CONTENTS

CHAPTER SEVEN – CRITIQUING AND REPLICATING

CRITIQUE OF

FRASER HOUSE IN THE SIXTIES

REPLICATING

FRASER HOUSE IN STATE RUN ENCLAVES - KENMORE HOSPITAL’S THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY

FRASER HOUSE

AND TRANSITIONS TO COMMUNITY SELF CARING

NEVILLE ACTIONS

TO PHASE OUT FRASER HOUSE

FRASER HOUSE A

MODEL FOR AMERICAN RESEARCH

ETHICAL ISSUES

IN REPLICATING FRASER HOUSE

FIGURE

Figure 1 The Four Levels for Maintaining Conduct

and the Correcting Processes

Figure 2 The Four Levels and Total Institutions

PHOTOS

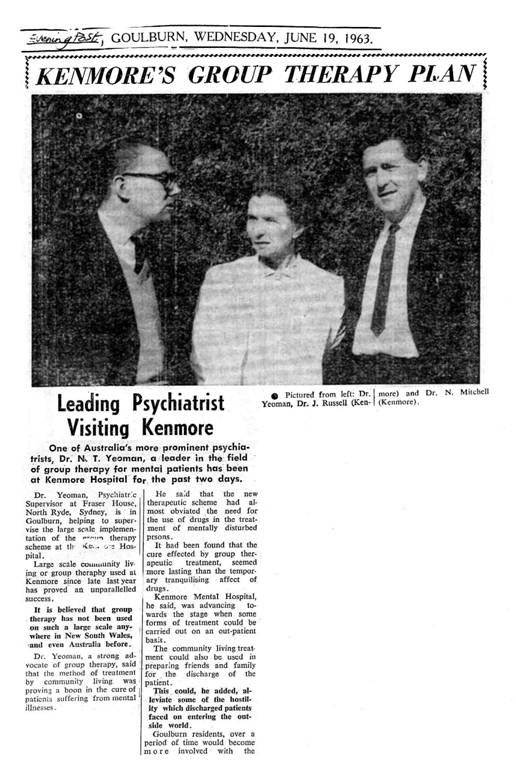

Photo 1 Dr. Yeomans at Kenmore - Goulburn Evening

Post, 19 June 1963.

ORIENTATING

This Chapter discusses

criticisms made in the Sixties about Neville and Fraser House and responses to

these criticisms are made. Neville’s processes for extending Fraser House into

the local community are detailed. Wider society’s processes for placing

boundaries upon behavior and for accommodating diversity is detailed and these

are contrasted with Fraser Houses and the Laceweb’s use of therapeutic

community to fulfill the same functions. Neville’s setting up of transitions to

community self-caring is set out, as well as Neville’s intentional actions contributing

to the phasing out of

Fraser House. Research on Fraser house evaluation is

briefly outlined along with a discussion of American research using Fraser

house as a model. The Chapter concludes with ethical issues in replicating

Fraser House.

CRITIQUE OF FRASER HOUSE IN THE

SIXTIES

In summing up Fraser

House, the response of those involved in Fraser House ranged from rapturous

commendation to rapping condemnation. In their book about Fraser House Clark

and Yeomans report (Clark and Yeomans 1969):

‘Many

professional workers, psychiatrists, psychiatric workers, psychiatric nurses

and clinical psychologists, have expressed antagonism towards the practices of

the Unit. They have claimed, among other things, that the confidences and the

dignity of patients are not respected in the traditional way, and that the

treatment is crude and administered by unskilled personnel. They describe

instances in which relatives of a patient have been denied information about

the progress of treatment, or had pressure exerted upon them to attend group

therapy meetings against their own wishes.’

‘At a more personal level,

charges of flamboyance and irresponsibility have been made against the director

of the unit (that is Dr. Neville Yeomans). Some practitioners have refused to

refer patients to Fraser House because of their feelings of disquiet about it’s

personnel and practices.’

‘Some patients, also and

their relatives and friends, have shown extreme fear of, and hostility towards

the practices of the Unit. They describe vividly their feelings of horror and

helplessness when first exposed to the interrogation or verbal attack of a

group of grossly disturbed people. Frantically, they look towards the staff for

protection, but support is not forthcoming. The inescapable conclusion is

reached: staff and patients are united in their efforts to uncover innermost

secrets and to probe sensitive emotional areas without remorse.’

Some of these charges were also

made against Neville’s father. He was described as being unprofessional,

unskilled in agricultural science and with being too forthright. Similar

charges of being unprofessional and unskilled are made against Laceweb people.

A RESPONSE

I will

respond to these criticisms; firstly, the report that ‘relatives/friends of a

patient had pressure exerted upon them to attend group therapy meetings against

their own wishes’. We have discussed that ‘family and friends attending Big

Group’ was a condition for patient entry to the Unit. We have also seen a

letter sent to friends and relatives encouraging them to attend. That letter

said that if requested, a group of patients could call on friends and relatives

to explain things, and answer questions. In respect of the claim, ‘that

pressure was being exerted against people’s wishes’, Neville stated that this

certainly occurred fairly regularly as particular circumstances arouse.

Some families went out of their way to

not cooperate with efforts to treat family members. Neville wrote, ‘Family

inconsistency and conflict, distrust of the hospital, etc is most commonly and

in fact almost solely found amongst the relatives of the most severely ill of

all patients. It characteristically arises with the relatives of severely

schizophrenic and major narcotic addicts, murderers, and violent patients; far

more than in any other group which is perhaps a reflection of the extreme

tension and distortion under which these families live, making them suspicious

of any efforts to help them (Yeomans 1965, Vol 5, p. 44-45)’.

The

following is an example Neville recalled - a tangled inter-generational

inter-family dysfunctional group of six. Firstly, two of the group were

attending Fraser House - a brother and sister in their early twenties. After a

time they brought along a fourteen-year-old friend of the sister who revealed

she had been living in a criminally exploitative sexual relationship with a man

in his fifties for many months. He had also being taking illegal photographs of

this fourteen year old. She had moved in with this fellow, a mate of her

father, after the father had been sexually abusing her. The fourteen year old

had confided all this to the brother and sister.

The

brother was incensed about this fellow exploiting the 14 year old as he knew

his sister, the one attending Fraser House with him, had been sexually abused

by their father. The brother and the fourteen year old stole the man’s

expensive photographic equipment as payback for exploiting the girl. Because of

this they had been charge by the police. All this was revealed to everyone in

Big Group. The Big Group decided that six of the competent mature-aged patients

(none of those involved in the focal group, and some who had themselves been

exploiting children) would confront this fifty year old. The fourteen year old

moved all her gear out of the man’s house in his absence and she shifted in to

Fraser House. Around 8:30PM on a dark night this fellow answers a knock on the

door to find five psychiatric patients on his doorstep. Neville told me that

the spokesperson said words to the effect, ‘We are all friends of the young

girl you have had her living with you, and we know everything, and it is in

your interest to let us in come in and talk with you’. He let them in. The

spokesperson continues, ‘We are all patients at Fraser House. Do you know

Fraser House?’ He did.

‘One

hundred and eighty people in a Big Group talked about you and the 14 year old

girl at length today. You can go to jail for a long time for what you have been

doing. It is very much in your interest to attend Fraser House reception at

9:20 A.M tomorrow morning for a meeting starting sharp at 9:30 A.M.’ He was

there.

Apart

from anything else, this fellow had been placing his own wellbeing in extreme

danger without a single thought of consequences for him. He needed help, though

at first he did not know it. The man attended Fraser House Big Group and Small

Groups processes regularly thereafter. Initially, the brother and sister, the

14 year old, and the fifty year old were allocated to different Small Groups.

After a time, two or more would attend the same Small Groups. Ultimately the

brother and the fourteen year old faced court where their reason for taking the

photographic equipment, the older man’s exploiting the fourteen year old, and

the fact that the two of them and the fifty year old had been attending regular

therapy groups at Fraser House, were all taken into account as mitigating

circumstances. Because of their evidence in their trial, the fifty year old was

taken into custody by police and let out on bail. He continued attending Fraser

House as an outpatient and this was put forward as something in his favor and

taken into account in his sentencing. Readers can draw their own conclusions

about the efficacy of the pressure to attend Fraser House in this case.

As for

the claims that the treatment was crude and administered by unskilled

personnel, the reports of those I interviewed was that patients and staff alike

became extremely competent in a whole range of processes outside of

conventional mental health practice. The Unit became the center for teaching

new psychiatrists ‘community psychiatry’. Fraser House patients played the

major role in training these new psychiatrists. In respect of the criticism that

confidences and the dignity of patients were not respected in the traditional

way, we have discussed the often tough and provocative nature of Fraser House

community process. Neville described his Way as being ruthlessly compassionate

in intervening, interrupting and sabotaging people who were adept at

maintaining and sustaining their own and/or others’ dysfunction.

In Fraser

House people changed where nothing else had worked in the other places they had

been. Relatives and friends of a patient

were often denied information about the progress of treatment. It was

regularly found that many relatives and friends were very prepared to use

information about a patient’s progress to destructively sabotage that process.

It is to be expected that

what Neville was doing would create ‘peer disquiet’ about Fraser House

personnel and practices. Anything that turns a profession on its head and

strips away virtual every aspect of members of that profession’s traditional

power and authority as both individuals and as a profession would create

vehement opposition.

Each of my interviewees

agreed that the following quote encapsulates the experience of many

newcomers to Big Group.

‘Some patients and their

relatives and friends have shown extreme fear of, and hostility towards, the

practices of the Unit. They describe vividly their feelings of horror and

helplessness when first exposed to the interrogation or verbal attack of a

group of grossly disturbed people. Frantically, they look towards the staff for

protection, but support is not forthcoming. The inescapable conclusion is

reached: staff and patients are united in their efforts to uncover innermost

secrets and to probe sensitive emotional areas without remorse (Clark and Yeomans 1969).’

Every interviewee,

including the ‘ex North Shore Bus Depot Gang’ leader and the outpatient I met

in Yungaburra said that Big Group was an extremely intense experience and in

all of this, there was profound framing compassion and a relentless drive for all

involved to be moving to being able to live well in the wider community. As for

being flamboyant, Neville was a chameleon who constantly changed to fit

context. In keeping Fraser House before the public of Sydney, Neville was very

prepared to be a flamboyant celebrity. Later, when he was quietly evolving

networks among Indigenous people and wanting to minimize interference from

dominant elements, he went out of his way to be invisible. In chasing up some

people in Sydney in 1998 and 1999 who knew Neville in the Sixties, a number

said they thought he had died years before.

REPLICATING FRASER HOUSE IN STATE RUN

ENCLAVES - KENMORE HOSPITAL’S THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY

Dr. N. M. Mitchell from Kenmore Psychiatric

Hospital in Goulburn was interested in setting up a 300 patient therapeutic

community (based on Fraser House) within Kenmore, a hospital with over 1,200

patents (Mitchell 1964). A file note in Neville’s collected

papers states, ‘Dr. Mitchell was sent to Fraser House for a week of intensive

training and received copies of Fraser House’s rules, administration structure

and committee organization. Neville had visits to Kenmore and visited Goulburn

Base Hospital and developed liaison between Goulburn Base Hospital and Kenmore.

Neville engaged in four days of continual supervision at Kenmore during one

phase when he ran small and large groups in every ward of the hospital

and delivered talks to all members of both staff and patients

throughout the entire hospital’ (over 1800 people). He also supplied

Kenmore with research instrument to act as case history records. While their

therapeutic community had around 300 patients Neville ensured all involved

in Kenmore and the local hospital knew about this new Unit (my italics) (Yeomans 1965, Vol.

12, p. 66-69). Note the

thoroughness of Neville in ensuring every single patient and staff as well as

the local base hospital all were thoroughly briefed on the new therapeutic

community unit at Kenmore.

Photo

1 Dr. Yeomans at Kenmore - Goulburn Evening Post, 19 June

1963.

Neville’s work with Dr. N.

Mitchell and Dr. J. Russell at Kenmore was featured in an article in the

Goulburn Evening Post on 19 June 1963 called, ‘Kenmore’s Group Therapy Plan –

Leading Psychiatrist Visits Kenmore’ (1963). Dr. Mitchell is quoted as saying, ‘A large-scale community

living or group therapy used at Kenmore since late last year has proved an

unparalleled success. Kenmore modeled their Committee structure/process on the

one then in use within Fraser House.’

FRASER HOUSE AND TRANSITIONS TO

COMMUNITY SELF CARING

This segment looks at

Neville’s contextual frames for positioning Fraser House praxis in fostering a

transition to a humane caring epoch. Neville spoke of Western society having

four levels of functioning relating to conduct - namely, values, norm, rules,

and obligations. Figure 1 shows firstly these four levels, secondly, the normal

and deviant behaviors associated with each of the four, and thirdly, the

typical societal ‘correcting’ agencies associated with each level.

Typically, criminal people

are deviant at levels one, and three in addition to level two. The criminally

insane are typically deviant on all four levels. The mentally ill may deviate

at level one and three as well as level four.

Note that these mainstream

agencies provide a ‘service’ role for the community at large. In other words,

they ‘do it for us’. In large part, level two and three service is provided by

some level of government - the public sector.

Some private sector

contracting-out occurs; for example, private prisons. Private commercial

practitioners (service providers) may be supported by government funding

arrangements; for example psychiatrists and physicians in level four. Voluntary

service providers also assist; for example, church based social and counseling

services and youth-outreach services in level one and aspects of level four.

Outside the massive service provider arrangements is now an extensive network

of self-help groups.

LEVEL |

NORMALITY |

DEVIANCY |

CORRECTING PROCESS |

FRASER HOUSE AND

LACEWEB CORRECTING PROCESS |

|

|

1 Values |

Moral Ethical |

Immoral Unethical |

Priests Moral leaders |

Therapeutic Community |

|

2 Norms (Legality) |

Legal Law-Observance |

Illegal Criminal |

Judiciary Police |

Therapeutic Community |

|

3 Rules (Efficacy) |

Loyal |

Disloyal |

Administrators |

Therapeutic Community |

|

4 Obligations (Capacity) a) Role Performance b) Task Performance |

Role responsibility (Competence) Ability |

Mental Illness Physical Illness (Disability) |

Psychiatrist Physician |

Therapeutic

Community Therapeutic

Community |

Figure

1 The Four Levels for Maintaining

Conduct and the Correcting Processes

They blossomed in the

Seventies and Eighties, in large part because of the enabling impetus of

Neville in the Sixties and early Seventies. This is discussed later in this

Chapter. An example is the extensive directory of the Coalition of Self Help

Groups in Victoria (COSHG) (Coalition of Self Help

Groups 2002). A board member of COSHG

accompanied me from Melbourne to Yungaburra in Far North Queensland in 1993 to

stay with Neville and experience Laceweb action. This is discussed later in

this Chapter and in Chapter Eight.

The social-pathology

support framework of Fraser House and the Laceweb assumes that resident

behavior is a function of pathological social networks - a failure at the

community level, and also assumes it is in part a function of pathology within

the wider society. While Fraser House was a service provided by the NSW Health

Department, life within Fraser House was pervasively self help.

Within Fraser House there

was no service based correcting agent - where ‘agent’ means someone who does something for you’ – rather, within Fraser House the correcting, remedial and generative processes operating at all

of the four levels of functioning depicted above in Figure 06 becomes the

therapeutic community, which by it’s nature, is bracketed off, though embedded

in local community. In Neville’s framework, the notion of ‘service delivery’ by

‘expert’ ‘corrective agencies’ is replaced by self-help, and mutual

or community help by the therapeutic community. This is resonant

with Indigenous community sociomedicine for social cohesion. The therapeutic

community is supported by nurturing enablers as ‘resource people’.

In Fraser House, Residents

explored, clarified and developed their values and reciprocal obligations together.

They developed their own community lore, law, rules, and norms. They

were living within wider and more functional rule and norm systems that they

were evolving and continually reviewing together as a caring

community. This co-reconstituting of the rules and norms they lived by was

embedded within every aspect of communal life in Fraser House. The lore, law,

rules and norms embodied humane caring self-help and mutual-help. These rules

and norms were never reified – as if they were immutable and coming from God.

As Kuhn pointed out in his writings about the potency of paradigms (Kuhn 1962; Kuhn 1996), the processes constituting and sustaining societal paradigms are

reified and rarely if ever noticed or questioned. Neville created a context

where the social constituting of their shared reality was made explicit

and kept under continual review by the Fraser House community. Goffman had

written about various types of total institutions. Neville fitted them into the

above framework of values, norms, rules, and obligations as depicted in Figure

07.

LEVEL |

CAPABILITY AND NATURE |

INSTITUTION |

CONFORMING

PROCESS |

|

|

1 Values |

Capable and in retreat |

Abbeys, Monasteries,

Convents |

Priests Moral

leaders |

|

2 Norms (Legality) |

Capable and deliberate

threat to society |

Jails, Penitentiaries, POW

Camps, |

Judiciary Police Guards |

|

3 Rules (Efficiency) |

Capable and there for

instrumental purpose |

Army Barracks, Ships |

Administrators |

|

4 Obligations (Capacity) a) Role Performance b) Task Performance |

Incapable and unintended

threat to society Incapable and harmless |

TB Sanatorium, Mental Hospital Blind, Orphaned, Aged,

Indigent |

Physician,

Psychiatrist Physician,

Carer |

Figure 2 The Four Levels and Total Institutions

My ‘Comparison of Goffman’s, ‘Total

Institutions’ and Fraser House’ is in Appendix 10.

Recall that Neville

described Fraser House as a, ‘transitional community’ as it was continually

adapting to meet changing contexts and challenges. There was a culture of

continual improvement in being well – wellbeing. Neville described all this as

a ‘micro-process’ that may be used in returning a way of being and living

together to wider society in Australia – a culture that has been subject to the

cultural stripping by the Rum Corp at the very start of European settlement in

Australian - where in Neville’s terms,’ Irish and other settlers and local

Aborigines alike all had their culture stripped systematically from them and a

military culture imposed’. Neville embedded the framework depicted in the above

table into the evolving Laceweb. The distinction between mainstream ‘service

delivery’ approaches and the self-help Laceweb model is discussed in Chapter

Nine.

Figure 3 is an extension

of Figure 1 and depicts the way society accommodates diversity between people,

socio-economic groups, ethnic groups and cultures. Societies have varying

degrees to which they will allow protest and dissent. There are correcting

processes for resolving deviancy from within or from outside the society. The

right-hand column gives the Fraser House/Laceweb healing processes for healing

deviancy in all it’s forms towards having cleavered unities that respect and

celebrate diversity. All of the above was continually discussed within the

Fraser House community. Patients would typically leave Fraser House with a

large family friendship network, competencies in administering a substantial

organization, and have a functional practical knowledge of sociology and

competency in community therapy. It was little wonder that shortly after

leaving Fraser House in 1968, Margaret Cockett was finding ex-patients popping

up around Sydney engaged in local self-help action. Typically, she found that

ex-patients were very effective in

group process and action as they had had excellent experience and grounding

during their Fraser House stay. When the going got turgid and emotions heated

up in these action meetings it was nothing that these ex-Fraser House residents

and outpatients had not already experienced in Fraser House.

|

Level |

Normality |

|

Correcting Process |

Fraser House/ Laceweb Correcting Process |

|

Cleavage iversity |

Current

way: Oppressor/ Oppressed Advantaged/ Disadvantaged Subjugator/ Subjugating Exploiter/ Exploiting Possible

way: Harmonious Unity |

Protest Disobedience Conflict Sabotage Insurrection War Terrorism |

Venting energy Fines Compelling

compliance Coercion & sanctions Imprisonment Warrior system -

yang Political Mediators Negotiation Police/Military Para-military Militias Torture & Trauma Shaming & Maiming (Towards

status quo in current way) |

Cultural Keyline Healing nurturing – Yin Therapeutic Community Mediation Therapy Peacehealing Healing/Wellbeing networks Festive,

and celebratory gatherings Everyday

life wellbeing processes (Towards

possible way of harmonious cleavered unity) |

Figure 3 A Table Depicting the Way Society and Fraser House/Laceweb Accommodate

Diversity Between People, Socio-Economic Groups, Ethnic Groups and Cultures.

Margaret recalled one

Fraser House ex-patient as been a very angry person at Fraser House. When this

person was leaving Fraser House, Margaret thought that he had a ‘long way to

go’ in being ‘functional’. She met and talked to him at a social action

meeting. Margaret told him that she was surprised to find him there and said

she thought he would be ‘railing against the government’ rather than being

involved in this self-help action. Margaret said he replied words to the

effect, ‘You have it all wrong. Change is happening at the everyday life level. It is useless trying to change the Government

and the large power processes.’ This response was in fact resonating fully with

Margaret and Neville’s view. It also resonates with Rowan Ireland’s “Sitting on

Trains” article regarding social movements in Brazil (Ireland 1998). Irelands paper is discussed in Chapter Nine.

Professor Ross Thorpe, the

Head of Social Work at James Cook University when I started this research

project in 1998, told me in November 1999 that when in the mid Seventies she

was a new arrival in Sydney from the UK, social workers were continually

talking about what happened in Fraser House in the early 1960’s.

During mid 2002 Alex Dawia

- one of my Bougainvillian friends- and

I had been invited down to Hobart to link and share with Tasmanian wellbeing

networks. A series of gatherings were held involving healing ways sharings

including Bougainville traditional Ways and Cultural Healing Action. These

networking ways are discussed further in Chapters Nine and Ten. A casual

conversation with a woman giving me a lift to the airport in Hobart, Tasmania

after these gatherings revealed that she and many of the friends in Tasmania,

especially Hobart in the late Sixties and early Seventies closely followed

Neville and Fraser House developments and used these as inspiration to push for

all manner of changes in that state’s Community and Family Affairs departments.

She said that they had many successes and that they evolved very effective

wellbeing networks throughout Tasmania.

NEVILLE

ACTIONS TO PHASE OUT FRASER HOUSE

In a paper called ‘The Therapeutic Community in Rehabilitation of

Drug Dependence’ that Neville delivered at the Pan Pacific Rehabilitation

Conference in 1968, Neville wrote about steps he was taking towards community

mental health. ‘Since September 1965, Fraser House has been innovating a

community psychiatry service for approximately 300,000 population. This

programme aims at intense contact with government public servants, community

aid services and all other relevant community leaders including police,

ministers of religion and all those depended upon by large groups (Yeomans

1968, Vol. 1, p. 267-289).

In a document marked ‘confidential’ called,

‘A Community Developers Thoughts on the Fraser house Crisis’ (Yeomans 1965, Vol.

2, p. 46-48), Neville writes of

actions that would lead to the phasing out of Fraser House.

‘Over the last couple of years the Unit Director and

developer (Dr. Yeomans) has been increasingly involved in strengthening the

organizational preparedness of the outside community, aimed at the relative

devolution of Fraser House and the development of an external therapeutic

(welfare) community’.

This ‘strengthening the organizational

preparedness of the outside community’ was hinted at in the forward to the

second edition of ‘Introducing a Therapeutic Community for New Members’ (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 4).

‘The

major changes in the programs of the Fraser House Therapeutic Community in the

past 20 months (1996) has been the development of an intense Community

Psychiatry Programme, first in Lane Cove municipality in Sept 1965, and more

recently in the Ryde Municipality. The major Therapeutic function of Fraser

House will now be as the center for an intense Regionalized Community

Psychiatric Programme. This programme is aimed at reducing the rates of mental

and social illness in this part of Sydney as a pilot programme and involves a

vast increase in the outward orientation and responsibility of the Unit. Groups

of nurses were allocated localities in the suburbs surrounding Fraser House and

supported patients and outpatients from their areas’.

The Fraser House handbook written by

patients for new staff has a segment on

the Nurses Role:

‘Nurses are assigned in teams to regional areas at the

moment; Lanecove, Ryde, the rest of North Shore, and other areas. Each regional

team is expected to be responsible for knowing its area, its problems and

helping agencies etc. Moreover, nurses in each team are expected to come to

know all in-patients and out-patients of that area; to be specially involved in

the appropriate regional small groups, both in the community and in the Unit;

to record progress notes on their regional patients; to be part of both medical

officer and follow-up committee planning for the patients of their region (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 2, p. 18).’

In September 1965 the Lane Cove

Community Psychiatry Programme began. In June 1966 a similar programme began in

Ryde (Yeomans 1965, Vol 4. p. 2-4).

In discussion with Neville

about Figures 06 and 08 in November 1998 he said that while Fraser House had

been a seminal step, it was still a State run enclave. Kenmore

Therapeutic Community was another State run enclave. Ex-staff member Dr. Madew

was replicating Fraser House at Callan Park.

Neville wanted his ideas

spreading outside of State control. His next step was to move Fraser House Way

out into the community and slowly move community-centered action away from

service delivery and towards grassroots self-help and mutual-help. Neville

spoke of this as, ‘returning wellbeing processes back to grassroots folk’. For

this to happen Neville sensed it was best to let Fraser House be re-absorbed by

mainstream and disappear. He did not want Fraser House remaining as a

government administered service delivery entity that was a mere shadow of how

it was when he was there. Glendon Prison in the UK is a highly successful

prison that is a therapeutic community. Neville said that after having

excellent recidivism rates, way ahead of traditional maximum security prisons

for over thirty years, there has never been any attempt to replicate Glendon

Prison. Neville did not want Fraser House to become an isolated curiosity like

Glendon. Laceweb people generally know little or nothing about Fraser House.

FRASER HOUSE EVALUATION

A cost-benefit analysis designed by Neville revealed the Unit to

be the cheapest and most effective compared to a traditional and to a very new

‘eclectic’ unit. (Yeomans 1980; Yeomans 1980). Treatment results were followed for up to five years and this

research showed that improvement results were maintained (Clark and Yeomans 1969).

Madew, Singer & MacIndoe (Madew, Singer et al. 1966) conducted controlled research in Sydney at Callan House

therapeutic community that was modeled on Fraser House. Coincidently, Professor

Peter Singer was my Behavioral Science (psychology) tutor at La Trobe

University. They found that the therapeutic community was significantly better

at returning patients to the community. The therapeutic community costs were also

significantly lower than the control group.

In 1993, Professor Alfred

Clark published his book, ‘Understanding and Managing Social Conflict’. In this

book Clark specified the 1959-66 ‘Fraser House’ model as being still ‘state of

the art’ as a process for intervening and resolving social conflict within any

context around the Globe (Clark 1993).

FRASER HOUSE A MODEL FOR AMERICAN

RESEARCH

Neville

was delighted to discover that Fraser House was one of the models used in

comparative research by Paul and Lentz in their 1968 research based in

Illinois, USA (Paul

and Lentz 1977, p. 432). Paul and

Lentz used Fraser House as one of their models in developing their milieu

therapy program. However, many of the unique features of Fraser House were not

used by the American researchers. The researchers had also used a ‘poor cousin’

of Fraser House model in their social-learning program as well. The American

researchers used a token economy. Neville set up a small actual economy within Fraser House.

The American

research strongly supported the efficacy of the Fraser House model. Over the

four and a half years of the American research and the next 18 months

follow-up, the psychosocial change programs were significantly ahead of the

hospital group on all measures, with social learning emerging as the treatment

of choice.

While Paul and Lentz’s

clients had been chronic mental patients who had had long-term hospitalization,

with the social-learning group fewer than 3% failed in achieving ‘significant

release’, defined as being longer than 90 days in outside extended-care

facilities. 10.7% of the original social-learning group and 7.1% of the milieu

group were released to independent

functioning, without re-institutionalization. None of the original hospital

group had been released to independent functioning. After four and a half years

of results demonstrating that the two psychosocial programs were clearly

superior to the comparison hospital’.

A cross comparison between structures,

processes, actions and underlying theory within Fraser House and Paul and

Lentz’s psychosocial programs shows that Fraser House contained the aspects

that constituted the effectiveness of both

their milieu and social learning programs. Some of the features of the American

models were present within Fraser House in a more advanced form. Fraser House

also had a large number of potent features that were not present or referred to

by the American researchers. Features of

Fraser House that were neither present in the Paul and Lentz’s American

research nor referred to by the American researchers are listed in Appendix 11 (Paul and Lentz 1977).

The American social learning treatment was

highly structured and very detailed. ‘Today we all learn how to undo buttons

and tie shoe laces.’ The Fraser House

social-learning processes were organically and natural linked into the

community lived life experience of togetherness. The Fraser House process had

patients learning by being responsible for rule making, decision making and

action relating to large sections of community life, via the extensive system

of client run committees and client tasks. The Fraser House model was to have

life teaching them in an individualistic way rather than, ‘all individually

doing the social learning course’, as in the American model.

Heinrichs’ 1984 review

of developments over the previous twenty years in the psychosocial treatment of

long term chronic psychotic patients, identified Paul and Lentz’s research as a

remarkable study, especially it’s outcome of having over 92% of the patients in

the social learning program released, with community stay without

rehospitalisation, for the minimum follow up period of 18 months (Heinrichs

1984).

Heinrichs’ identified another ‘source of great promise’ for psychosocial

strategies. This was the extension of the strategies from the treatment of the

‘patient’ to the treatment of the whole family. Neville had pioneered full

family residential therapeutic community over

twenty years earlier and had family and friends therapy as an integral part

of the sociotherapy of Fraser House since inception in 1959.

ETHICAL

ISSUES IN REPLICATING FRASER HOUSE

It is possible that

psychosocial change may be implemented in incompetent, inappropriate and

unethical ways. Attempts to set up these programs may go seriously astray to

the point where people may be harmed or killed.

We have seen that the

Fraser House Therapeutic Community psychosocial programs were, at various

levels, both simple and complex in their structure and processes. Both highly

specific and very non-specific change actions were used. Many of the structures

and processes were not obvious. Many were very subtle. Incompetent people with

the best intentions in the world may seek to establish psychosocial change

programs. They may operate under a belief in the ‘magical’ quality of the

approaches used - that you set the unit up and ‘let the magic happen’.

The consistent feedback

from all my Fraser House interviewees was that Fraser House was a ‘massive

amount of very tight and difficult work’. As mentioned, in Fraser House

detailed attention was focused on being extremely flexible within extremely

tight psychosocially ecological boundaries. One of these frames was safety at

all levels - physical, emotional, psychosocial, ethical, moral and spiritual.

Meticulous and constant attention was also focused on staff teamwork with

team-building, team-maintenance and teamwork under continual review. The staff

were so dedicated and committed to each other and the community, Neville had to

constantly insist that they go home after their shifts ended instead of staying

on to do things to support. The groundwork laid down by Neville allowed Neville

to be away overseas for nine months with Fraser House thriving in his absence.

Neville was adamant that for any

cloning of Fraser House to be ecological, it would have to grow naturally and

be context and local place dependent; this included how it was embedded within

the local suburbs to ensure the natural evolving of strong functional local

networks. An important issue in replicating Fraser House was that Neville was a

very skilled and very charismatic person and there are few ‘Neville’s around.

As well, as detailed in this thesis, many of Neville’s Ways were not obvious.

One attempt at setting up a

therapeutic community based on the Fraser House psychiatric unit was the Ward

10B unit set up by Dr. John Lindsay at the Townsville General Hospital

Psychiatric Unit (Lindsay

1992). Some

years before, Dr. Lindsay had requested permission to be, and had been an

observer at Fraser House for three weeks. Neville told me in 1992 in Yungaburra

that Lindsay believed that he ‘slavishly’ copied aspects of Fraser House. In

doing this, Neville said that, ‘Lindsay did not allow for the structure of the

city of Townsville’. In Ward 10B there was no evidence of locality or cultural

locality. Neville visited Ward 10B and sensed that Dr. Lindsay had too

faithfully followed Fraser House in a different state, political and

metropolitan context. There was evidence that the Ward 10B staff were far from

being an effective team. After visiting Ward 10B Neville completely dissociated

himself from having anything to do with it. Ward 10B was in no way

encapsulating the Fraser House processes. Following many complaints, Ward 10B

was closed and became the subject of a Royal Commission. Dr. Lindsay gave his

version of events at the Townsville Unit in his book, Ward 10B - The Deadly

Witch-Hunt (Lindsay

1992). Dr.

Mitchell’s Kenmore Therapeutic Community and Dr. Madew’s Callan Park were

successful examples of cloning Fraser House. Dr. Madew was on staff at Fraser

House prior to heading up Callan Park. As mentioned, Neville worked closely

with Dr. Mitchell in setting up Kenmore Therapeutic Community.

REFLECTING

This Chapter commenced with some

criticisms made of Fraser House in the Sixties and responses were given to

these criticisms. Replicating Fraser House in Kenmore and Callan Park Hospitals

was discussed. Material was provided contrasting wider society’s processes for

placing boundaries upon behavior and for accommodating diversity, and Fraser

Houses and the Laceweb’s use of therapeutic community to fulfill the same

functions. The steps taken by Neville to set up transitions to community

self-caring was set out as well as Neville’s actions contributing to the phasing out Fraser

House. Research on Fraser house evaluation was

briefly outlined along with a discussion of American research using Fraser

house as a model. The Chapter concluded with ethical issues in replicating

Fraser House.

Chapter Eight documents

the various outreaches from Fraser House that Neville set up and enabled, and

discusses how these fit into Neville’s frameworks for evolving a social

movement fostering humane epochal transition.

(1963). Kenmore's Group

Therapy Plan - Leading Psychiatrist Visiting Kenmore. Evening Post.

Goulburn.

Clark, A. W. (1993). Understanding

and Managing Social Conflict. Melbourne, Swinburne College Press.

Clark, A. W. and N. T.

Yeomans (1969). Fraser House - Theory, Practice and Evaluation of a

Therapeutic Community. New York, Springer Pub Co.

Coalition of Self Help

Groups (2002). Coalition of Self Help Groups Home page - Internet Source - http://home.vicnet.net.au/~coshg/.

Heinrichs, D. W. (1984).

Recent Developments in the Psychosocial Treatment of Chronic Psychotic

Illnesses T. New York,. The Chronic Mental Patient - Five Years Later.

J. A. Talbott. New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Ireland, R. (1998).

Globalised São Paulo as Invention and Happening: Lessons on a Train. Imagined

Places: The Politics of Making Space. C. Houston, F. Kurasawa and A.

Watson. Melbourne:, La Trobe University.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The

structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The

structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL, University of Chicago

Press.

Lindsay, J. (1992). Ward

10b. Check, Check.

Lindsay, J. S. B. (1992). Ward

10B : The Deadly Witch-hunt. Main Beach, Qld, Wileman.

Madew, L., G. Singer, et

al. (1966). "Treatment and Rehabilitation in the Therapeutic

Community." The Medical Journal of Australia 1: p. 1112-14.

Mitchell, D. N. M. (1964).

The Establishment and Structure of Kenmore Therapeutic Community.

Goulburn, Kenmore Hospital.

Paul, G. L. and R. J.

Lentz (1977). Psychosocial Treatment of Chronic Mental Patients - Milieu

Versus Social-learning Programs. Massachusetts, Harvard University Press.

Yeomans, N. T. (1965).

Collected Papers on Fraser House and Related Healing Gatherings and Festivals -

Mitchell Library Archives, State Library of New South Wales.

Yeomans, N. T. (1968). The

Therapeutic Community in Rehabilitation of Drug Dependence - Paper Presented by

Yeomans, N. T., Coordinator Community Mental Health Dept of Public Health NSW

at the Pan Pacific Rehabilitation Conference. Neville T. Yeomans Collected

Papers 1965, Vol. 1 p. 267 - 283; 283 - 289.

Yeomans, N. T. (1980).

"From the Outback." International Journal of Therapeutic

Communities 1.(1).

Yeomans, N. T. (1980).

From the Outback, International Journal of Therapeutic Communities - Internet

Source - http://www.laceweb.org.au/tcj.htm.