|

Whither Goeth the World - Humanity or Barbarity? The Life Work of Dr. Neville T. Yeomans

Email: lspencre@alphalink.com.au Two

Poems Written by Dr. Neville Thomas Yeomans

The Inma There

seems to be a new spirituality going around - or a philosophy – or is it an

ethical and moral movement, or a feeling? Anyway,

this Inma religion or whatever it is – what does it believe in? It

believes in the coming-together, the inflow of alternative human energy, from

all over the world. It

believes in an ingathering and a nexus of human persons values, feelings,

ideas and actions. Inma

believes in the creativity of this gathering together and this connexion of

persons and values. It

believes that these values are spiritual, moral and ethical, as well as

humane, beautiful, loving and happy. Inma

believes that persons may come and go as they wish, but also it believes that

the values will stay and fertilize its area, and it believes the

nexus will cover the globe. Inma

believes that Earth loves us and that we love Earth. It

believes that from the love and from the creativity will come a new model for

the world of human future. It

believes that we have started that future - now. I

guess that if you and I believe these things we are Inma. On

Where Perhaps somewhere there is an

unimportant place caught between East and West, North and South, Past and

Future. It is so far behind that it can only go

forward. Its indigenous people are so badly

treated they will risk anything for a better life. Its white overlords are so distant

from the center of their own culture that they don’t know where to go except

to Self Government. It is wealthy, industrial, consumer,

under-populated and chaotic. It has tropical coasts and islands. It

has cool mountains and tablelands. It is closer to Asian and Melanesian

peoples than its own capital city, and it often sees itself as the end of the

earth. Yet the desires of some of its

citizens are: to build the first free territory guided by global humane laws to implement the UN covenants on Human Rights to give migrants, visitors and native born an equal say to accept ideas, people and music of living from all over to welcome and respect every interested person to love Planet Earth, and to take a next step towards a happier more beautiful more human

community. Maybe one such place is called

Northern Queensland, Australia. But an Aboriginal word meaning 'a

coming together' is Inma. Together these poems provide a feel for the subject matter of

this Thesis. I first received these two poems at Neville Yeomans’ funeral in

March 2000. CONTENTS

CONTENTS TWO POEMS WRITTEN BY DR. NEVILLE THOMAS YEOMANS CHAPTER ONE - A WARM DECEMBER MORNING AND A DAY IN

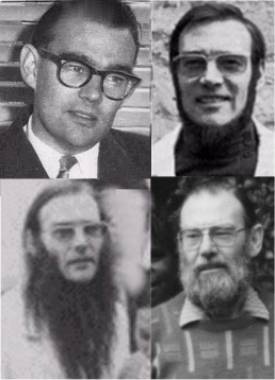

AUTUMN A LITTLE KNOWN EXTRAORDINARY AUSTRALIAN PHOTOS

Photo 1 The Mango Tree out the window of Neville’s

Yungaburra house Photo 2 We sat at this bench as we ate paw paw and

talked. Photo 3 Neville lost in the bush - A painting by L

Spencer. Photo 4 A Photo of Neville in his later years.

Dr.

Neville Thomas Yeomans at his desk at Fraser House - Circa 1961 ACKNOWLEDGING

The research breadth went hand-in-hand

with the support of many. I acknowledge the Indigenous people of Australasia

SE Asia Oceania Region who have been so much a part of the social action at

the heart of this Thesis. I also acknowledge the members of my family who

lived with the myriad small and large consequences of my involvement in this

prolonged and time consuming endeavor. My profound respect for Dr. Neville

Yeomans is woven into this work. My kindred enablers/supporters are integral

- Marj Roberts, Mareja Bin Juda, Norma Perrott, Nasuven Enares and her

sisters Joyce Morris (deceased) and Phyllis Corowa, Faith Bandler, Geoff

Guest, Terry Widders, Alex Dawia, Rob Buschkens, Jules and Chris Collingwood,

John Lonergon and others who know who they are. My other interviewees all had

zest and were so willing - Margaret Cockett, Warwick Bruen, Phil Chilmaid,

Stephanie Yeomans, Stephanie and Ken Yeomans’ Daughters, Allan and Ken

Yeomans, Terry O’Neill, Dr. Ned Iceton, Professor Alfred Clark and the Fraser

House Patient and Outpatient. Financial support at key times was provided by

the Jessie Street Foundation, Down to Earth (Vic) and the Gippsland Catholic

Diocese through Jim Connelly. Stimulating sustained support came from Zuzenka

Kutena, Dr. Elizabeth DeCastro, Judith Goldsworthy, Gregory Leonhart, Dihan

Wijewickrama, Andrew Cramb, Don Foster, Mary and David Cruise, and Dr. Werner

Pelz. Also providing crucial support at key stages were Elsbeth Stephens,

Steve Andreas, Greg Burgess, Richard Clements, Andres Kabel, Barry McQueen,

Richard Maidment, Vic Morrant, and Jim Vickers-Willis. Rich perspectives were

provided by my fellow JCU research students and Dr. Sue McGinty and her

husband Dr. Tony McMahon’s during the Qualitative Research Seminars. Tony as

my supervisor provided sustained caring tight academic support that was

fundamental. I acknowledge the profound connexity of Mother Earth and the Web

of Life source of life Inma - towards a caring humane respectful sustained

Epoch. ABSTRACT

This qualitative

naturalistic inquiry research explores psychiatrist barrister Dr. Neville

Yeomans’ lifelong action towards enabling gentle transitions from the current

non-sustainable inequitable inhumane exploitative Global epoch to a humane

life-affirming one. The research’s three

interconnected areas specify firstly the precursors and structures/processes

used by Yeomans in establishing Australia’s first psychiatric therapeutic

community ‘Fraser House’ in 1959; secondly, Fraser House outreaches; and

thirdly, the evolving of the Laceweb Social Movement through the SE Asia

Oceania Australasia Region. Yeomans ways of social

action are traced to his collaborating with his father P.A. Yeomans and

brothers Allan and Ken in evolving Keyline sustainable agricultural practice

informed by Australasian indigenous people’s experience. The research specifies Dr. Yeomans’ adapting of

indigenous socio-healing/socio-medicine ways and Keyline to the psychosocial

and psychobiological fields in evolving processes he called, ‘Cultural

Keyline’. The

research documents Yeomans’ evolving Fraser House as a dysfunctional fringe

epochal change model – patient self-governance and law/rule making via

patient-based committees, and through this, patients and outpatients

assuming all of the hospital administration roles, including initial

patient assessment, treatment, sanctions, ex-patient domiciliary support,

research, crisis support to the surrounding communities and training

psychiatrists in community psychiatry. Yeomans’ pioneering of Big Group

Therapy (100-180 attending), including all patients and all staff on duty,

and patients’ family/friends/workmates as outpatients is documented. Some of

Yeomans’ leader roles and Big Group/Small Group processes are specified.

Small group therapy with membership based on rotating sociological categories

is described Fraser House outreaches energized by Yeomans are outlined including:

his use of advisory roles to legitimate and protect this social action; his

pioneering role as New South Wales’ first Director of Community Mental Health;

his setting up Australia’s first Community Mental Health Unit in Paddington

NSW; his enabling of the Paddington Festival in 1969 towards starting

Paddington Bazaar to surround this Unit; his energizing of intercultural

festivals, gatherings and artistic happenings in the 1960/70s; his evolving

of intercultural wellbeing networks among Asians and Africans; his adapting

and disseminating of Cultural Keyline to business and other organizations;

his entering as an independent candidate in the 1969 Federal election, his

writing of newspaper columns, his pioneering of mediation in many fields in

Australia, and his contributing to Divorce Law Reform and the inclusion of

family counseling/mediation in Family Law. The evolving of the Laceweb networks amongst Indigenous and

other intercultural healers in the Region supporting self-help/ mutual-help

amongst Indigenous/Small Minorities trauma survivors, and stopping

dysfunction among them is traced to Fraser House and Yeomans’ seminal role in

enabling Aboriginal Human Relations Gatherings in 1971, 1972 and 1973 in

North East New South Wales. Yeomans sustained action research enabling

networking among indigenous/intercultural natural nurturers in the Region are

specified including, his setting up a number of small

Therapeutic Community Houses in Northern Queensland, and extending the Fraser

House model in evolving an International Normative Model Area in Northern

Queensland as a model exploring World Order Governance. The

research concludes with Yeomans’ writings about his macro-framework for

epochal change over the next 200 years, and with future possibilities for the

Laceweb. CHAPTER ONE - A WARM DECEMBER

MORNING AND A DAY IN AUTUMN

The topic of this Thesis, ‘Whither

Goeth The World – Humanity or Barbarity’ entailed researching the history,

theory and practice leading to the evolving of the Laceweb social movement

among Indigenous and intercultural healers through the SE Asia Oceania

Australasia Region This Chapter introduces the life work of Dr. Neville Yeomans,

discusses the significance of the topic, outlines the nature of the research

and the research questions, and discusses why they are important. It also

discusses briefly the story of how I became involved with this project and

the way my biogeography has led me to undertake this research. An outline of

the rest of the Thesis is included. Because of the expansiveness of the

subject, some of the matters that will be treated in some depth in this

research are introduced briefly in this Chapter. This thesis explores Dr. Neville

Yeomans’ role in evolving social action with the aim of enabling a gentle

transition from the current Global epoch to a new humane and life-affirming

one with new forms of social realities respecting and embracing diversity and

having resonance with traditional Indigenous relating to the Web of Life. One

aspect of this change is fostering regionality and locality in a life-world

where every aspect is recognizing, respecting, celebrating, fostering, and

sustaining the inter-connectedness of humane nurturing values and the

diversity of all life forms and networks. The title of the thesis, ‘Whither

Goeth the World – Humanity or Barbarity’ is resonant with Dr. Yeomans’ quest

for Epochal change. This title is an adaptation of a title used by Dr.

Yeomans, ‘Whither Goeth the Law – Humanity or Barbarity’ (Carlson and Yeomans 1975a; Carlson

and Yeomans 1975b) I have elected to use Dr. Neville

Yeomans’ first name in the balance of this Research as a mark of my profound

respect for him. For me he is Neville, not ‘Yeomans’. We had a working

friendship for over 13 years. Neville was of immense support in times of

crisis in my life. A LITTLE KNOWN EXTRAORDINARY

AUSTRALIAN

Dr.

Neville Thomas Yeomans, a little known extraordinary Anglo-Australian

humanitarian was born in 1928 to Percival and Rita Yeomans and died in Brisbane

in May 2000. Neville grew up in a stimulating household. As an adolescent he

worked in sustainable agriculture with his father P. A. Yeomans who was

described by the World famous English agriculturalist Lady Balfour as the

person making the greatest contribution to sustainable agriculture in the

past 200 years (Mulligan

and Hill 2001). Neville Yeomans worked

closely with his father and brother Allan (and later younger brother Ken) in

pioneering a sustainable agriculture process called Keyline (Yeomans

1955; Yeomans 1958; Yeomans 1958; Yeomans 1965; Yeomans 1971; Yeomans 1971;

Yeomans and Yeomans 1993).

Neville adapted Keyline as ‘Cultural Keyline’ and pioneered this in the

fields of psychiatry, sociology of medicine, social psychology,

psychobiology, intercultural studies, peace studies, humanitarian law and

global governance. All of Nevilles and his

father’s work was informed and guided by a relational familiarity with

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wisdom about the social and

natural life worlds. While non-Aboriginal people had seen Australia as a

harsh and hostile place to be conquered and tamed, Aboriginal and Islander

people had a loving and affectionate relation to Earth as their nurturing

mother – a profoundly different relating. Neville encapsulated this relating

in the words of his Inma poem, ‘Inma believes that

Earth loves us and that we love Earth’. Neville and his father’s work

and way were guided and informed by this ancient loving caring tradition. In preparing for his humanitarian

life work, Neville obtained degrees in zoology and then medicine/psychiatry.

He completed postgraduate studies in sociology and psychology with

accompanying extensive reading in history, anthropology and peace studies. He

followed with a degree in law, specializing in humanitarian law, and law

studies in mediation as an alternative to adversarial law in dispute

settlement (Carlson and Yeomans 1975a; Carlson

and Yeomans 1975b). During the 1970s, he studied

spoken and written Chinese and Indonesian, as well as Chinese painting.

Amongst his other studies Neville studied 12 months at the Criminology Law

School at the University of Sydney. As part of his quest to become sensitive

to the intercultural nuances of the Region, Neville studied at a Technical

College for eighteen months in Indonesian language and twelve months in

Mandarin language both as spoken and written languages. He remained an avid reader and engaged in continuous

action research throughout his life. Neville commenced his endeavors with what he called the ‘mad and

bad’ people of Sydney. Neville said that he recognized that in 1959, with

considerable upheaval and questioning in the area of mental health in NSW,

and a Royal Commission being mooted into past practices, there was a small

window of opportunity for innovation. Neville started his epochal quest in

earnest by setting up the psychiatric unit, Fraser House, in the grounds of

the North Ryde Psychiatric Hospital in 1959. He obtained permission to have

half of the patient intake from prisons so that he could explore self-help

possibilities among the ‘mad and bad’ at the fringe of society. In

psychiatry, Neville was a World leader in therapeutic community, full family

therapeutic community, community mental health, and large group therapy. Many

of the iconoclastic practices that he introduced into psychiatry are now

standard practice in Australia. He pioneered suicide support and other life

crisis telephone services, the running of multicultural community markets and

festivals and other multicultural events, and alternative lifestyle

festivals. Neville also influenced the introduction of family counseling and

family mediation into family law in Australia and mediation into Australian

society. He was also responsible for energizing praxis networks in such

diverse, though related fields as social work, criminology, family

counseling, community services, community mental health, prison

administration, business management, intercultural relations, psychosocial

self-help groups, social ecology, futures studies, self organizing systems,

qualitative method, World order, and Global, Regional, and Local Governance. While the many things Neville

Yeomans pioneered are now known by many in Australia and around the World,

very few know he was the initiator. The (Sydney) Sun newspaper included

Neville’s groundbreaking work in psychiatry and therapeutic community with

six other Australians under the heading, ‘The Big Seven Secrets Australians

were first to solve’ (17 July, 1963). Dr. Neville Yeomans was included

with people like Sir John Eccles, Sir Norman Greg and Dr. V. M

Coppleson. How

all these diverse social actions are related and interlinked by Dr. Neville

Yeomans and others are the foci of this Thesis This research traces

Neville Yeomans fostering of the emergence of a social movement he called the

Laceweb evolving amongst oppressed Indigenous and Small Minorities in the SE Asia

Oceania Australasian Region. Wellbeing

action by Indigenous, Small Minority and intercultural psychosocial healers

and natural nurturers has been evolving in the Region for over 40 years. This

network of ‘natural nurturers’ continues to evolve. Some of the focal people

now engaged in the Laceweb movement that emerged from Neville’s Sydney action

are among the most oppressed and marginalized people in Far North Queensland

and around the Darwin Top End. They are Aboriginal and Islanders and other

people such as East Timorese, West Papuans, Bougainvillians and others from

oppressed minority groups in the Region with small populations. Global

governance organizations call them ‘Small Minorities’. These focal people are

mainly women. Neville’s term for these informal networkers was ‘natural

nurturers’ as they are engaged in self-help and mutual help as they go about

their everyday lives. The research explores

Neville’s claim that he was actioning a three hundred year-plus project -

Laceweb action evolving humane transition processes towards a more humane

caring nurturing epoch; one that respects the Earth and all life on it. This research traces the

evolving of Laceweb networks in the Region supporting

self-help and mutual-help amongst Indigenous and Small Minorities’ trauma survivors,

as well as supporting the resolving of domestic violence, oppression of women

and children, sexual abuse, substance abuse, criminal and psychiatric

incarceration, and other dysfunction towards evolving a humane caring

nurturing Way of life as exemplars of Epochal change. Neville had first hand

experience of this dysfunction in growing up near remote aboriginal

communities. At the same time he recognized that indigenous holistic communal

process sustaining social cohesion had potency in resolving the above

dysfunction - what Neville called

Cultural Healing Action. THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS

While aspects of this endeavor have

been the subject of a PhD (Clark 1969), and other research and writings in

the past (Yeomans 1961; Yeomans 1961; Webb

and Bruen 1968; Clark and Yeomans 1969; Watson 1970, p 109; Paul and Lentz

1977; Yeomans 1980, p.64; Yeomans 1980; Wilson 1990, Ch 6, p. 71-85; Clark

1993, p. 61, 117) this will be the first research

that attempts to draw the many aspects of the above and related social action

together. It took a number of months

of reflection and discussions with Neville and my Supervisor for three

‘natural’ parts to emerge - Fraser House, Fraser House outreach and the

evolving of the Laceweb. The research questions emerged from this cleavering. The research questions are: 1. What were the theoretical

and action precursors to, and the nature of the structuring and processes

used by Neville Yeomans in evolving and sustaining the psychiatric unit

Fraser House? 2. What change processes,

innovations and social action evolved in and from Fraser House? With what

effect? 3. What is the Laceweb? What is

its structure and process, and how has it being evolving and sustained? 4. What patterns and

integration are there linking aspects of Neville Yeomans’ work - Fraser

House, Fraser House outreach and the Laceweb? 5. What possible futures may

emerge from Laceweb praxis As the Thesis is investigating

something with so many facets, I had to make decisions about my research

focus and what was to be included and excluded. I have elected to report

extensively on structure, process and their connexity while providing a broad

feel for their fit in the interstices of Neville’s massive endeavor. In order

to cope with the extent and complex richness of my focal interests, the

following are excluded. Firstly, while outlining and

answering the criticisms others have made about Neville and Fraser House, I

do not engage in identifying shortcomings, or criticizing his life work. I

have gathered together material that others may use for further research

including critique and evaluation. The limits I set to my research have still

left me with a massive endeavor. Secondly, I

report on Neville’s extensive life work and public persona and the public life

of Fraser House staff. I exclude research concerning his personal life while

acknowledging and recognizing this was and is fundamental to an understanding

of the man. In fact, Neville recognized and made restricted file notes on

issues in his and other Fraser House senior staff’s private lives that were

reflected in the dynamics of Fraser House. Neville drew attention to the

ethical dilemmas in research where adequate writing up of a case would give

sufficient material to identify focal people to their potential harm. Neville

made suggestions in a short monograph to the World Health Organization that

may address these dilemmas about research protocols including anonyminity of

individuals, institutions and nations where important, though social delicate

research, is being conducted (Yeomans 1965, Vol. 12, p. 129-130). Thirdly, while researching the

evolving and the nature of the Laceweb social movement, the Laceweb networks themselves

have not been researched. I have scant links to these networks and I am not

cleared to share information. Fourthly, while the social action

being researched has drawn on Australian and Oceania Indigenous

socio-medicine and other social and community social cohesion knowledge and

way, this thesis only briefly describes some of these without going into

detail. I do not re-present or speak for anyone. LIFE CHANGES

I was

privileged to be mentored by Neville over a fourteen-year period from 1986 to

2000. Neville arranged for me to engage in sustained action research into every

aspect of his life work. I researched and wrote this Thesis with his

blessing, encouragement, cooperation and support. Further, I carried out this

research so that Australians and the World would know more about this man.

With the inhumane self serving behavior of sections of the World traumatizing

and exploiting/harming the majority of the Earth’s population and fast

destroying our children’s’ future, Neville’s lifework is timely, practical,

seminal and potent. This Thesis makes his life work accessible. I first met Neville in the mid 1980’s. At first all I knew about

him was that he was a psychiatrist who had just come back from doing a really

interesting workshop on powerful brief therapeutic processes – NLP Sensory

Submodality Processes (Bandler, Andreas et al. 1985; Andreas and Andreas

1987). At

the time I knew nothing of Fraser House or Neville’s wider work. I attended

the workshop he was co-facilitating in Balmain, Sydney. I was taken with the

ecology of the man. He was precise and thorough, and incredible quick in

sensing everyone in the group. I had never met anyone like him. He singled me

out as a resonant person. At lunch on both days of the workshop we shared

life stories related to working with groups and change processes. He

specifically engaged me on my academic and work experience. By the end of

that lunch, he knew I had a Social Science degree in Sociology and a

Behavioral Science Honors Degree in Psychology. My honors research was in

clinical psychology and I had completed postgraduate studies in

neuro-psychology. He knew I had been eligible to do PhD level research since

1981. He also knew of, and could see ‘fit’ in my prior degree-level industry

studies in actuarial and financial services to become a Fellow of the

Australian Insurance Institute by examination. He also saw resonance in my

Diploma level studies in Personnel Management and Organizational Training and

Development. I was for a time a member of the Australian Institute of

Personnel Management and the Australian Institute of Training and

Development. Neville delighted in my revelation that I had been sacked from

most of my jobs for provoking the system to change; at the time I did not know

that Neville worked with the resources on the margins. At that first meeting

I had no idea that Neville was a constant networker and that he was checking

me out as to how I might fit and be interested in the social action he was

engaged in. We discussed my consulting work supporting CEOs of multinational

companies on organizational change, and psychosocial group process at the

senior executive level. I found out later that he had seen ‘fit’ in all

aspects of my background including my security consulting work in electronic

article surveillance. I had my training in counseling from Terry O’Neill at the

Student Counseling Unit at La Trobe University in the late 1970’s and was an

on-call para-professional crisis counselor in the La Trobe University Student

Counseling Center for eighteen months. I found out shortly after meeting

Neville that Terry based his way of counseling largely on Terry’s voluntary

work at Fraser House and the influence of Neville in the 1960’s. When I told Neville about Terry training me

in counseling this further strengthened his interest in me as a potential

resource. Because of my psychosocial community and group therapy

experience, much of it subsequently in groups with Neville, and my brief

therapy skills, Neville arranged for me to provide 18 months in-service

training and mentoring support to a psychologist friend of his working within

a medium security special protection prison facility. This involved my

co-facilitating, along with the jail psychologist, groups of 12 inmates as

well as mentoring the jail psychologist on one-on-one work. Neville

specifically broached my potential to research his lifework via a PhD in

1992. Key things for Neville were that

I was eligible to do a PhD and also, that I had experienced major trauma in

my life. I knew from personal experience about trauma self-help. In

Queensland in 1993 he again went thoroughly into all my background although

the chatting was laid back. Little did I know then how my entire blend of

background ‘fitted’ his interests and foci. It seems that I was potentially

the person he had been looking for for more than 20 years (Yeomans 1980; Yeomans 1980, p. 64; Yeomans 1980). He quietly suggested me doing a PhD on his life work a number

of times in the following years. By 1997, he was keen for me to get started as he knew he was in real

trouble with his health and that it was life threatening. When I told him in

July 1998 that I was starting a PhD on his life he was elated. I could

literally see his mind clicking. He was checking for fit. Then he said a big,‘Yes! Your background is

perfect!’ I knew in large part this was because of my dysfunctionality as

well as my experience and abilities. As discussed throughout this research,

Neville had great faith in the dysfunctional fringe. A WARM DECEMBER MORNING

This thesis is about people connecting with each other and

discovering and learning from and supporting each other. I will share a few

things that may support you in connecting with the pith and moment of this

research and how I came to be doing it. Neville Yeomans and I are eating paw

paw in Yungaburra. It is a warm December morning in 1993 – in the lush

greenness of the tropics of Far North Queensland, Australia. Neville and I

are having a good time in friendly banter. Through the open window of

Neville’s heritage listed large bungalow type house comes the sweet smell of

hundreds of over-ripe mangoes on an immense tree. The air is permeated with the fragrance of frangipani and other

tropical flowers. Going back there in memory now, my longtime friend and

colleague and I are engaged in a casual conversation of significance. We are

talking about the origins of the passions that have energized and interwoven

our lives. Neville has no hesitation in saying that a defining moment in the

origins of his passions occurred in 1931 when he was three years old. He

recalls becoming separated from his parents and being lost in the hot arid

desert of Western Queensland.

Photo 1 The Mango Tree out the window of

Neville’s Yungaburra house

Photo 2 We sat at this bench as we ate paw

paw and talked.

Photo 3 Neville lost in the bush - A

painting by L Spencer. In wandering away from his parents as a three year old, Neville had

been absorbed in minutia - looking at the little plants and pebbles. After a

time his body demanded his attention away from the pebbles. He was becoming

parched. His mouth and lips were becoming very dry. His attention flits again

to the pebbles. Then everything begins to shimmer. Every direction seems the

same. His legs go to jelly and the world begins to tilt all over the place as

he crashes to the ground from heat exhaustion. Neville vividly remembers his

near death delirium. Being a bright little three year old, he knows about

death and that he is about to die. He desperately longs to live to make the

world a better place. In delirium, emotions sweep him. Awful dread mingles

with immense love - and all this is reaching out for love and nurturing and all their possibilities. In his

near-death delirium little Neville sees a shimmering black giant coming

towards him and feels being gently picked up. Neville feels the giant’s

gentleness - strong yet soft - and presently he feels the cool fresh water

that gently touches his lips, and is being poured on his body, and assuaging

his raging thirst. Then, still in delirium, Neville feels being carried for a

time and then passed by the Aboriginal tracker who had found him to nurturing

Aboriginal women and he is ‘home’ again and his yearning is being

full-filled. The above piece was confirmed by Neville in September 1998 as

encapsulating the feel of his experience. It was part of my first writing

that reduced Neville to tears. Neville, in the care of these Aboriginal women had personal

experience of Aboriginal socio-medicine. He knew from his own experiencing of

it that Aboriginal socio-medicine is powerful. Psychiatrist Richard Cawte has

written of Aboriginal socio-medicine (Cawte 1974; Cawte 2001). I understand Indigenous socio-medicine to entail a wide range

of social processes with a central aim of community social cohesion and

wellbeing. Aboriginal socio-medicine links the psychosocial with the

psychobiological through special forms of embodied social interaction.

Neville experienced and embodied this link. Neville spoke of how, during the

years of his childhood, he constantly returned to his desert delirium

experience as he was forming his very big dream of doing things that would

make the World profoundly different. The dreaming evolved as an action quest.

Neville said that from that traumatic experience, what he was

exploring and mulling over all the time as a child and later as an

adolescent, was how could he enable an Epochal transition. He was talking of

enabling a shift of the magnitude of the one from the Feudal System to the

Industrial System in England. He read up on how that transition occurred. He

was passionate about how he could link with others in enabling a Global

Epochal transition to a humane, nurturing, sustainable social-life-world. He

was talking about a life-world that is respecting, celebrating and sustaining

diversity of all life forms and networks on the biosphere. He kept asking

himself, how would someone do that? How could he do that? He realized that it

may take up to 300 years to do. And if it takes a few life times to do this,

what could he do that would set up action that was self-energizing and

self-organizing; processes that could, no - would withstand the withering ways of the current epoch in

decline as it seeks by any means to maintain itself. What processes could

enable reconstituting to continue through time, to finish the transition? Even on hearing Neville saying words like these in 1993, it

never occurred to me that that was what he was really attempting to do. Subsequently, a number of people I

interviewed about Neville all confirmed the epochal focus of his social

action. Margaret Cockett, his personal Assistant at and after Fraser House,

Stephanie Yeomans, his Sister-in-law, and Stuart Hill, a Professor of Social

Ecology at University of Western Sydney, all said that Neville had said

similar things to the above in talking with them about the emergence of his

quest from his childhood sociomedicine experience. As well, Paul Wilson, who

was for a time Head of the Australian Institute of Criminology and now Dean

of the School of Humanities at Bond University, implies the same

understanding of Neville’s quest in his writing (Wilson 1990, Ch. 6). Neville went on to tell me a story that was similar to his being

lost in the bush. In 1943, Neville’s father co-purchased with his brother-in-law

Jim Barnes, two adjacent properties totaling 1000 acres at North Richmond,

one hour West of Sydney in NSW (Mulligan and Hill 2001; Hill 2002; Hill 2002). In the next year when Neville was sixteen, a second defining

episode occurred. Neville was out riding on his horse Ginger on one of their

properties with his Uncle Jim (Barnes) when they were caught in a grassfire

that was being fanned by powerful winds. Jim yelled to Neville to dismount

and squeeze into the hollow of a dead tree and cover himself to shield the

radiant heat. The firestorm was coming towards them at phenomenal speed. The

fire front was long. Jim on his horse could neither outflank it nor out-race

it. Being too large to squeeze through the gap into the stump, Jim rode

straight at the fire – attempting to ride through it. The horse went from

under him, and Neville, watching from within the tree stump saw his Uncle

burn to death. Amid the shock and horror was the dread of his own impending

horrible death. Neville said that he slumped into traumatized delirium consumed

with dread laced with pervasive love similar to his experience when lost as a

three year old. He described being on the edge of oblivion and again yearning

for a better reality for all people. When found, physically safe, Neville was

profoundly traumatized. Ginger, though singed, survived. Circumstance created another similarity. At age three it was the

Aboriginal women who gave nurturing care. During the time of this grass fire

there happened to be an Islander women staying with the Yeomans family as a

housekeeper-support for Neville’s mother. The woman was an Australian South

Sea Islander - Faith Bandler’s sister, Kathleen Mussing. It was in Kathleen’s

nurturing care that Neville found enfolding love. Faith Bandler was one of

those responsible for the referendum on Aboriginal voting rights. Faith had

support from Jessie Street. The Jessie Street Foundation in memory of Jessie

has supported Laceweb action in 2001 and 2002 (Laceweb-Homepage 2001). Neville attributed his healing from this second trauma in the months

following the fire, to the nurturing socio-medicine of this housekeeper,

Kathleen. In essence, this entailed love, care, nurturing and affection as

the central components of psychobiological healing. Neville re-met Kathleen Mussing when she

was old and dying and she didn’t recognize him. Neville described that

meeting as one of the saddest experiences in his life, though permeated for

him with immense love. In the ensuing years up till the Yungaburra 1993 conversation,

Neville had progressively involved me in aspects of his quest. Even so, I

knew very little. It was a bit at a time. I did not know at the time that he

had written a letter to the International Journal of Therapeutic Communities

in 1980 providing an overview of his work (Yeomans 1980, p. 64; Yeomans 1980). This short letter is reproduced in full below: From the Outback Dear Sir, Since A. W.

Clark and I produced the monograph ‘Fraser House’ in 1969, I have moved to

private practice in Cairns, North East Australia. This is an isolated area

for this country, but is rapidly becoming an intercultural front door to

Melanesia and Asia. ‘Up North’

the therapeutic community model has extended into humanitarian mutual help

for social change. Two of the small cities in this region have self-help

houses based on Fraser House. An Aboriginal Alcohol and Drug hostel is moving

in the same direction, as are other bodies. These are

facilitated by a network called UN-Inma, the second word of which is

aboriginal for Oneness. Actually, aborigines have discussed offering one of

the Palm Island group off the North Queensland coast as a model therapeutic

community prison. The Director

of the Australian Institute of Criminology has the support of the United

Nations Secretary-General for the idea of an international island haven for

otherwised condemned political prisoners. Our proposal is an application and

extension, in which the Institute Director is ‘extremely interested’. The main

conditions sought by the Indigenous group are that selected aborigines in

Australian prisons also be permitted to complete their sentences on such

islands; and that therapeutic self-management with conjugal rights be the

administrative model. One of our major next

steps is to bring together a psychosocial evaluative research team to monitor

the development of this regional community movement. Such may take some time

as social scientists are fairly uncommon in the area (my italics). Some years ago, I arranged a cost-benefit analysis of Fraser

House, compared first with a traditional Admission unit in another

psychiatric hospital, and second with a newly constructed Admission unit

which some felt might be a pseudo therapeutic community. Somewhat to my surprise Fraser House was not only more effective

but also cost less than the other two. The traditional unit was next

cost-effective and the ‘pseudo’ unit least. Unfortunately this report was

never publically circulated. Until recently I was unable to locate a copy.

One has now been found and it seems I may soon have a manuscript. This Thesis revisits this letter in documenting the flow-on

action from Fraser House. Note the italicized paragraph. Neville had been

looking for someone like me at least from 1980. He was sizing me up in the

mid 1980s. AN AUTUMN DAY

During September 1998 Neville agreed to read some of my Thesis

writing about the precursors to Fraser House. Neville said, ‘When I read your

draft it was so congruent, it moved me to tears - it’s like a scientific

detective story.’ My writing touched strong emotions that had him sobbing. He said

I was underway and that he would not comment more on that piece of writing or

read any of the Thesis until it was finished so that it was my work,

self organized by me. In November 1999, Neville asked whether I would have

the Thesis finished by February 2000. He was very keen to read it, though

only when it was finished. When I told him it would not be finished by then

he said that was regrettable. In December 1999 there was inexplicably no

reply on his phone for two and a half weeks. Then one morning Neville’s

daughter answered the phone and said that Neville’s bladder cancer, which had

been in remission, had rapidly moved everywhere in his body and that he would

die very soon and that they were shifting him from hospital to his former

wife (his second wife) Lien’s place in Queensland. His daughter said he was

so bad I would not be able to speak to him again. This was devastating news.

I rang the hospital for a status report and was knocked further emotionally

to be put directly though to Neville without knowing this was about to

happen. Neville spoke and sounded the best I had every found him. He was

clear, calm, relaxed, poised and centered. He said, ‘Les have you heard. The

cancer’s gone everywhere. I have just received a massive dose of morphine and

I am going up to be with Lien (his second Wife) and Quan (his son). I can’t

help you any more. Goodbye’. I said, ‘Goodbye.’ Those seconds were our last

chat. Then he hung up. Quan said in April 2000, ‘If Neville died this instant

it would be a mercy’. He died about 4 weeks later in May 2000. Neville’s

Obituary written by a friend Peter Carroll was read by Carroll at the funeral

and appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald. It is included as Appendix 1.

Photo 4 A Photo of Neville in his later

years. THE

THESIS STRUCTURE

While arbitrary, this Thesis divides

Neville’ life work into three inter-woven threads. The first part is

Neville’s pioneering in Australia of community therapy and his global

pioneering of full-family residential therapeutic community practices within

the therapeutic community based psychiatric unit, Fraser House (Yeomans 1961, p.382-384; Yeomans

1961, p.829-830). Neville set up this Unit at North

Ryde Psychiatric hospital on the North Shore in Sydney, NSW in 1959, and

became its founding director and psychiatrist. Neville and other Fraser House staff

claimed that Fraser House practice established that extremely dysfunctional

people could be the prime source of their own reintegration and move to

wellbeing functioning (Yeomans 1961; Yeomans 1961; Madew,

Singer et al. 1966; Clark 1969; Clark and Yeomans 1969). The precursors influencing Neville

in setting up and evolving Fraser House are explored. A core and integrating

aspect of the Thesis will be articulating the emergence and the use of a way

of being, functioning and action by Neville’s father, P. A. Yeomans in

creating Keyline processes in sustainable agriculture. Neville’s extended his

father’s Keyline into the psychosocial sphere within Fraser House and Fraser

House outreach in a process Neville called Cultural Keyline. This is

researched Another thread woven through

Neville’s life and this Thesis is the wisdom and being of Indigenous people. P.A.

(Neville’s father) and Neville had a lot of contact and affinity with

Australian Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea

Islander people. Neville particularly sought out the company of nurturing women

from these groups. The father and son’s profound connexity to nature is

resonant with Indigenous way. ‘Connexity’ is an old English word meaning that

a connexion continues between people, things, and between people and things

such that they are simultaneously interwoven, inter-dependent,

inter-connected, inter-related, and interlinked. Neville’s pioneering of both

therapeutic community and full family therapeutic community in Australia are

documented. In the second part of the Thesis,

the research documents the spread and influence of Fraser House’s guiding

frames of reference, structure, processes and practices into the wider

community. The claims by Neville and other Ex Fraser House staff that Fraser

House’s structure, processes and practices had a substantial effect on mental

health practice in Australia are investigated. The third part of the Thesis traces

the use by Neville of Fraser House’s frames of reference, structures,

processes, practices and outreach in enabling the evolving of the Laceweb

Social Movement spreading among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

and other minorities in the remote regions of Far North Australia and

extending throughout the SE Asia Oceania Australasia Region. In enabling with

others this network, Neville was tapping into pre-existing nurturing energy

amongst Indigenous people and people of oppressed small minorities in the

Region. The Thesis traces the processes used to extend this social movement

via networking among people Neville described as, ‘natural nurturers’. While

these people are typically fighting for their very existence as a people and

culture in their place, Neville said that the natural nurturers were always

present and have been present since antiquity. Neville

and others fully recognized that everything they did was using and/or

re-constituting the socio-cohesive ways of being of the ages among focal

people who had been decimated by dominant societies. The Research documents

the psychosocial and other histories of Laceweb social action over the past

forty-three years, as well as their precursors from the 1930’s onwards. The term ‘Laceweb’ was initiated by

Neville. One summer morning in 1993 in Yungaburra in Far North Queensland,

Neville and I were discussing the Laceweb and it seemed that the Movement

had, as far as Neville knew, no name. Neville knew the potency of symbols,

icons and logos and said these were not used in the Laceweb, and he did not

think them in any way appropriate at the present. Neville talked about naming

the movement. Within seconds he came up with ‘Laceweb’. This name was, in

Neville’s terms, ‘an isomorphic metaphor’ – something of similar form and

resonance to the social movement that was evolving. The name was from a

natural outback Australian phenomenon that Neville had personally

experienced. Some years previously Neville had been traveling alone in

outback Queensland. When he awoke in the morning and looked out of his tent,

the low gorse bush, about fifty centimeters high, appeared to be covered in

snow as far as the eye could see. What had happened was that during the night

millions of tiny spiders had floated in on thin webs, drifting in the slight

moving air. The continuous, immense web the spiders had spun overnight

stretched to the horizon in all directions. For Neville it had a very Yin –

very feminine energy reminiscent of lace, and hence ‘Laceweb’. The many ways

that this metaphor is resonant with the Laceweb Social Movement is discussed

in Chapters Nine and Ten. The Thesis Chapters are as follows. Chapter

Two discusses the method used in completing this Thesis, including processes

used in data collection and analysis. It also identifies and gives brief

backgrounds of the people interviewed. Chapter Three describes the frames and ways used by Neville, and

the influences on his Way, including Keyline, Indigenous wisdom and way,

specific life experiences, academic study and reading, as well as his

theoretical and pre-theoretical reflecting. Another

resonant conceptual link for Neville was the Chinese Yin/Yang concepts with

difference/diversity and unity as aspects, with humane healing nurturing

being very much part of the Yin nature. Neville was always exploring the Yin

energies and how they may temper Yang energies. Chapter Four outlines Fraser

House’s structure and processes, while Chapter Five discusses Fraser House

change processes. Chapter Six explores Neville’s use of Cultural Keyline in

enabling change in both psychosocial and psychobiological systems

simultaneously. Chapter Seven explores

criticisms of Neville and Fraser House as well as the steps taken by Neville

to set up transitions from government and private sector service delivery to

community self-caring. Fraser house evaluation is briefly outlined along with

a discussion of American research using Fraser house as a model. The Chapter

concludes with ethical issues in replicating Fraser House. Chapter Eight discusses the

extensions of Fraser House into the wider community and their implications.

Chapter Nine explores the nature, the evolving, and the history of the

Laceweb and its potential. Chapter Ten is integrative. It introduces

Neville’s 300 year model of epochal transition and provides glimpses of

future possibilities for Laceweb praxis in every aspect of the social life

World. REFLECTING

This Chapter has introduced the

topic, the history, theory and practice leading to the evolving of a social

movement known as the Laceweb. It has briefly discussed the significance of

the topic, outlined the nature of the research and the research questions, and

why they are important. It has explored how I became involved in the project

and the way my biography has led me to undertake the research. The next

Chapter discusses the research methods used in this Thesis. REFERENCES

(1963).

The Seven Big Secrets Australians were First to Solve. The Sun. Sydney:

p. 28. Andreas, C. and S. Andreas (1987). Change

Your Brain and Keep the Change - Advanced NLP Submodalities Interventions.

Boulder, Colorado, Real People Press. Bandler, R., S. Andreas, et al.

(1985). Using your brain--for a change. Moab, Utah, Real People Press. Carlson, J. and N. Yeomans (1975a). Whither

Goeth the Law - Humanity or Barbarity. Melbourne, Lansdowne Press. Carlson, J. and N. T. Yeomans (1975b).

Whither Goeth the Law - Humanity or Barbarity -. The Way Out - Radical

Alternatives in Australia - Internet site - http://www.laceweb.org.au/whi.htm.

M. C. Smith, D. Melbourne, Lansdowne Press. Carlson, J. and N. T. Yeomans (1975b).

Whither Goeth the Law - Humanity or Barbarity - http://www.laceweb.org.au/whi.htm.

The Way Out - Radical Alternatives in Australia. M. C. Smith, D.

Melbourne, Lansdowne Press. Cawte, A. (1974). Medicine is the

Law - Studies in Psychiatric Anthropology of Australian Tribal Societies.

Adelaide, Rigby. Cawte, J. (2001). Healers of Arnhem

Land. Marleston, SA, J.B. Books. Clark, A. W. (1969). Theory and

Evaluation of a Therapeutic Community - Fraser House. University of NSW

PhD Dissertation. Sydney. Clark, A. W. (1993). Understanding

and Managing Social Conflict. Melbourne, Swinburne College Press. Clark, A. W. and N. T. Yeomans (1969).

Fraser House - Theory, Practice and Evaluation of a Therapeutic Community.

New York, Springer Pub Co. Hill, S. B. (2002). Redesign As Deep

Industrial Ecology: Lessons From Ecological Agriculture And Social Ecology. Hill, S. B. (2002). 'Redesign' for

Soil, Habitat and Biodiversity Conservation: Lessons from Ecological

Agriculture and Social Ecology. Laceweb-Homepage (2001). Second SE

Asia Oceania Australasia Trauma Survivors Support Network Healing Sharing

Gatherings - July 2001 - Internet Source - http://www.laceweb.org.au/indexA.htm. Madew, L., G. Singer, et al. (1966).

"Treatment and Rehabilitation in the Therapeutic Community." The

Medical Journal of Australia 1: p. 1112-14. Mulligan, M. and S. Hill (2001). Thinking

like an Ecosystem - Ecological Pioneers. A Social History of Australian

Ecological Thought and Action. Melbourne, Vic, Cambridge University

Press. Paul, G. L. and R. J. Lentz (1977). Psychosocial

Treatment of Chronic Mental Patients - Milieu Versus Social-learning

Programs. Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. Watson, J. P. (1970). "The First

Australian Therapeutic Community - Fraser House." British Journal of

Psychiatry. Vol. 117. Webb, R. A. J. and W. J. Bruen (1968).

"Multiple Child Parent Therapy in a Family Therapeutic Community." The

International Journal of Social Psychiatry Vol XIV, No. 1. Wilson, P. (1990). A Life of Crime.

Newham, Victoria, Scribe. Yeomans, K. B. and P. A. Yeomans

(1993). Water for every farm : Yeomans Keyline plan. Southport, Qld.,

Keyline Designs. Yeomans, N. T. (1961). "Notes on

a Therapeutic Community Part 1 Preliminary Report." Medical Journal

of Australia Vol 48 (2). Yeomans, N. T. (1961). "Notes on

a Therapeutic Community Part 2." Medical Journal of Australia Vol

48 (2). Yeomans, N. T. (1965). Collected

Papers on Fraser House and Related Healing Gatherings and Festivals -

Mitchell Library Archives, State Library of New South Wales. Yeomans, N. T. (1980). "From the

Outback." International Journal of Therapeutic Communities 1.(1). Yeomans, N. T. (1980). From the

Outback, International Journal of Therapeutic Communities - Internet Source -

http://www.laceweb.org.au/tcj.htm. Yeomans, N. T. (1980). "From the

Outback - http://www.laceweb.org.au/tcj.htm."

International Journal of Therapeutic Communities 1 (1): 64. Yeomans, P. A. (1955). The Keyline

Plan, Yeoman's Publishing. Yeomans, P. A. (1958). The

Challenge of Landscape : the Development and Practice of Keyline. Sydney,

Keyline Publishing. Yeomans, P. A. (1958). The Challenge

of Landscape: The Development and Practice of Keyline. - Internet Source - http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/01aglibwelcome.html. Yeomans, P. A. (1965). Water for Every

Farm - Internet Source - http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/01aglibwelcome.html. Yeomans, P. A. (1971). The City

Forest : the Keyline Plan for the Human Environment Revolution. Sydney,

Keyline. Yeomans, P. A. (1971). The City

Forest: The Keyline Plan for the Human Environment Revolution. Internet

Source - http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/01aglibwelcome.html. |

|

|