspiration towards union. We

seem to sense that - whether we conceive it as a divine Being or as cosmic

energy - the Spirit working upon and within all creation is shaping it into

order, harmony, and beauty (ed: refer Neville’s values research in Chapter

Five), uniting all beings (some willing but the majority as yet blind and

rebellious) with each other through links of love, achieving slowly and silently, but powerfully and

irresistibly - the Supreme Synthesis (Assagioli

1971, p. 31) (my italics).’

During

our 1993 Yungaburra conversations Neville specifically drew parallels between

Assagioli’s following nine aspects for interpersonal and social Psychosynthesis

and Fraser House process (Assagioli

1971, p. 64):

1. Comradeship

- Friendship

2.

Cooperation - Team work - Sharing

3.

Empathy

4.

Goodwill

5.

Love (Altruistic)

6.

Responsibility (Sense of)

7.

Right Relations:

a) Between the Individual

and the Group

b) Between Groups

8.

Service

9.

Understanding - Elimination of Prejudice

All of these nine aspects

were central to Fraser House change processes as will be discussed in Chapters

Four to Seven.

While Psychosynthesis typically

focuses on the individual, Assagioli speaks of healing the

individual/group/community as suggested in the following use of notions of

cleavered unity (my italicized duplexes).

‘Thus inverting the

analogy of man being a combination of many

elements which are more or less coordinated,

each man may be considered as an element

or cell of a human group: this group, in its turn, forms associations with vaster and more complex groups, from the family group to town and district groups and to social classes; from workers’ unions and employers’ associations to the great

national groups, and from these

to the entire human family.’

‘Between these individuals

and groups arise problems and conflicts which are curiously similar to those we

have found existing within each individual.’

‘Their solution

(interindividual Psychosynthesis) should therefore be pursued along the same

lines and by similar methods as for the achievement of individual

Psychosynthesis.’

This

last point is resonant with Neville’s Way of working simultaneously with

psychosocial (inter-individual) and psychobiological (intra-individual)

systems. Neville also drew my attention to the connection between Assagioli and

Taoism. Assagioli states that Psychosynthesis is or may become:

‘a method of treatment for

psychological and psychosomatic disturbance when the cause of trouble is a

violent and complicated conflict between groups of conscious and unconscious

forces.’

One aspect of this uses the

Taoist notion of, ‘letting Life act through them’ (the Wu-Wei)(Assagioli

1965, p. 27). Recall

from Chapter One that Neville was familiar with and drew upon Taoist thought

and Way.

RE-COGNISING CONNEXITY

Earlier I defined the word ‘Connexity’ as a relation between contexts/things that are

simultaneously inter-dependent, inter-connected, inter-related, interlinked and

interwoven. All contexts/things have this connexity relation between everything

involved. The person(s) sensing and using connexity has it as a multi-aspect

bond between themselves and the context/things that flavors all of their

connecting as ‘inter-dependant connecting in relating’. Sensing and using

connexity raises the possibility of understanding the other’s nature and way of

being and acting, and including this understanding in the connecting.

Narby has written, ‘microbiology’s

description of the pervasive sameness of DNA in all living things proclaims the

fundamental unity in nature (Narby 1998, p.110). Connexity

is an intrinsic property of all life and non-life on Earth. Globally,

Indigenous people hold this universal inter-relatedness as fundamental. The

photo below is of an Australian Aboriginal corroboree where the nature and way

of the crocodile is embodied by all involved, especially the young people. They

share the same locality as the crocodiles and typically come to no harm as they

live in connexity relating with the crocodiles.

Photo 23 Embodying Crocodile Ways

This universal inter-relatedness is not something we set up –

though we can enrich contexts by juxtapositioning. Connexity is

already pervasive in and between both

the human social life and the natural life world whether we sense it or

not! Neville was profoundly influenced by this understanding and embodied

it as his way of being and acting.

It is little known that

Neville modeled the Fraser House upon the Indigenous socio-processes and upon

Keyline Ways. More aspects of Neville’s Way and practical examples of this way

will be occurring throughout the rest of this Research. More detailed

specifying of Neville’s micro-behaviors is given in Chapters Four through

Seven. Given the innovative and societal change-work both Neville and his

father achieved in their life, very few people know of them. Dominant elements

had a vested interest in ensuring this was the case. This theme is discussed

throughout the Research.

REFLECTIONS

This Chapter has traced

the evolving of Neville Yeomans’ Way of being and action that he used in his

life- work. It traced the evolving of Neville’s Way firstly, from the joint

work he did with his father and brother Allan in evolving sustainable

agriculture practice, and secondly, from prior links that both Neville and his

father had to Australian and Oceania Indigenous way. The Chapter then traced

Neville’s adaptation of these influences into the psychosocial and

psychobiological spheres in evolving the structures and processes of Fraser

House. This adapting is extended in the next Chapter.

(2002). The Development Of

Narrow Tyned Plows For Keyline - Internet Source - http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010125yeomans/010125addendum.html.

Assagioli, R. (1965). Psychosynthesis;

a manual of principles and techniques. New York,, Hobbs Dorman.

Assagioli, R. (1971). Psychosynthesis

: a manual of principles and techniques. New York, Viking.

Capra, F. (1997). The

Web of Life - A New Synthesis of Mind and Matter. London, Harper Collins.

Cawte, J. (1974). Medicine

is the law : studies in psychiatric anthropology of Australian tribal societies.

Honolulu, University Press of Hawaii.

Cawte, J. (2001). Healers

of Arnhem Land. Marleston, SA, J.B. Books.

CIDA (2002). CIDA